“Get a field guide!” That’s what novice birders are told, over and over. But, sometimes an appreciation of birds and birding requires more than a reference book with images of birds and facts about their identifying field marks. There are large avian handbooks and small ‘how-to bird’ guides, and quite a few excellent books of both types have been published. And there are books like Ted Floyd’s recently published How to Know the Birds: The Art and Adventure of Birding, which approach birding with a mix of facts and personal experience, offering essays which convey the joy and wonder of the birding experience as well as information about bird behavior, migration, conservation, and best birding practices. Written in a friendly, inclusive style quietly grounded in science, How to Know the Birds is an excellent addition to the growing list of birding essay books by talented birder/writers like Pete Dunne and Kenn Kaufman.

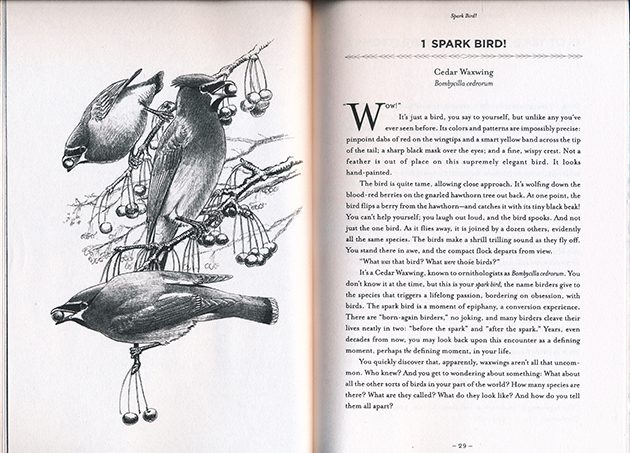

How to Know the Birds talks about 200 commonly found birds in North America (including one extinct bird, the Passenger Pigeon) in 200 brief essays, each exactly one page long. But, it’s more than that, because each essay also includes “a big idea, a method or technique or resource, about bird study in our age” (p. 21). And, each essay tells a story. This is the essence of the book, it is, as the author says, “a storybook for bird lovers.”

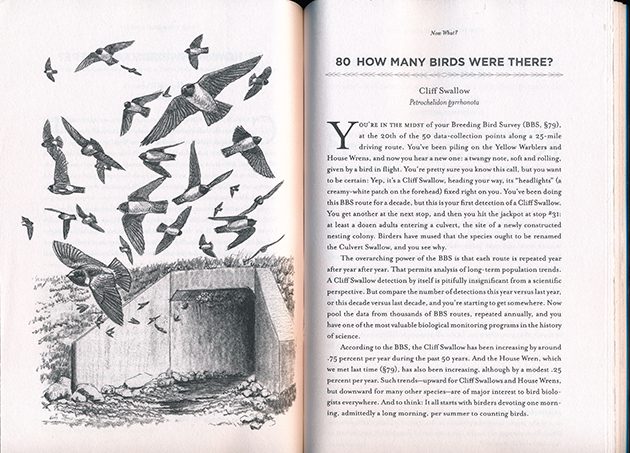

The essays are arranged in thematic order grouped in six sections: “Spark Bird!” (basic points, like bird names, plumage differences); “After the Spark” (birdsong and migration); “Now What?” (breeding birds, breeding bird surveying, eBird documentation, other activities); “Inflection Point” (molt, climate change’s effect on birds); “What We Know” (birding tools and scientific techniques); “What We Don’t Know” (taxonomic puzzles, open questions about bird behavior, ethics and morality). The sections are also labeled according to the months of the year, the idea being that the book will take us through a year of birding. This doesn’t always hold true, many of the observations described could take place anytime, but it does emphasize seasonality, an important aspect of birding, and one it may take time for a beginning birder to grasp (I know I took a long time getting it!). Many essays, especially in the later sections, end with a question, hopefully getting us to think more about questions of ethics, conservation, and the puzzles posed by nature.

So, for example, Essay #15, “Individual Variation,” uses Herring Gulls to introduce the concept that one species, even one species at a specific age, can vary widely in appearance. Essay #61, “The Logic of Migration: Wing Morphology,” discusses the long, pointed, dark wings of the Swainson’s Thrush, and how they are made for long-distance migration (aerodynamic advantage and strength from the melanins that make up the black pigment). Essay #96, “Bird Nests: Classics,” wonders at the exquisite nest building skills of the Pine Siskin, comparing it to “self-directed machine learning.”

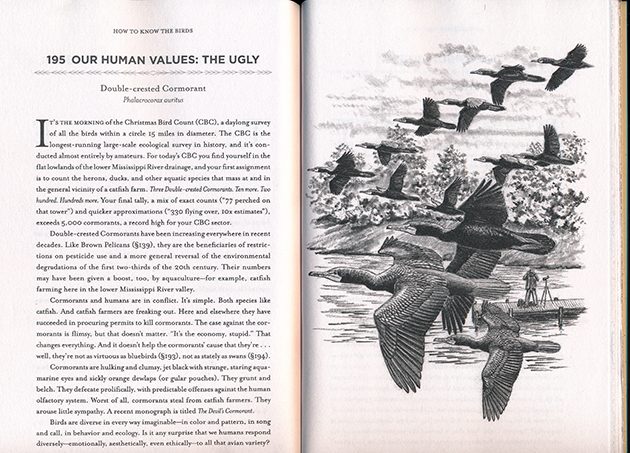

Essay #120, “The ‘Basics’ of Molt,” describes the molt cycle of the Eastern Wood-Pewee, introducing concepts of prebasic molt and plumage cycle. Essay #158, “Things Birders Do: Big Years,” starts with the writer’s observation of a Barn Owl and then defines a Big Year, surprisingly celebrating it as opportunities for solitary introspection. And, Essay #195, “Our Human Values: The Ugly,” describes the standoff between catfish loving Double-crested Cormorants and catfish farmers in the Missouri Valley. I’m not sure if “the Ugly” refers to the cormorant itself or human reaction (catfish farmers are officially allowed to shoot the birds).

