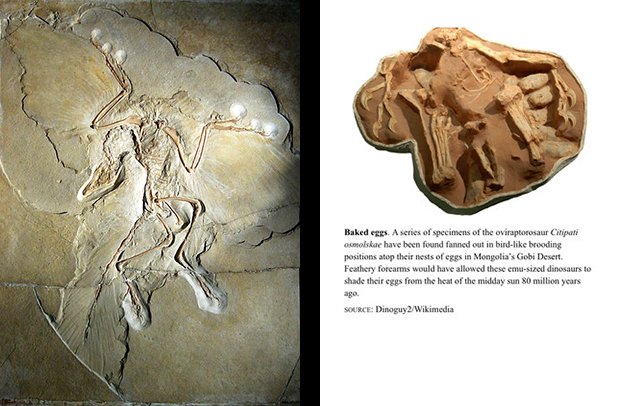

My knowledge of dinosaurs started and stopped with Jurassic Park (the movie, not the theme park), Patrick’s Dinosaurs, a charming book my daughter read in grade school, and, most recently, visits to the American Museum of Natural History with my nephews. In my runs through the dinosaur halls with Jake and Zach, I’m pretty sure I saw Deinonychus, the small fossil that inspired the velociraptors in Jurassic Park and, more importantly (in some minds), revived a 19th century theory that birds are descended directly from dinosaurs. I probably missed the fossilized remains of a nesting oviraptorid found in Mongolia in 1994, located in the hallway leading to the Hall of Saurischian Dinosaurs. These fossils are seen as proof that some dinosaurs brooded over its eggs. Like birds. But, somewhere along the way, probably by reading posts by Greg Laden, I did learn that great strides have been made in proving the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. So, I welcomed the opportunity to read and review Flying Dinosaurs: How Fearsome Reptiles Became Birds, by John Pickrell, published in the United States by Columbia University Press.

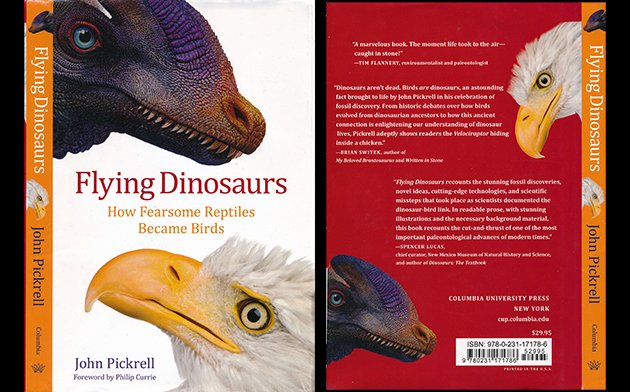

Don’t let the university press imprint deceive you. In this highly readable book, Pickrell aims to explain and summarize the diverse strands of current activity, research, and controversy involved in proving this once scorned theory, from paleontological digs in China and Mongolia, to anatomical analyses of flight, to fossil fraud in China, to micro-analysis of feather pigmentation, to a recreation of how dinosaurs made sounds, to the possibilities of DNA reconstruction. And, he places current research within a framework of paleontological history of intrigue, backstabbing, and name-calling feuds. (No, not a reality show, the history of paleontology in the United States is apparently livelier than the Indiana Jones movies.) Pickrell, an Australian science writer who grew up in Great Britain and studied for his master’s degree at London’s Natural History Museum, is clearly engaged with his subject. His enthusiasm and imaginative scenes of what feathered dinosaurs looked like and how they behaved is likely to draw in even the most non-scientific oriented person; his stubborn insistence on talking about every single aspect of feathered dinosaur theories and paradoxes and argument, citing numerous scientific papers and quoting current paleontological and evolutionary experts, is likely to gain the respect of readers of a more hardcore scientific persuasion.

Two fossil images reproduced in Flying Dinosaurs: The Berlin specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica (left, H Raab/Wikimedia) and Specimens of the oviraptorosaur Citipati osmolskae found in the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. “Feathery forearms would have allowed these emu-sized dinosaurs to shade their eggs from the head of the midday sun 80 million years ago” (right, Dinoguy2/Wikimedia).

