There is GISS and there is Birding by Impression and they are not the same. GISS—general impression, size, shape—is intuitive, the result of an unconscious cognitive process derived from experience in the field. Birding by Impression is a conscious, deliberate method of identifying and recognizing birds based on the study and evaluation of “distinctive structural features and behavioral movements” and comparison with nearby and similar species. Experienced birders can identify birds using GISS; all birders can identify birds if they adopt the BBI approach.

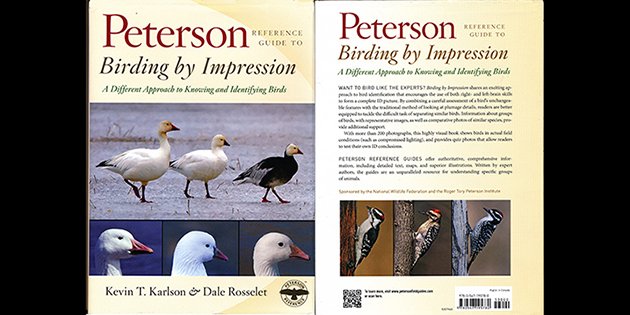

So say Kevin T. Karlson and Dale Rosselet in Birding by Impression: A Different Approach to Knowing and Identifying Birds, the latest addition to the Peterson Reference Guide series and a book likely to revive the continuing discussion about the merits of GISS (the term used in the book, as opposed to the popular jizz) versus traditional bird identification. Adding the more structured BBI (as it is abbreviated in the book) into the mix makes learning and teaching the process of bird identification either more complicated or much easier, depending on your individual learning tendency and how you were originally taught to bird. So many bird identification approaches, so little time!

Karlson and Rosselet introduce BBI in an introductory chapter that articulates rationale, basics, a little more rationale, and applications in the field. The bulk of the book is devoted to heavily illustrated accounts of 35 groups of similar looking birds, offering instructions on how to differentiate species by size, structural features, behavior, plumage pattern and general coloration, habitat use, and vocalization. The result is a different kind of book. It is not a field guide, though it offers a wealth of information about field identification. It is not a handbook, though it approaches species from a collective viewpoint. It is not a textbook, though its aim is clearly instructional. Like other books that have published lately (the Crossley Guides, by one of Karlson’s The Shorebird Guide co-authors, come immediately to mind), it aims to provide an alternative, maybe new, way of thinking about bird identification. The main question for me isn’t whether this is indeed a revolutionary approach, but rather: what does this book offer that is different?

The Karlson-Rosselet BBI approach is theoretically based on hemispheric brain differences, the idea that the left side of our brain processes stimuli analytically in a linear manner and the right side of our brain processes what we see and hear creatively and holistically. Traditional bird identification, a reliance on plumage details expressed verbally, is a left-brain, analytic activity. BBI, they say, introduces right-brain functions into the id brain process, bringing into play “long lasting and readily accessible” impressions of size and shape and movement stored in the subconscious memory; the process is nonverbal, relying on impressions, not words.

It still sounds like intuition to me. Intuition, after all, is rooted in the nonverbal, ‘see the forest not the trees’ part of our brain. I would be more apt to accept the science of BBI if the science of hemispheric brain functions was not subject to so much misconceptions and simplification.* I wish Karlson and Rosselet had cited scientific articles explaining the basics of brain psychobiology to support their ideas. Instead, we get references and quotes from Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, the popular science book that takes bits and pieces from various research projects to make the case that we make choices without consciously thinking. Gladwell is a good read, but not credible scientific support.

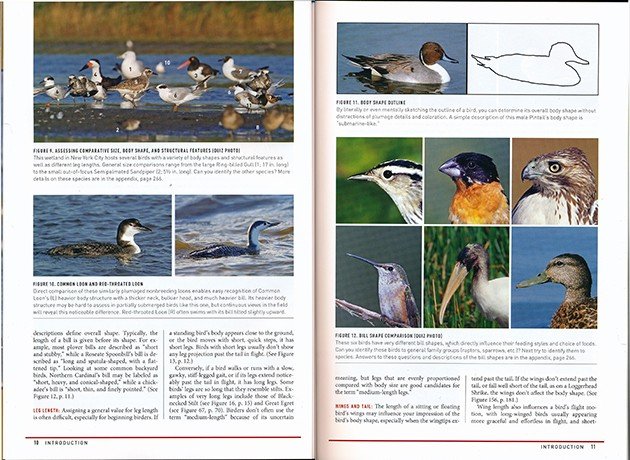

Once I got past the scientific explanations and simply accepted that BBI is an approach worth trying, I found plenty of substantive content in Birding by Impression. “BBI Basics”, which defines the core terms of the approach (size, body shape and structural features, behavior) and supplemental characteristics (plumage patterns, general coloration, habitat use, vocalization) is a necessary prelude to the group species accounts. In addition to talking about the what (as in ‘what is a structural feature?’) and the how (as in ‘how to describe a structural feature?’) attention to paid to the how–how to study familiar birds to use them as the basis for judging the size of unfamiliar birds, how to use photographs to learn the differences in structural features of similar birds. It is a lot easier to describe physical things, which is what field guides do, then to describe a cognitive process, which is what bird identification is.

