My connection with Ghana began rather unexpectedly (and as it turned out, rather humorously) more than ten years ago. I was in contact with a group of birders for whom I arranged and guided an annual tour to Africa. During each trip we would discuss a destination for the following year. We already had South Africa, Zambia and Uganda under our belts, but my clients’ request for the next year came right out of the blue: Ghana! I must admit that I was astonished as I had never considered Ghana a potential birding destination, nor knew of any birders who had ever been there. My clients insisted that they wanted to go to Ghana as they had heard that the birding was great. Since the customer is king, and not needing a better excuse for exploration, adventure and an opportunity for new birds, my colleague David Hoddinott and I, soon found ourselves winging our way to this West African nation. Very little information was available at the time, so we hired a car and off we went, following the few tips we had managed to gather but mostly our noses. And wow, what a trip we had! Nineteen days later we had racked up an amazing list of 436 species, including some of Africa’s least known birds such as Congo Serpent Eagle, Yellow-footed Honeyguide, Tessmann’s Flycatcher, Yellow-bearded Greenbul, Black-collared Lovebird and much besides. We also knew we had discovered Africa’s next hot birding destination.

Blue-moustached Bee-eater is rainforest species occurring in just a few scattered sites in Ghana, it was previously considered a subspecies of Blue-headed Bee-eater.

Back home I meticulously planned the perfect birding route based on our explorations, made the bookings and confirmed the first commercial birding tour to Ghana. About a month before departure my clients asked me if we were going to the same sites in Ghana as the offerings of another, rather upmarket, birding tour company. After some initial confusion on my part, and knowing with certainty that said company did not offer tours to Ghana, it suddenly struck me… my clients had wanted to go to The Gambia all along, but had got the country name confused with Ghana! The Gambia, a cheap package holiday destination for British sunseekers had become quite popular with birders. It is situated outside the rainforest belt, offering mostly dry savanna bird species, waterbirds along the Gambia River and Palearctic migrants. But it was too late for these somewhat geographically challenged birders – tickets to Accra had been booked and plans were in motion… We ended up enjoying a highly successful birding tour, and since then Rockjumper Birding Tours has arranged and guided more than 20 Ghanaian birding tours, recording well over 600 species, including several new bird records for the country.

Africa’s only rainforest canopy walkway in Kakum National Park. Although this park was logged in the past, as a national park it is one of the few forests in Ghana that is really protected.

What makes Ghana so special? Most importantly the Upper Guinea forests, one of Africa’s two major rainforest regions (the other being the far more extensive Lower Guinea forests of the Congo basin and surrounding areas). The Upper Guinea forests are one of the world’s 25 most biologically diverse and endangered ecosystems and are also classified as an Endemic Bird Area, with nearly 20 endemic birds, most of them threatened by extinction. Recently I revisited Ghana after more than 8 years, spending most of my 12 day trip in this forested region of Ghana. I returned home with very mixed feelings, which have spurred this article.

Children of Bonkro Village, Ghanaian’s are widely recognized as extremely friendly and welcoming people.

Ghana’s people are just as friendly as before. Experienced world travelers often leave Ghana stating that its citizens are the friendliest people in the world and I wholeheartedly agree. However, there are a whole lot more Ghanaians now! The population has grown by more than 27% over the last 10 years and is now at over 24.2 million people (2010 census). In 1960, soon after independence (Ghana was the first subSaharan African country to obtain this in 1957) Ghana had 6.7 million people, meaning an incredible 261% increase in 50 years! This obviously has to have an impact on the environment and tragically, this impact is devastating. The birding however was superb, even better than I remembered it. Our tours prove this as we get more and more species each tour (our most recent tour scoring up to 529 species). Furthermore, several birds that were considered extinct or not occurring in Ghana have been found to exist, such as White-necked Picathartes and Nimba Flycatcher, both threatened Upper Guinea endemics.

White-necked Picathartes or Yellow-headed Rockfowl, one of Ghana’s star birds.

The picathartes’ makes for a great story. These strange birds are two species in their own family; White-necked or Yellow-headed, endemic to the Upper Guinea forests and Grey-necked or Red-headed, restricted to Lower Guinea forests. They are large passerines and research has shown them to be an ancient basal offshoot from the passerine tree (at approximately the same time as rockjumpers, were even placed in the same family until quite recently). Their strange appearance and habit of communally nesting in rock overhangs has given them their alternative name of rockfowl, and before that Bald-headed Crow. Colonies of White-necked Picathartes were historically recorded throughout the rainforest zone of Ghana but relentless forest clearance had resulted in all known populations being destroyed, and it was considered extinct in Ghana when I first visited. We actually spent considerable time searching unsuccessfully for this highly sought-after bird; however I did suspect they were not gone, as several hunters I interviewed knew the bird and claimed it still existed. Then a few years ago the news broke that picathartes had been rediscovered at a community forest reserve in Ghana. Researchers then explored surrounding areas and several more colonies were discovered (some of this research, including aerial surveys was supported by funds from the Rockjumper Bird Conservation Fund). One of these colonies has now been opened to tourism after researchers studying the birds deemed visits by birders to be non-disruptive.

