Before we begin, I should note that despite my post last week, life is not always sunshine and big fish for the Osprey of Missoula.

Anyway, on to this book. I have to admit, I normally have a twinge when I see the phrase “backyard birds.” Not because there’s anything wrong with common or confiding species, but because depending on where you live and what you do with your habitat, darn near anything can be a backyard bird. Here in Montana I use an expansive definition of “yard” to put Barrow’s Goldeneye on my yard-list. There’s a house I’ve long dreamed of perched next to Jamaica Bay that has Curlew Sandpiper and Ruff as possibilities, with a good enough scope; heck, a flock of Wood Storks once flew over the very average suburban Atlanta back yard of the Inimitable Todd’s very average brother and sister-in-law and thus got on my life list. But you will never see any of these in the standard guide to backyard birds.

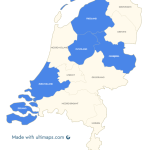

My “yard” is seen above.

Backyard Birds: Looking Through the Glass is different. It pays tribute, not to the general idea of backyard birds, but to the specific birds in a specific backyard in Ohio, each photographed through a window of the author’s home. (The copyright page even contains the heartening disclaimer that “no birds were touched or disturbed for any of these photographs” — something that would be welcome on the pages of many outdoor magazines.)

As such, “backyard birds” is no longer a phrase of meaningless generality, but a paean to patch birding, to careful observation, to the author’s conversion from a globe-hopping pursuer of the exotic to a lover of the wonders found quietly at home. A Rose-breasted Grosbeak, here, is an exciting one-off visitor, and a wonderful shot of Mourning Doves in the act of mating is the equivalent of half an hour of Animal Planet.

Author Glen Apseloff deserves credit not only for selecting an excellent premise, but for fine photography skills (and great diligence in keeping his windows clean) and for maintaining feeders that draw a wide variety of species, including relatively shy ones like Scarlet Tanager and Brown Thrasher. He also includes a fun, if brief, section dedicated to the non-avians (butterflies and mammals, in this case) that he has photographed through his windows.

Taking pictures through windows is not easy.

The text is not destined to set the literary world aflame (transitions from one species account to the next, in particular, tend to be bumpy and repetitive) and it sometimes appears a bit crammed in between the photos, but it is rich with information and personal narrative of the author’s encounters with new species, as well as helpful though basic advice about photography techniques and habitat improvement. Anyway, the words are supporting matter here. The photographs are the stars, and as such the birds are the stars, each one wearing the label “backyard bird”, here, with meaning and pride.

I totally agree with your misgivings about the term “backyard birds”, Carrie. As I love to tell beginning birders in the northeast, my backyard list for my sister’s backyard, in Florida, includes Limpkin, Ring-necked Duck, and Pied-billed Grebe. “Feeder birds” is a more accurate term, I think. But, maybe not such a good book title.