The second edition of the National Geographic Complete Birds of North America, 2nd Edition has one of the longest book names in bird bookdom: National Geographic Complete Birds of North America, 2nd Edition: Now Covering More Than 1,000 Species With the Most-Detailed Information Found in a Single Volume. It is also, the cover tells us, “fully revised and updated,” and “companion to National Geographic to the Field Guide to the Birds of North America.” National Geographic clearly wants us to know where their newest title (to be published this week) stands in the crowded field of North American birding guides and handbooks. And, it is a wonderful book to look at, each page chock full of species facts, drawings, and range maps, organized in a design style that makes finding that exact thing you want to know easy, and that makes browsing fun. Still, looking at this book, 744 pages long, 10 inches high and almost 2 inches wide, and looking at my crowded bookshelves and the piles of books stacked next to them, I have to wonder: Is the content worth the space?

Well, to start off, we can look at the numbers. National Geographic guides are known for their exhaustively complete coverage of North American resident, migrant, vagrant, accidental, and established exotic species, sometimes even including species that have not made it to the continent yet (a Common Scoter is bound to show up soon). This volume is no exception. As the title tells us, the book covers over 1,000 species, an increase of the 962 species covered in the first edition (2005) and the 990 species in the 6th edition of the National Geographic to the Field Guide to the Birds of North America. Twelve family accounts have been added. It is 72 pages longer than the first edition. An undisclosed number of family and species accounts have been updated. Over 70 range maps were updated. (This represents an update of the range maps from the 6th edition of the Field Guide, which were used for this book, not the first edition. Doing these comparisons can get a little confusing.)

The three mainstays of National Geographic’s birding books editorial team are responsible for the book as a whole–Jonathan Adlerfer as main editor, Jon L. Dunn as associate editor, Paul Lehman as mapmaker extraordinaire. In addition, 25 contributing authors are listed, including Jon L. Dunn, Jessie H. Barry, Edward S. Brinkley, Cameron D. Cox, Donna L. Dittmann, Ted Floyd, Kimball L. Garrett, Paul Hess, Steve N. G. Howell, Alvaro Jaramillo, Brian Sullivan, Clay Taylor, and other names familiar to birders. It is noted on the “Contributors” page that most of these authors wrote entries for the first edition, and that new species and family accounts were written by Brinkley, Garrett and Hess, with additional updating of first edition accounts by the editors. Twenty-one artists contributed art for the book, including Jonathan Alderfer, Michael O’Brien, John P. O’Neill, John Schmitt, Thomas R. Schultz, and Sophie Webb, with Alderfer, Schmitt, and Schultz contributing the new illustrations for this edition. Nine photographers contributed most of the photographs used to illustrate the family sections, including Richard Crossley, Kevin T. Karlson, and Brian E. Small.

This is a large cast of contributors. The overall look of the guide is uniform and seamless, directed towards its goal of providing “in-depth” information on the identification of “all species of wild birds reliably recorded in North America”. The brief, concise Introduction lays out the format of the book and its entries. Birds are presented by family, genus, and species, following the taxonomic order of the American Ornithological Union (as of August 2013),