We visited the colony at a remote village in the central region of Ghana called Bonkro. Here local hunters had known about the colony and for generations had been harvesting the birds by simply picking the adults off their nests during the breeding season. Now that the colony is off limits for hunting, the population has grown and the village is benefitting tremendously from entry and guide fees, and a school is being built courtesy of conservation funds. We arrived at Bonkro village in the afternoon and once we had met our local village guide and managed to escape the friendly throngs of children, we walked through village fields of cocoa, corn and other crops. Vast tree stumps indicated these fields had recently been primary rainforest. Finally we slipped into the dark forest and followed a meandering trail for 3km, passing massive forest giants with expansive buttress roots, until we reached a very steep rise. After a sweaty climb of a hundred metres or so, we reached the colony of mud cup-shaped nests stuck against the walls of a rock overhand. We quietly arranged ourselves on a nearby rock and waited. The picathartes spend their days foraging for insects, snails and other prey deep in the forests and very little is known of this behavior as they are incredibly shy birds, disappearing at the first signs of disturbance. However, around their colonies (to which they usually return each evening) they seem to lose their fear, perching close to observers to preen, sometimes ignoring observers and at other times displaying great curiosity. I had seen the Red-headed Picathartes in Cameroon on several occasions, and was on my way to a White-necked colony in Ivory Coast in 2002 when a coup broke out and we had to reluctantly turn back, so finally seeing this bird was a dream come true for me, and what a show they gave us!

Seeing White-necked Picathartes was a dream come true for the author!

However all is not rosy. In my three visits of several hours apiece, waiting for and then watching these amazing birds, our entire stay was accompanied by the constant roar of chainsaws and blasts from bushmeat hunters’ shotguns, the two great evils that are destroying much of Africa’s rainforests and their fauna. Figures I could obtain indicate that Ghana’s forests have reduced alarmingly from 8.2 million hectares at the beginning of the 20th century to a mere 1.4 million hectares in 2007. According to the World Bank, up to 80 percent of Ghana’s forests had been destroyed by illegal logging by 2008. Official estimates suggest that logging is proceeding at about four million cubic meters per annum – four times the sustainable rate. Ghana has the dubious distinction of being the first country to have lost a major primate species since the Convention on Biological Diversity came into force: Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus was declared extinct in 2000 due to forest destruction. Between 1990 and 2010, Ghana lost 33.7% of its forest cover (around 2,5 million hectares, nearly double what now remains!) Most tragic is that what remains is still being destroyed at a devastating rate. At every forest we birded (except Kakum National Park which was logged until 1989), logging was actively taking place. All these forests are in “protected” forest reserves, however at some, logging permits are reportedly being issued for harvesting of these forests. Whether permits being issued are for selective harvesting or not, what is undeniable is that these reserves are being clear-felled.

Despite birding in shattered forests with the constant background whine of chainsaws, the birding is phenomenal, with an incredible diversity and volume of rare and endangered species. This image (by Marius Coetzee) shows Adam Riley & David Hoddinott with a group in Nsuta Forest, a forest reserve that is in the process of being clear-felled and settled by subsistence farmers. The rare Rufous Fishing Owl was one of the many species seen by the group here.

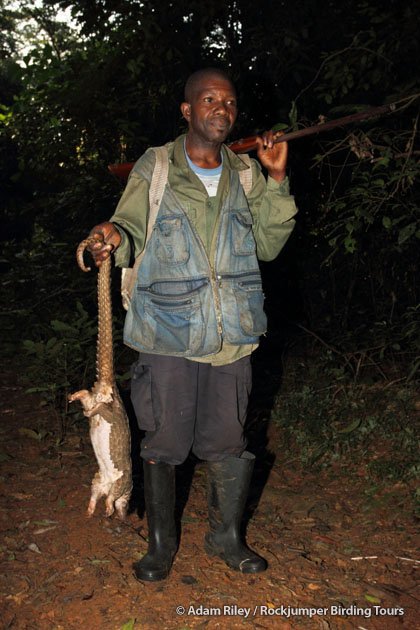

At the same time, the last remaining larger mammals and birds are being blasted by hunters to supply the insatiable demand for bushmeat, a market that in Ghana alone is estimated to generate revenues of up to US$350 million per annum. Although this hunting is in many cases illegal it is brazenly undertaken by hunters, and their victims (including endangered species) are commonly sold along the main roads of the country. I have seen both Long-tailed and Tree Pangolins, Greater Cane Rat, several species of monkey and duiker, Royal Antelope, Pel’s Anomalure (a giant flying squirrel), huge casqued hornbills, Great Blue Turacos and numerous other birds and mammals for sale along the roadsides. Whilst in Atewa Range Forest Reserve, a hunter passed us deep in the forest and I asked him to show us his night’s catch. He opened his rucksack and inside was a tightly bound bundle that he unfastened to reveal a Tree Pangolin – a creature I had never seen alive in all my time birding these forests. It was completely unharmed as the hunter had climbed a tree to catch it, so we agreed to purchase the poor animal and after taking a few images and ensuring the hunter was gone, we released it and with mixed emotions watched as it climbed high into a massive tree. What are the chances of survival for these shy forest denizens?

