Do much birding in the city, and your thoughts will turn again and again to feral pigeons. As I have pointed out before, we owe the much-maligned sky rat a debt of gratitude. Introduced as they are over much of their range, they’ve nevertheless become a crucial part of the urban ecosystem, recycling discarded french fries into tasty meals for falcons in a way that surpasses human ingenuity (although there are few stats on the rate of clogged arteries among the falcons in question.)

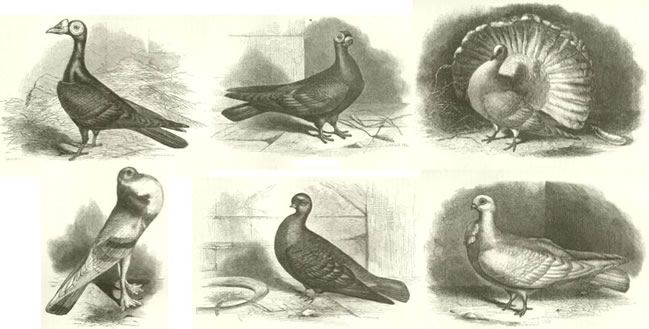

Human ingenuity has found a lot of uses for pigeons, though. Some are fatal on the face of it (squab, skeet-shooting, spying) and others, while they may seem more benign on the surface, have gotten downright weird for the pigeons in question as well. Take the pigeon fancy, or fancy pigeons, however you want to word it. The breeding of pigeons into ever more extravagant shapes helped put Darwin onto the scent of evolution, and has provided a calm and innocent (ok, sometimes not so innocent) hobby for generations of city-dwellers deprived of the comforts of a bucolic lifestyle.

Like everything else that humans choose to domesticate, though, fancy pigeons sometimes get loose into the environment and then matters take on a less cheerful air.

Take a look at this fine feathered fellow (having seen him put the mack on some lady pigeons, I feel fairly confident in assigning this bird a sex) who hangs out behind the grocery store past which I walk my dog, living on discards and handouts with a large flock of his kin. Unnatural selection indeed:

None of these are traits that particularly recommend themselves in a wild bird. To start at the bottom, the fringe of feathers around the feet seem like they would pick up filth, and they can’t be good for thermoregulation in our current weather. The light color is like a beacon to predators in most environments. The weird little crest is decidedly un-aerodynamic. And then there’s the beak. I haven’t measured this particular specimen myself, but some breeders of short-beaked pigeons are known to take things to extremes that prevent the birds from feeding their own young. In pigeons, the male and the female both participate in feeding the young. Even if this bird does succeed in his courtship, will he just be producing babies doomed to starve, or to survive, only to pass on genes that could crop up damagingly in future generations?

And yet here he is, not getting eaten or run over or even looking particularly bedraggled. Courting, mating. He doesn’t look like any particular breed that I’ve come across (although the breeds of odd-looking pigeons are legion and I could have missed one) which suggests that his ancestors, at least some of them, managed without human assistance for a few generations now. Just like their more illustrious ancestors, pigeons sometimes prove that life finds a way.

Leave a Comment