The 19-teens were not a good time for North American birdlife. Not more than four years following the final breath of the last living Passenger Pigeon, and at the same facility – the Cincinnati Zoo, whose place in ornithological history is morbidly established – the last Carolina Parakeet died. It was called Incas. And with it the existence of the northernmost species of parrot in the world, the only native parrot in the United States whose provenance is not questioned, and a piece of American natural history that is so bizarre that its existence seems impossible to people living today.

I mean, think about it. The loss of the Passenger Pigeon stings because of the impossible descriptions of the bird’s abundance. Flocks miles long and horizon to horizon. Groves of trees with pigeon dung as deep as spring snow. Bizarre, impressive, amazing stuff.

But though we lost the pigeon, we still have pigeons. Mourning Doves, for instance, while they’re hardly present in those impossible flocks it’s not impossible for us to imagine the familiar streamlined shape of pigeons bolting across the sky. But imagine those flocks are verdant green, a color unmatched by any native bird currently in North American (north of Mexico, of course). Imagine those sun-headed, screeching demons alighting on a stand of cockleburrs or sweetgum or sycamore. Barreling into your feeder with reckless abandon and cleaning you right out. And this from New England to Florida, west as far as the Great Plains. Can you imagine it? Speaking for myself, it’s a lot harder.

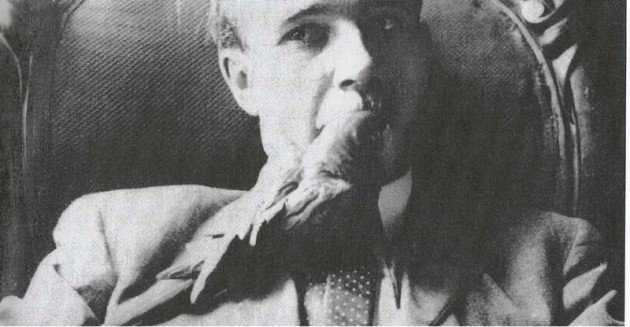

Carolina Parakeet in captivity, one of the few photographs of a living bird in existence. photo from wikipedia

Carolina Parakeet in captivity, one of the few photographs of a living bird in existence. photo from wikipedia

The weird thing about Carolina Parakeets is that, unlike Passenger Pigeons, there’s not a lot of consensus on why the Carolina Parakeet winked out. They were considered in the south to be an agricultural pest, as they laid waste to apple orchards and grape vines. But they were also beneficial as a major controller of invasive cockleburrs. They are also popular in the pet trade and as an adornment for ladies hats, the millinery trade being pretty devastating to many of North America’s flashiest birds. But pets and hats couldn’t have devastated an entire population of millions of birds in such a short time over such a vast area, could they?

Maybe. Because there was one more behavior of the Carolina Parakeet that may have contributed to their decline, at least locally. The birds had a tendency to rally around their fallen flockmates. When hunters would fire into a flock, the survivors would wheel around and return to the dead and dying. Again and again, they’d come back, according to the literature, allowing for hunters to take shots over and over again until the entire flock, and the entire species, is gone.

So yeah, there’s a lot I can’t imagine about the Carolina Parakeet. And some I don’t think I want to.

…

Extinction is forever. A species, wiped off the earth, never to exist again. What a horror! What a disaster! What a wrong!

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

But, in the wider view of things, extinction is necessary. It is what drives evolution. Extinction is what befalls the species that fails to adapt, to survive, to thrive. Most species go extinct. That is just the hard, cold reality of nature, red in tooth and claw.

This is not to say that we should sit back and let the Holocene Extinction continue. No! We must fight to save every species we can, every ecosystem, every niche.

It is the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, once one of the most abundant species in the world. In order to raise our awareness, to remind us of what we have lost, and to inspire us to fight for Every. Single. Species. we are hosting Extinction Week here on 10,000 Birds from 7 September to 13 September. Come back, click through, read, learn. And get angry and take action.

…

Leave a Comment