An illegal hunter in Atewa Range Forest Reserve with his catch, a Tree Pangolin destined for the bushmeat market.

This lucky Tree Pangolin was unharmed and here on its way to freedom after we purchased it from the hunter.

Although the larger, edible birds are all but gone from most of Ghana’s forests, as mentioned, the birding was superb. Flock after flock was encountered in all levels of the forests, often a mind-boggling diversity of species were present even in seriously degraded forests that were in the process of being clear-felled. This included such endangered species seen by our groups in December as Rufous Fishing Owl, Western Wattled Cuckooshrike, Red-fronted Antpecker, Green-tailed Bristlebill and Rufous-winged Illadopsis. This led me to the conclusion that these birds are the displaced survivors from vast areas of cleared forest and are thronged in unnaturally high densities in these last remaining forest pockets. However they will not and cannot breed, and once these individual’s natural lifespans are over, these bird populations will be lost forever. This certainly raises a question of ethics for any birder contemplating a visit; should you hurry to Ghana’s forests and witness the last of this diversity as it is being destroyed or is it better to simply stay away?

The little known and seldom encountered Red-fronted Antpecker, these are the first known photographs of this rare species.

Is there a solution? If there is, it will certainly be very complex. With an economic growth rate of over 20%, Ghana is listed as “The World’s Fastest Growing Economy in 2011”. This combined with a burgeoning population that is becoming more and more affluent, is creating an unsustainable demand on the land. The supply of legal timber cannot come close towards meeting the demand generated by the growing economy. Some stats include the fact that over three million rural Ghanaians depend on forests for survival, and about 69% of all urban households use charcoal for cooking and heating. A 2006 report titled “Forest Governance in Ghana – a NGO perspective” drafted by Forest Watch Ghana stated “Ghana’s forestry sector is in deep crisis. The timber industry-led assault on this resource is building towards ecological catastrophe. The state’s failure to capture even a minimal portion of resource rent for the public and for the communities that own and depend on these forests for their livelihood has created a social catastrophe. The descent of affected communities into poverty, social decay, conflict, and violence threatens a political and security catastrophe as well.”

A tragic perspective, Adam birding from a logging truck at a stake-out for one of the world’s rarest birds, the Western Wattled Cuckooshrike.

I spoke at length with some members of the community at Bonkro. Their community forest is in a forest reserve and they are not benefitting from the logging, it is often outsiders who obtain permits by reportedly dubious means that are robbing not only these communities of a large part of their livelihoods, but also the world of its biological inheritance. That being said, a section of the forest around the picathartes colony has been set aside as a non-hunting and non-logging area and I guess time will tell whether this “island” will be large enough to sustain these special birds? Bribery and corruption at official levels are obviously massive issues and without the will and support of the authorities, it seems that any conservation effort will be dead in the water. However various NGOs and other conservation bodies have had successes in Ghana and have created protected reserves such as the Wechiau Community Hippo Sanctuary. My thinking (and my professional background is not conservation, so these are just my personal and amateur musings) is that if community members are given an alternative option to forest destruction and hunting, they will embrace these. I had a very long conversation with the pangolin hunter at Atewa and he realizes that he and his fellow hunters are plundering the forest’s resources at an unsustainable rate, but he has a family and has to bring food to his table and no other alternative opportunities exist for him. However, one of the few ways to bring opportunities and income to these communities is through ecotourism; from employment as guides, lodge and support staff and through to entry fees, land rentals for lodges etc. Furthermore, when communities observe people that have travelled across the world to enjoy their wildlife and forests, they realize that what they have is special and should be protected. By empowering the communities both financially and educationally, they will gain the power to resist higher authority’s attempts at destroying their resources and they themselves will also have the will and means to protect their natural heritage. Ecotourism is unlikely however to support very remote communities and it also has its limitations and risks so in no way am I proposing that it is the sole solution. Internationally funded conservation NGOs, carbon credit schemes, poverty alleviation and education (especially of women) programs, family planning schemes, introduction of modern intensive agricultural methods, creation of real protected reserves, sustainable economic development that doesn’t primarily rely on natural resource extraction and tackling of corruption at a local official level are all vital factors that need to be interwoven into a nationally supported conservation strategy if there is to be any hope of saving Ghana’s remaining rainforests.

Another of Ghana’s forest gems, the seldom encountered Fraser’s Eagle Owl.

Blue Cuckooshrike, a highly sought-after rainforest canopy species.

Man, another excellent article. I hope it encourages enough people to make conservation progress in Ghana.

I have found the Ghanaians to be the friendliest of people.

This was a really interesting post, Adam. I’m living off and on here in Ghana while developing a business and I could relate to much of what you say regarding challenges to wildlife. It’s good to hear that so many birds survive here, and I agree that when communities realize that ecotourism can be a means of economic development, people will protect the animals. Please contact me if your tour company plans future tours in Ghana!