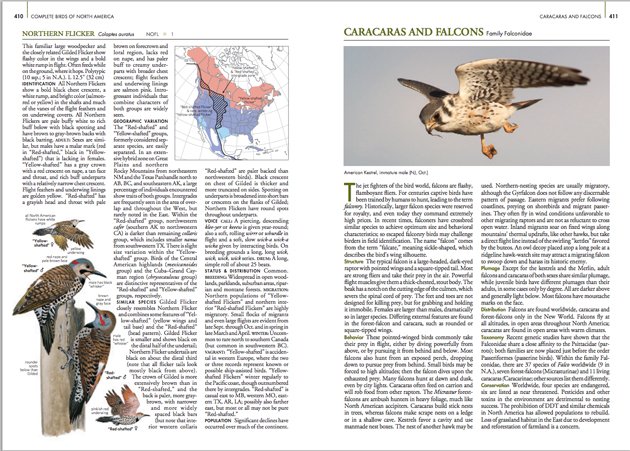

Each of the 89 families is described by an essay that details distinctive characteristics, addressing structure, behavior, plumage, distribution, taxonomy, and conservation. This is where the photograph appears, a representative member of the family. So, for the Caracaras and Falcons family (photograph, American Kestrel), we learn, amongst other things, that the feet and toes of falcons “are not designed for killing prey, but for grabbing and holding it immobile”, that eastern migrants will “often fly in wind conditions unfavorable to other migrating raptors,” that recent research has shown a close relationship with the parrot family, and that four species of this family are endangered. If there is an aspect of the book that reflects author personality, it is these family accounts. They range from encyclopedic listings of facts to loving portraits, like the Falcon essay, which sets its tone with its definition of falcons as “the jet fighters of the bird world.” The first edition gave author credit for each essay. The editors explain that they didn’t think this was appropriate here, since most of these essays have been edited and updated by other authors, but you can find the names of the original authors in the biographical briefs in the back of the book.

Genus is addressed briefly, where knowing the characteristics of a genus aids in identification. In the Hummingbird chapter, for example, descriptions are given for four out of fourteen genera, describing the structural, plumage, and behavioral characteristics that define the group. The visual design of the book helps the taxonomically challenged (which I think includes most of us) with gray bars that mark divisions and contain the scientific genera names.

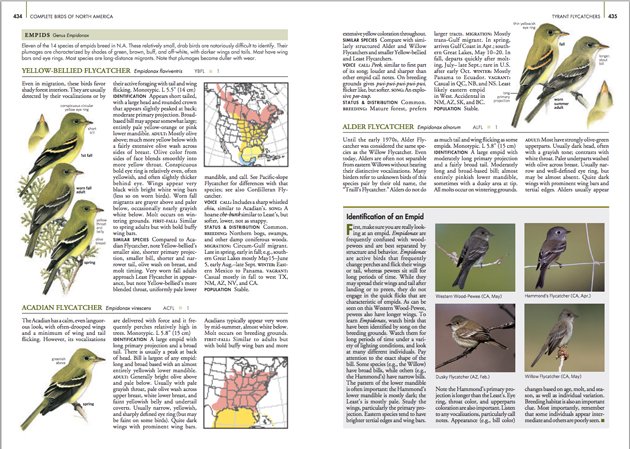

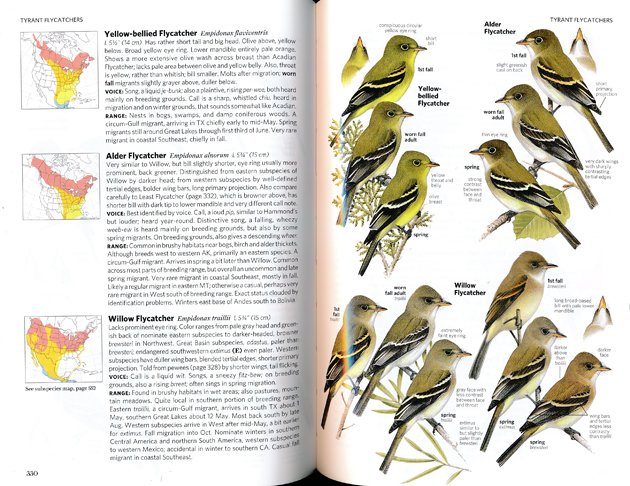

Now we come to the heart of the book, the species accounts. Time for a case study! How do the species accounts here differ from the species accounts in the 6th edition of the National Geographic Field Guide? I’m using Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Empidomax flaviventris, as my case study. Why? Empidomax flycatcher species present identification questions to beginner and experienced birders. Personally, I really do need to learn more about this species, which is not common in the NY/NJ area. And, unlike Western Empid species, it appears on a page layout that also includes this very nice sidebar on the Identification of an Empid. The illustration above is the species account for Yellow-bellied Flycatcher in the National Geographic Complete Birds of North America, 2nd edition. The illustration below is the species account for the bird in the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, 6th edition.

The illustrations, of 1st fall, worn fall, and spring birds, are exactly the same, down to the identification notes and the close-up of the under-throat. The range map is the same (as noted above, the maps in the Complete guide are taken from the 6th edition of the Field Guide, updated where necessary). The placement is different, with the illustrations, range map, and species text all of one piece, like an encyclopedia article. Most notably, the text in the Complete Birds guide greatly expands on the Field Guide text.

Field Guide text: common name, scientific name, measurements, diagnostic field marks, Voice description, Range description.