The bird family accounts are wonderfully informative, especially if you are a birder (like me) who knows enough to know what family a bird belongs to, but still has trouble differentiating amongst specific species within the family. (And, let’s face it, how many birders can say with certainty if a roosting nightjar is a Chuck-wills-widow or a Whip-poor-will, as New York City birders learned a couple of weeks ago?) These chapters differ in length and content, depending on the number of species in each group. Bird families that resemble each other are combined into one chapter, for example “Owls, Nightjars, and Nighthawks,” and are then treated separately within the chapter. This may make taxonomic fanatics faint, but it is useful for learning how to differentiate amongst birds that look alike but really aren’t, like sparrows and longspurs, hummingbirds and swifts.

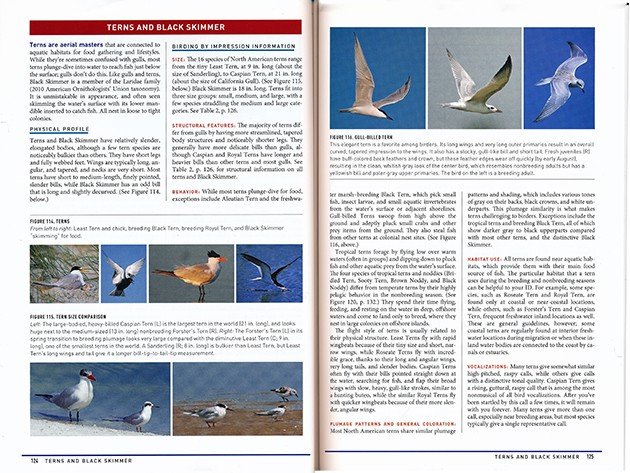

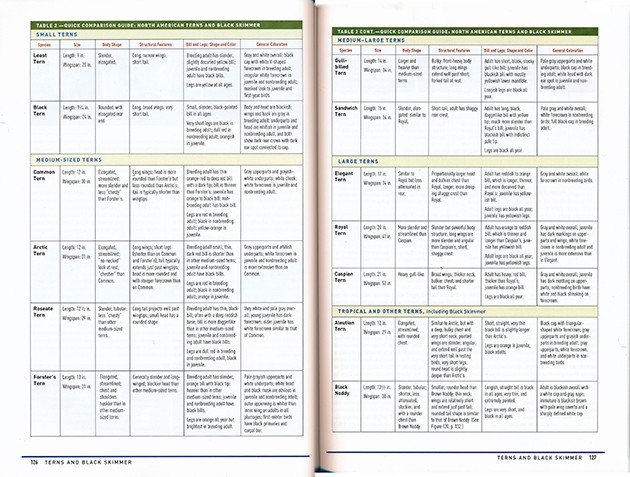

Each Account starts with paragraph encapsulating the physical and behavioral essence of the subject bird group, occasionally adding a brief taxonomic note. A Physical Profile follows, outlining structural and behavioral features the birds within the group share and the exceptions. So, terns “have relatively slender, elongated bodies,” and “most terns have short to medium-length, finely pointed, slender bills” except for Black Skimmers. The Birding By Impression section follows–a longer section that describes Structural Features, Plumage Patterns and General Coloration, Habitat Use, Vocalization. This detailed information gets a little confusing, so we happily have charts, called “Quick Comparison Guides,” for raptors, terns, hummingbirds, flycatchers, and towhees, sparrows, longspurs and buntings. I love the charts, and I only wish Houghton Mifflin Harcourt will publish them as PDFs that can be printed out and carried in the field.

Comparisons of Similar Species, the last section in each Account, is the one most likely to be of interest to the experienced birder. Here the authors spell out how to differentiate Common Tern and Forster’s Tern, Common Redpoll and Hoary Redpoll, Warbling Vireo and Philadelphia Vireo–all the identification conundrums birders argue about and some they may not yet be familiar with. It is a common, for example, to say that Forster’s Tern has whitish wings and Common Tern has darker gray on the wings. But, how often do you hear birders say that Forster’s “has a slightly larger, deeper, blocker head with a squarish rear profile” while Common Terns have a “smaller and more evenly rounded head” or that Forster’s have broader wings, resulting in “a more powerful flight motion with shallower wing beats and a less graceful impression” (p. 129)? Or, that a Hoary Redpoll’s bill “looks like a Common Redpoll’s bill that was forcefully pushed back into its face, with the resulting appearance tinier and more triangular….further accentuated by a steeper forehead” (p. 258). This is the type of comparative identification material that can be heard at hawkwatches and seawatch stations, in books on specific families like hawks in flight, but seldom in field guides, where the emphasis in on describing the individual bird by plumage.