Each essay is entitled with the “big idea,” subtitled with the name of the bird species (common name and scientific name), and numbered. The numbers are important, because as we get into the later pages of the book, Floyd refers to past ideas by essay number, reminding us of what we’ve already learned. The “big ideas” build on each other; by the end of the book, we’re not only familiar with the many facets of bird identification, molt, migration, range and distribution, we’ve also been exposed to technical terms like ‘hyperphagia’ and ‘nidification.’ It’s a gentle (maybe even sneaky–in a good way?) way of teaching laypeople the vocabulary of the experts.

As much as I love reading about birds, my favorite section is “What We Know,” in which Floyd writes, one by one, about all the things birders do–travel, eBird, read book, attend ornithological society meetings and birding festivals, join bird clubs, list, chase, patchwork, participate in LISTSERVS, and so on. There is also a bit of science thrown in–bird banding, remote sensing, museum collecting–not everything, but enough to give the beginner a taste of the ornithological side of the birding passion. So many birding books talk only about birds, it’s fun to read about us for a change. As I read these chapters, I imagined a new birder reading them, and getting excited about all the activities this seemingly simple hobby offers. (I do need to note that a rare error crops up here–LISTSERV is not a generic electronic bulletin board, it is a propriety product owned by a company and the use of the term is protected by trademark law. It’s spelled this way, all caps, because that is the official name.)

How to Know the Birds is illustrated with full-page drawings by N. John Schmitt, who illustrated Raptors of Mexico and Central America amongst many other books and magazine articles. I counted 45 illustrations, including five in the Introduction. The black-and-white drawings here are very different from the technical illustrations Schmitt created for identification guides like Raptors. They deftly capture birds in their habitat and in action, nicely complementing Floyd’s stories, yet never losing an underlying anatomical specificity.

The back of the book offers an excellent index, covering birds, people, and vocabulary. I was puzzled as to why the index didn’t include a way to locate the chapters about specific birds, and then realized that this is part of “An Annotated Checklist of the Bird Species in This Book,” another back-of-the-book section. The Checklist is more than a taxonomic listing of species and chapter number and title; it also contains useful notes on each bird family. Finches, for example, are “especially prone to nomadism,” and Falcons, as many experienced birders know, are more closely related to parrots and songbirds than to hawks and eagles.

A note about the selection of birds: there clearly was an effort made to include common birds from all over North America–those found north to south, east to west (Northern Mockingbird), eastern birds (Eastern Bluebird), and western birds (American Dipper). I do wish that there could have been some way to also include notes on geographic distribution, in both the Checklist and the essays themselves. I understand that this is a complicated undertaking, but a new birder reading this book would have no idea that Bushtits (#92: “Breeding System: ‘It’s Complicated'”) are only found in Western states. Or, that the grassland Burrowing Owls of Essay #90 (“Breeding Systems: Coloniality”), who require prairie dogs for successful nesting, are different from the Burrowing Owls of Florida, who are able to create burrow nests and breed without the ‘dogs.’

Ted Floyd is probably best known as the editor of Birding magazine, the informative, handsome periodical of the American Birding Association, and as the author of many ABA Blog posts. (In fact, he has started a series called “How to Know the Birds,” continuing the work in his book, only even better in a way because the blog posts include links to articles and playable bird song.) Floyd has also written the ABA Field Guide to the Birds of Colorado (2014), the Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America (2008), and co-authored the Atlas Of The Breeding Birds Of Nevada (2007), plus numerous articles–over 125–in popular magazines and scholarly journals. He received a B.A. in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology from Princeton University and a Ph.D. in Ecology from Penn State University. (I don’t usually cite the academic credentials of authors, but I thought this was interesting since the official bio for this book is all about Floyd’s popular education activities.) Ted is also a birding friend of mine (it’s a small birding community), though we’ve never met face-to-face. As you can see, that hasn’t stopped me from my usual nitpicking.

Ted Floyd took the title How to Know the Birds from a 1949 book by Roger Tory Peterson, but the content is uniquely and wonderfully his own. These essays are captivating, shining with the author’s warmth, teacherly patience, quiet expertise, and literary skill. Floyd’s writing style draws the reader in, including us in his experiences and observations, making the personal communal. There is also quite a bit of discipline in these essays; it’s a lot harder to write a very short, personal yet informative piece than to ramble on and on. Floyd makes it all seem effortless. Beginning birders will both enjoy and learn a lot from reading How to Know the Birds: The Art and Adventure of Birding. Intermediate and advanced birders will benefit as well, but in a different way. Ted Floyd has been birding for decades, and still finds ways to rejuvenate his joy. He embraces the Internet and social media, he adores eBird, he wonders at taxonomic unknowns, and he sees ecological problems as opportunities for positive change. I love his optimism and passion and his ability to put all that into stories, and I think you will too.

How to Know the Birds: The Art and Adventure of Birding

by Ted Floyd

National Geographic, March 2019, 304 pages, 6.3 x 1 x 9.3 inches

ISBN-10: 1426220030; ISBN-13: 978-1426220036

$28 hardcover; (discounts from the usual suspects); also available in ebook formats.

Leave a Comment