Complete Birds of North America text: Common name, scientific name, banding code, ABA classification, brief overall description, Identification (field marks for adult, worn fall adults, first fall adults), Similar Species (how to distinguish the bird from other Empids), Voice (totally different transliterations from the field guide here), Status & Distribution (breeding, migration, winter, vagrant), Population.

The Complete Birds information is framed within the family essay for Tyrant Flycatchers and the genera description for Empids; altogether this presents a description of Yellow-bellied Flycatcher and its relationship to other birds very useful for identification purposes and a little bit more. The article is less comprehensive than the scientifically based article in the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds of North America, Online. It is far more specific than The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior, where Yellow-bellied Flycatcher largely subsumed in the chapter on Tyrant Flycatchers. Let’s call it a field-guide-plus treatment.

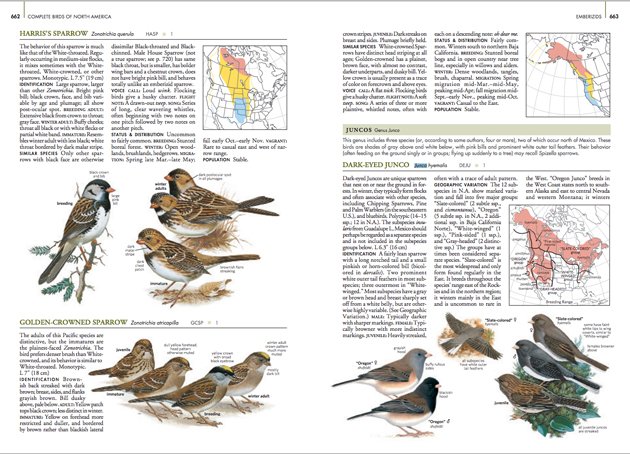

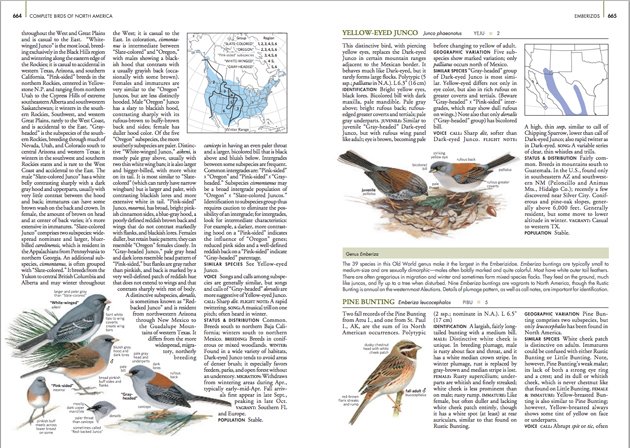

The length of each species account varies according to the identification challenge of each bird, the content varying according to the necessity of describing molts, morphs, subspecies, and other geographic variations. Accounts for many of the gull species are a full page long, Herring Gull is a page and a half. Probably, no other bird guide does geographic variation as well as National Geographic, and this can be seen in its entry on Dark-eyed Junco. The page-long entry on Geographic Variation offers descriptions of the five groups, in painstaking detail, differentiating subspecies of each group, articulating differences between males and females within each subspecies, drawing out winter and breeding ranges with the help of Lehman’s maps. If I was puzzling over a junco identification, this is the book I would consult.

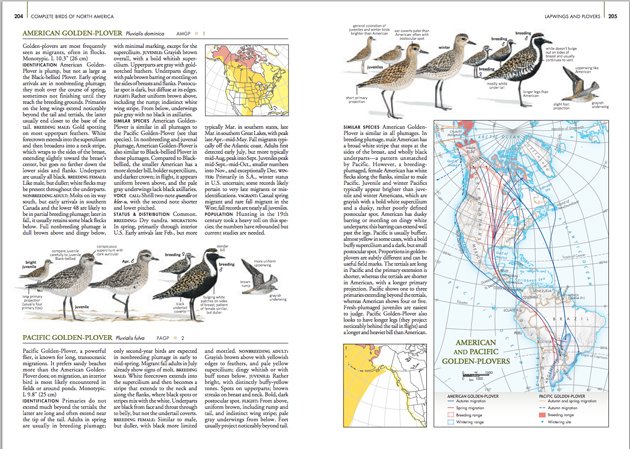

In addition to the range maps from the field guide, Lehman has also created large maps for certain species, delineating unusual or notable migrations. American and Pacific Golden-Plovers autumn and spring migrations on one map, Migration of Selected Shearwaters and Petrels, Buff-breasted and White-rumped Sandpiper autumn and spring migrations–these are three examples of a feature that might make this book worth the shelf space (and price) for some birders.

