One reason so many of us love birding is that the activity engages all of our senses. Getting out into a wild space and locking in on a special bird can, when all goes well, elicit a moment of total absorption that both energizes and calms us. But what happens when such a singular focus can prove hazardous to a birder’s health?

We’ve all heard stories of unfortunate birding encounters with perilous flora, fauna, and even terrain. Even the most paranoid of us can sometimes forget that wilderness is, well, wild. I made exactly this mistake when I was in Colombia this summer, yet the most shameful part was that the hazard wasn’t technically wild.

There we were descending the utterly spectacular Cerro Montezuma, from which we greeted the dawn by spotting Rufous Spinetail, Chestnut-bellied Flowerpiercer, and Munchique Wood-Wren. As the morning went on, we slipped into an easy routine of walking, driving, and ticking off amazing birds along this remote road, utterly free from contact with anyone else. This bubble of contentment must have dulled my typically sharp urban wariness, because I thought nothing of the teenager traveling up the path with an untethered cow.

Who worries about a cow, right? Well, we Bronx boys are naturally suspcious of livestock, for reasons I still don’t understand. Plus, this cow, which was apparently going to be lunch at the military base atop Montezuma Peak, was one of those lean, long-horned Criollo types so common in Central and South America. But the cow’s driver seemed to be managing well enough, so after a brief glance, I turned my eyes back to the foliage. Big mistake!

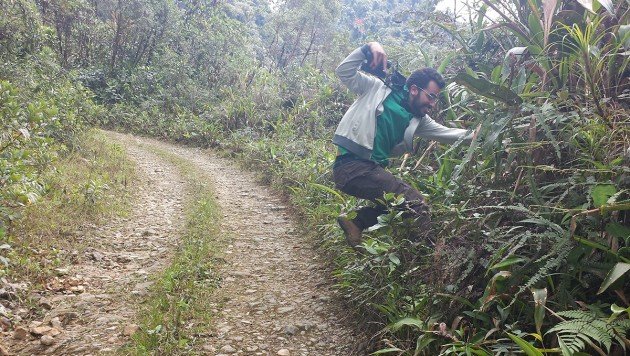

Imagine this scenario: six birders walking roughly single file down a steep mountain road, a sheer wall of rock to one side and a precipitous drop demarcated by a row of brush on the other. When, as I was obliviously scanning the trees, I heard a shout, “It’s charging!” I instinctively jumped to the side closest to me. That this happened to be the precipice of the peak mattered not at all.

Almost all of us made the same split-second choice, except for Dawn Hewitt of Bird Watcher’s Digest, who threw herself flat against the cliff. Thus, she was able to see the bezerk bovine charge our hapless group, literally galloping off the path to come within mere inches of us. In just a moment, the cow was gone, stampeding up the trail with scattered birders and a sheepish tender in its wake.

Luckily, nobody was hurt, and once the moment passed, we roundly agreed that the mad cow attack was one of the most memorable parts of our press trip. In fact, Juan Pablo Gaviria Muñoz, our fun-loving friend from Proexport Colombia, thoughtfully created a reenactment of the encounter from the perspective of the cow:

As they say, all’s well that ends well, at least as far as we were concerned. That poor kid, on the other hand, had a miserable day chasing a cow that decided the life of a fugitive beat feeding the military. We last saw that badass cow being chased by soldiers and its unfortunate handler. Still, I’ve learned my lesson and will, at least part of the time, keep my eyes forward while birding.

What’s the most memorable hazard you’ve faced on the birding trail?

Mike, between your account and the re-enactment photos I’m laughing out loud! People don’t realize the hazards of birding.

Ha ha! Off hand, I guess mine might be almost stepping on a five foot long Fer-de-Lance. That kind of freaked me out.

Mine was human. While birding near Pueblo, CO, several years ago, we found ourselves surrounded by police. “Everybody in the car put both hands out the window!” We complied. ” We have a report of suspicious activity. What are you doing?” Watching birds. “Do you realize you are watching birds next to a chemical weapons storage area?” No. “Did you notice the man with the rifle on his hood watching you?” No, pretty much focused on the awesomeness of our first ever yellow-headed blackbird. “Why are you driving a car with Florida plates when you have Ohio licenses?” Rental. “May we search your vehicle?” Have at it. After a half hour of questioning and searching we were sent on our way with the deputy’s card and instructions to call him if were going to be in the area so a call to police would not elicit such a response. I told him there was a report of a mountain plover on a road I knew went near a government facility. He called ahead to warn the, of the strangers with scopes and gave us the card of the wildlife officer. If we didn’t find one, he would know where we could find one. He then thanked us for being so polite and cooperative. I responded, “You mean we have a choice?” He replied, ” You have no idea. You have no idea.”

I still have the scar from mine.

Well, there was that time when the birds themselves tried to kill me

http://10000birds.com/sometimes-you-get-the-bird.htm

Almost stepped on a pygmy rattler that felt like curling up right in the middle of the trail a few weeks ago. If it wasn’t for the lighting storm that got my eyes out of the trees, while I rushed back to the trail head, I might have a few less toes. Oh yeah, I was barefoot due to a nice mud puddle (that I somehow didn’t notice) that soaked my shoes earlier. I now own water shoes. Thanks lightning storm!

Well, several people have already picked snakes, so I won’t go for the cobra on Java 6 feet next to me.

I guess the most tense moment during a bird walk was standing on top of a mountain, being the single highest point within an area of at least 20 km in diametre, in the middle of an intense thunder storm with lightning all around me so close I barely managed to count to “one” between the lightning bolts and the thunder claps. It is a remarkable feeling to think you may be dead before you finish the thought that you may die now.