The book begins with the discovery of Archaeopteryx in Germany in 1861. Seen now as the transitional creature between birds and dinosaurs, the significance of this small fossil, which had wings and a bony tail, was not acknowledged until the discovery of Deinonychus (my AMNH fossil) in 1964 by John Ostrom. Ostrom resurrected the 1868 theory of T. H. Huxley, an evolutionary biologist, that birds evolved from dinosaurs, but it was still a rocky ride. No collarbones! No feathers! No flight! And then, in 1996, a farmer/fossil-hunter named Li Yinfang found a unique fossil in his home province of Liaoning–a beautifully preserved turkey-sized creature that clearly had feathers. The new species was subsequently named Sinosauropteryz prima, ‘first Chinese lizard wing’. Its discovery disrupted the paleontologic community, and it hasn’t been the same since. Not only did dinosaurs have feathers, evidence was found of collarbones. And, flight became a secondary consideration as fossils of new species, found in rapid succession in Liaoning, indicated that feathers were used for courtship displays. Things got more complicated when evidence was found that even the larger dinosaur species, such as tyrannosaurs, probably had feathers.

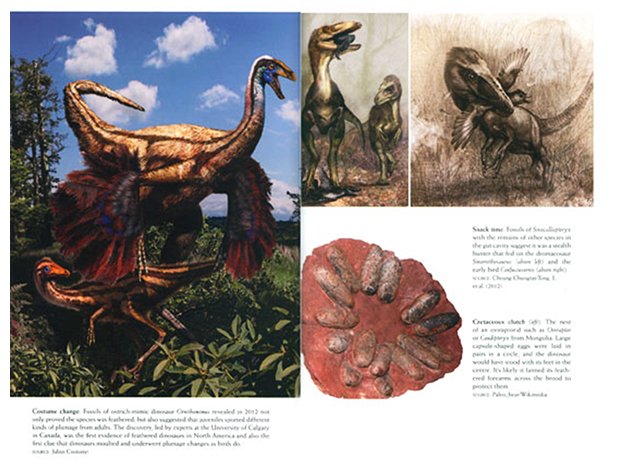

There is a lot of science here to explain. Pickrell puts the pieces together in 11 chapters. He writes about the “find of the century’ and the resistance of some scientists to accepting evidence that birds are descended from theropods, small, bipedal carnivorous dinosaurs in the first two chapters. Other chapters cover research on evolutionary connections made through behavior, anatomy, rate of growth, and disease; feathers and the logical and crazy theories that have been presented on how dinosaurs were able to fly; scientific techniques that allow scientists to figure out the surprisingly bright colors of dinosaur feathers (orange striped tails!); the shocking revelation that some dinosaurs, probably males, protected their eggs with feathers spread out over the nest; and recent proposals to resurrect dinosaurs using bird DNA. People and history come into play in “The dinosaur hunters,” a chapter on larger than life personalities such as E.D. Cope and O.C. Marsh, who feuded in the 19th century, and today’s superstar, the young, prolific Chinese Xu Xing, “China’s answer to Indiana Jones.” A chapter on the infamous National Geographic incident, in which a Chinese faked fossil fooled some of the most notable dinosaur experts, is disturbing, as much for the willingness of experts to believe what they’re told as for the greed of the fraud perpetrators. The last chapter, “The survival game,” explores the question: why did dinosaur-like birds (and crocodiles and turtles), survive the great cataclysm that caused the extinction of our beloved big, bad dinosaurs? It’s a question for which we’ll probably never have definite answers. But, then again, who thought we would ever know the color of dinosaur feathers?