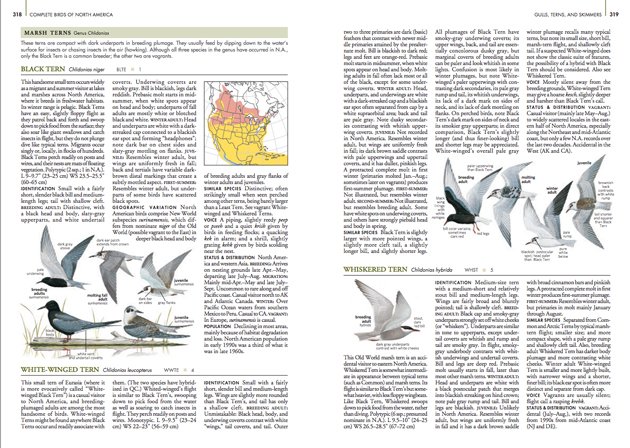

National Geographic is also known for its coverage of accidental species. In the field guide, these are relegated to the Appendix. Here, they are integrated with other species, making it easier to compare what you think might be a Whiskered Tern to the two other marsh tern species. Accounts are more extensive than in the field guide. In the case of the Whiskered Tern, we go from four lines to a lengthy physical description of breeding adult, winter adult, juvenile and first summer and distinguishing traits that differentiate the bird from other terns. A nice feature is that entries for accidental species include date and place of sightings, though of course in the case of Whiskered Tern that doesn’t include the third sighting in Cape May this past month.

Beginning and intermediate birders will find the sidebars, gray-colored text-and-photograph boxes focused on specific identification issues, helpful reading. They cover common identification questions (Separating Black-capped and Carolina Chickadees) and questions you haven’t thought about yet but find really interesting to think about for the future (Variation in the White-breasted Nuthatch). There are also min-tutorials on subjects such as Calidris Plumage and Structural Details (that’s sandpiper id) and Large White-headed Gull Basics.

Back-of-the-book material includes Additional Reading, credits for each illustration, Index, and brief biographies of Contributors. I really like the Additional Reading list, which offers selected general titles and titles of the best books on specific bird families. Also, most importantly, it makes the point that in order to be current, birders need to read online sources and mailing lists. (Yes, we know this, but it is not always reflected in bibliographies and reading lists.) I do wish its list of websites was longer, but it does happily include the ABA portal page to listservs, and indicates which web sources are fee-based.

The 13-page Index lists species by common and scientific name, as well as families and selected genera. The sidebars and large migration maps are not indexed (nor listed in the Table of Contents, which is purely by family). However, a species reference in a sidebar is indexed. In other words, if you look up Cattle Egret, you will find a reference to its species account and its inclusion in the box on Identification of White Egrets.

The National Geographic Complete Birds of North America, 2nd Edition is a book that makes good on its promises. It is encyclopedic in scope and comprehensive in its detailing of information required for up-to-date, accurate bird identification in North America. It does not have the scientific references or research knowledge offered by some other bird handbooks, and it doesn’t pretend to be that type of book. It is a one-stop source for birders who need tools for identification beyond the field guide in the backpack, and it does this extremely well. Is it worth the shelf space? If you enjoy learning about the birds you see and hope to see and, sadly can’t see anymore (because it does include extinct birds), and if you want to learn quickly, from top birding experts (which doesn’t mean you don’t want to read a book about a specific bird family, you just don’t have the time right this very minute), then this is the right, the appropriate book. Now, excuse me, I’m off to figure out which titles need to be jettisoned from my bird-guide-shelf to make room for National Geographic Complete. I might just have to invest in more shelving.

—————

National Geographic Complete Birds of North America, 2nd Edition: Now Covering More Than 1,000 Species With the Most-Detailed Information Found in a Single Volume,

Edited by Jonathan Alderfer, with Jon L. Dunn, maps by Paul Lehman

National Geographic Society, October 2014.

ISBN-10: 1426213735; ISBN-13: 9781426213731

744pages; 10.1 x 7.2 x 1.8 inches

$40.00 (available at a discount from the usual suspects)

Thank you to National Geographic for providing a review copy and a pdf version, which made it easy to create the graphics for this review.

Leave a Comment