It was July of 2012. I arrived at Lassen Volcanic National Park around 7:00 a.m. It was a cool 48 degrees. I had taken the short drive to the park to search for a family of American Dippers sighted near the visitor center by a fellow birder a few days before. What I found was more than I could possibly hope for.

I parked where I nearly always begin my day at Lassen Park, at the first turn out about 100 yards beyond the northern park entrance ranger station off highway 44. As I got out of my car, about fifty feet from Manzanita Lake, I heard the loud drumming of a woodpecker. Click on photos for full sized images.

I didn’t know what species of woodpecker it was, but I knew it was just in the clearing on the other side of the road. I grabbed my bins, camera and camcorder and headed toward the hollow drumbeat. If not for the drumming, I would probably not have seen the Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus), listed by authors of some field guides as “scarce,” by others as “uncommon to rare.”

Note how well camouflaged this bird is atop a snag in its natural habitat of burned coniferous forest.

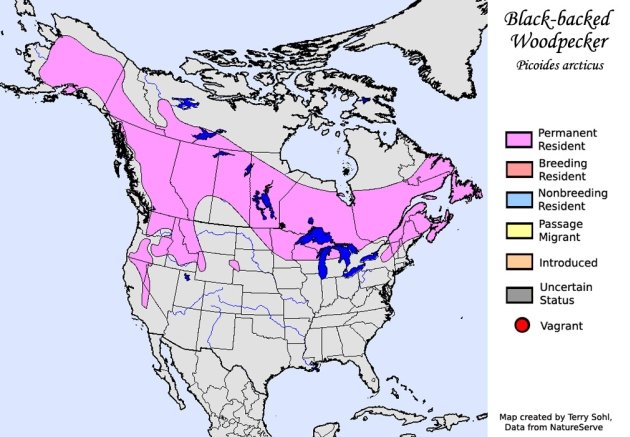

Black-backed Woodpeckers are non-migratory, although there have been documented intermittent irruptions of the species outside their normal range. Some of these irruptions have been attributed to a lack of wood-boring insect prey on their normal range or to overpopulation following an insect outbreak1.

Either way, they are usually due to exploitation of wood-boring beetle larvae, their primary food. Range map courtesy of South Dakota Birds and Birding.

I approached carefully as I listened to the ever growing sound of the drumming, not wanting to flush a bird I had only seen once before.

Black-backed Woodpeckers thrive in forests where fires have burned and are are threatened by logging that destroys their post-fire habitat.

Black-backed Woodpeckers depend upon an unpredictable and ephemeral environment that may remain suitable for at most seven to 10 years after fire; their populations are clearly regulated by the extent of fires and insect outbreaks — and by the management actions people choose to take in those affected forests2.

To protect this woodpecker and the post-fire ecosystems it depends on throughout California, in September 2010 the Center for Biological Diversity and the John Muir Project petitioned to list the bird under the California Endangered Species Act, earning it “candidate” status in the state, which does offer some protections for the bird.

In October of 2012, the Institute for Bird Populations released “A Conservation Strategy for the Black-Backed Woodpecker in California3.” The purpose of this Conservation Strategy is to provide a roadmap for conserving Black-backed Woodpeckers in California through informed management.

A new report was just released January 6th by the Center for Biological Diversity and the John Muir Project outlining the important ecological benefits of last summer’s Rim Fire in Northern California and exposes how a U.S. Forest Service plan to allow 30,000 acres of logging in the burned area will cause significant harm to wildlife, water and the regrowing forest.

The report, Nourished by Wildfire: The Ecological Benefits of the Rim Fire and the Threat of Salvage Logging, explains how fires are essential for maintaining biological diversity in the Sierra Nevada ecosystem4. It is a short, very informative, nine page report that I urge you to read.

I’ll leave you with this video by the US Forest Service that sums up the situation pretty well, plus it starts out with a Black-backed Woodpecker nestling that is really cool.

httpv://youtu.be/Q1UnMDGqG_4

References: 1Birds of North America Online, 2Center for Biological Diversity, 3Bond, M. L., R. B. Siegel and, D. L. Craig, editors. 2012. A Conservation Strategy for the Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) in California. Version 1.0. The Institute for Bird Populations and California Partners in Flight. Point Reyes Station, California. 4Center for Biological Diversity and the John Muir Project (2014). Nourished by Wildfire: The Ecological Benefits of the Rim Fire and the Threat of Salvage Logging. Justin Augustine and Chad Hanson, Ph.D

Thank you for sharing these amazing photos!