For the most part, Pickrell’s prose is that of the experienced science writer, clear, concise, organized, occasionally inserting himself, but never too subjectively. The book has its origins in Once Were Dinosaurs, a 2010 article by Pickrell published in Cosmos, an Australian science magazine. There are some sections, especially in the first two chapters, where you can see Pickrell struggling to rewrite–a little too much repetition, a little too much reliance on quotes from the paleontologists he interviewed. We read many quotes from Phil Currie of the University of Alberta, one of the world’s foremost, paleontologists, who wrote the book’s forward. Later chapters read more smoothly. I especially enjoyed “Colouring in the dinosaurs,” the chapter on the value and discovery of color in birds and dinosaurs. I drank in the images section, which features artists’ images of what feathered dinosaurs might have looked liked. The drawings and painting by artists such as Luis Rey and Lida Xing look more like science fiction/fantasy images than scientific illustration, though they are carefully researched and thought out.

Images of ostrich-mimic Ornithomimus by Julius Csotonyi, their fossils indicated that juvenile plumage differed from adult dinosaur plumage; drawings of Sinocalliopteryx and early bird Confuciusornis by Cheung Chungtat; nest of an oviraptorid, large capsule-shaped eggs laid in pairs in a circle, from Wikimedia.

Since this is not an academic book, the scientific articles are listed as references in the back of the book, chapter by chapter. Pickrell makes clear how the articles are used in the body of the book, and includes the web sites of all contemporary articles. (Unfortunately, not all of these articles are accessible to readers who don’t have access to gated scientific journals like Nature.) The journal and book citations are written out fully, just as they would be for an academic book. Surprisingly, similar documentary attention is not paid to the many interviews Pickrell uses throughout the book. We are simply told “Quotes and information not specifically referenced here are drawn mainly from a series of interviews conducted between July 2012 and August 2013, and also from earlier research…” I really would have liked a more formal list than thank you’s in the Acknowledgments.

Back-of-the-book material also includes a chart of “Relationships of the theropod dinosaurs” and “An A-Z of feathered dinosaurs”. I found both features extremely helpful, especially when reading the first few chapters. Archaeopteryx stays in my head, but I tend to get Dilong paradoxus mixed up with Gigantoraptor erlianensis. There is also a brief, 2-page Glossary, a brief “Select bibliography” of books, and an excellent Index. I think Pickrell underestimates the intelligence of his readers by not including at least two or three seminal scientific articles and sources of current scientific news in the bibliography. Journal articles might not be easy reading, but by only listing books he undercuts the message of the rest of the book, that it is essential to keep up with the scientific literature if you are going to track new developments. And, there are many online sources for paleontologic advances available.

Flying Dinosaurs: How Fearsome Reptiles Became Birds is an example of good, solid scientific writing. It presents complex research and theories in understandable language; it elaborates on the background of the papers with interviews from key players and historical anecdotes; it further sparks the imagination with detailed descriptions and art images of what may have been. It is the perfect book for birders who, like me, would like to learn why we now think that birds come from dinosaurs. And, for birders who have been keeping up with the literature, it most probably presents related research and theories you didn’t know about. This is an every advancing field; witness the latest article from Xing Xu, et al, “An integrative approach to understanding bird origins”, from the December 12, 2014 issue of Science, which Greg will be explaining to us over the next few weeks in 10,000 Birds. It is hard to understand current models if you don’t know the history of the research behind them.

If you are of a certain age, like me, there is a certain shock and sadness in losing the images we grew up with–the predatory Tyrannosaurus Rex, the massive but shrub-eating Triceratops, and the other big, bad boys of B-movies like The Lost World. These dinosaurs were a dull gray or brown with leathery, stiff skin and they were mean and cold-blooded. You would never catch them using feathers on their tails to attract a mate or brooding over a clutch of eggs. But, if we’ve lost iconic images, we’ve gained images of colorful possibilities and a sense of wonder over this new knowledge and its implications. Which includes, I think, a new respect for birds and their biology. Just think! Birds came from dinosaurs. And, some of that dinosaur gene pool still exists in birds. It’s all truly amazing.

———————-

Flying Dinosaurs: How Fearsome Reptiles Became Birds.

By John Pickrell, Foreword by Philip Currie.

Columbia, University Press, September 2014.

240 pages, 26 illustrations.

ISBN-10: 0231171781; ISBN-13: 978-0231171786

Hardcover, $29.95

Available in e-book formats, including Kindle ($9.99) and eBook ($12.99)

Leave a Comment