Like The Shorebird Guide, Birding By Impression offers quizzes throughout the book; these encourage readers to interact with the material and put the BBI identification process in action. There are a lot of quizzes–seven in the Raptors chapter, six in the Flycatchers chapter, for example, and if you want to just do the quizzes, they are nicely listed under ‘quiz photos’ in the Index. The Index also lists the ‘comparison guides’ and the BBI topics in the Introduction, which is a nice change from bird book indexes that only include bird names. Back-of-the-Book material also includes quiz answers (titled, for some reason, ‘Appendix’), a Glossary, and a too brief Bibliography.

Like other books in the Peterson Reference Guide series, Birding by Impression is a large, well-bound book with a clean, simple design. Colored boxes and bars are used to set off chapters and sections; subsection titles are underlined; topic titles are bolded; text is doubled-columned; photos of similar birds are set in grid-like formation. The birds in a grid all face the same way (well, almost always, I just found a coot and a gallinule facing each other). The design helps create a book that, despite density of information, book is very readable and accessible, If you are looking for the BBI approach to differentiating Sharp-shinned from Cooper’s Hawk, for example, you can find it pretty easily.

Bird photographs are an essential part of the book, clear, colorful bird photographs used to illustrated descriptions of structural and plumage features and, of course, for the quizzes. The images are all beautiful, but not in a flashy way that distracts or misleads, the exception being some lovely full-page images used to separate main book parts. Most of the photographs are by Karlson, with additional photos by 17 birder/photographers including Lloyd Spitalnik, Brian Small, Mike Danzenbaker, and Bob Fogg.

Authors Kevin Karlson and Dale Rosselet each bring a unique skill set to Birding By Impression. Dale Rosselet is an educator, and tour leader, associated since 1983 with New Jersey Audubon, where she is currently Vice-president for Education. Her spouse, Kevin Karlson, is considered one of the best bird photographers in the U.S.; he is a co-author of The Shorebird Guide (with Michael O’Brien and Richard Crossley, from who he says he first learned to appreciate BBI), an author and co-author, respectively, of two photographic books–Birds of Cape May and Visions: Earth’s Elements in Bird and Nature Photography (with Lloyd Spitalnik), photo editor of The Birds of New Jersey: Status and Distribution (2011), and a keynote speaker, workshop presenter and tour leader at birding festivals. Both are birders first and foremost, both are known in the New Jersey birding community as mentors, and it shows. The book’s writing style is simple, direct, and occasionally personal, with quiet references to the couple’s own experiences and warnings about a particularly tricky quiz.

I am not a stranger to the BBI system. My beginning birder instructor started off my first class by instructing us to describe a bird without invoking its color. I’ve been privileged to bird with some of its major supporters. Still, there are parts of the BBI approach as presented in this book that seem strange. Geography, for example. Range and distribution are essential elements in traditional bird identification. In BBI, it appears to be one of those features that is sometimes invoked and sometimes not. Habitat, which is related to, but not the same as geographical range, is the main BBI element. BBI also appears to be a largely visual process. Though vocalization is listed as a major BBI element, less detail is given in this book to visual clues for differentiating similar species than to listening carefully to bird songs and calls. I have a feeling that the emphasis on the visual is more a product of what the authors could cover in one book, and that the field experience of birding with them would be very different. But, for the beginning birder the emphasis on looking over hearing is deceptive.

I like Birding by Impression. What’s even more important I have used it often in the short time I’ve owned it. Yes, this is a different type of identification guide. And, I don’t think it should take the place of your field guide. (For one thing, it is too big to be carried in the field, for another, this is not the authors’ intent.) And, yes, there are parts of this approach that birders will have difficulty accepting or integrating into the birding process. That is to be expected. This is a book that has a lot to offer birders of all levels. It can be used in different ways–as a beginning skills guide, as a handbook for solving specific identification conundrums (when the field guide just isn’t enough), as a textbook to be studied in preparation for sparrow season or shorebird season, as the source of expertise that will impress all your birding friends (the section on Empidomax flycatchers looks particularly promising). It is a book that I think will add value to your birding reference book shelf.

* There Is No Left Brain/Right Brain Divide by Stephen M. Kosslyn and G. Wayne Miller, Time Magazine, Nov. 29 2013. http://ideas.time.com/2013/11/29/there-is-no-left-brainright-brain-divide/

——–

Birding by Impression: A Different Approach to Knowing and Identifying Birds (Peterson Reference Guides)

by Kevin Karlson and Dale Rosselet

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May 2015.

Hardcover, 7 x 0.8 x 10 inches, 304 pages.

ISBN-10: 0547195788; ISBN-13: 978-0547195780

$30.00 retail, available at substantial discount from the usual suspects.

Leave a Comment