Last month woodpeckers, this month penguins. Some are cute, some are dignified (and royal!). None fly, most are curious and social, which probably contributes to our cultural perception of penguins as one step away from human. They are software mascots, cartoon characters, animated film dancers, children’s book heroes, zoo celebrities, and documentary film stars. Penguins are also bellweathers of climate change; dwellers of remote areas you’ve (probably) never heard of; creatures who have developed unique, innovative ways of adapting to the harsh environments where they breed and rear chicks and the water environments in which they feed and swim. As much as you think you know about penguins, there’s a lot more to learn and wonder at, and it’s all in this book, Penguins: The Ultimate Guide by Tui De Roy, Mark Jones and Julie Cornthwaite.

King Penguins heading out to feed, Macquarie Island (beginning of book)

This is not your ordinary reference book, though it was cited as one of the best reference sources of 2014 by Library Journal. Nor is it your usual beautiful-images-but-no-substance coffee table book, though the photographs are amongst the most stunning I’ve ever seen. The contents are a balance of the visual, the factual, and a form of participant-observation, oriented towards people who know little about penguin habitats, life cycles and conservation issues.

There are three parts: (1) Life Between Worlds by Tui De Roy–personal accounts of the photographer’s journey to the breeding grounds of the 18 species that make up the Penguin family, profusely and beautifully illustrated; (2) Science and Conservation, edited by Mark Jones—16 articles on scientific advances being made in diverse areas of penguin-focused research and an article by Jones on Penguins in popular culture; (3) Species Natural History by Julie Cornthwaite—Species Profiles and additional cool Penguin facts and demographics.

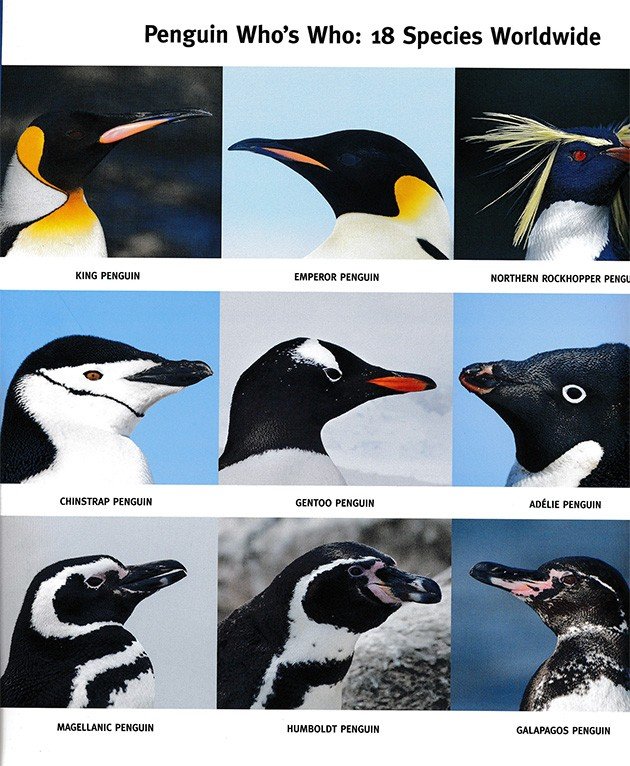

Every section is excellent, . Going from back to front, the Species Natural History section is where to go for answers to all your questions about penguins and then some. The introductory Penguin Who’s Who introduces each species visually. This is the page spread to use if you need to figure out the different black-and-white patterns of Magellanic, Humboldt, Galapagos, and African Penguins. The 4-page Fascinating Penguin Facts is a fun read, feeding us lay people scientific goodies like how penguins’ flippers are really wings with flattened and rigidly joined bones, the exuberance of penguin courtship displays (all species), and their vulnerability to oil spills, which destroys their feather weatherproofing (ultimately killing them). I found the 2-page chart on Penguin Range and Population Status, based primarily on Birdlife International Species fact sheets, very useful while reading this book; it’s a quick reference to genus, species names, range and breeding sites, population estimates, and threats.

The Species Profiles list alternative names, where the species was first described, taxonomic source and notes on subspecies, name origin conservation status, and status justification. And that’s just the top section! Detailed information is given for physical description and coloration, size and weight, voice (including contact and courtship calls, juvenile whistles, and various grunts), population and distribution, breeding (habitat, social aspects, courtship, nest, laying, incubation, chick rearing, fledging), food, and principal threats. Eight to eleven photographs illustrate each two-page species account, and a map shows breeding sites and population strongholds.

This section ends with a wonderful idea–a guide to Where to See Wild Penguins. The reality is that it’s if pretty difficult to see most penguin species, excepting the wonderfully accessible African Penguins at Boulders Beach outside Cape Town, South Africa and the Galapagos Penguins, ironically one of the rarest and most commonly seen species. But, if you are determined to see more, this section will tell you what countries and islands to target, the best seasons, and web sites for expeditions and refuges. Once you read Tui de Roy’s section, you will understand why the words “patience, flexibility and a sense of adventure are a must” are an understatement.

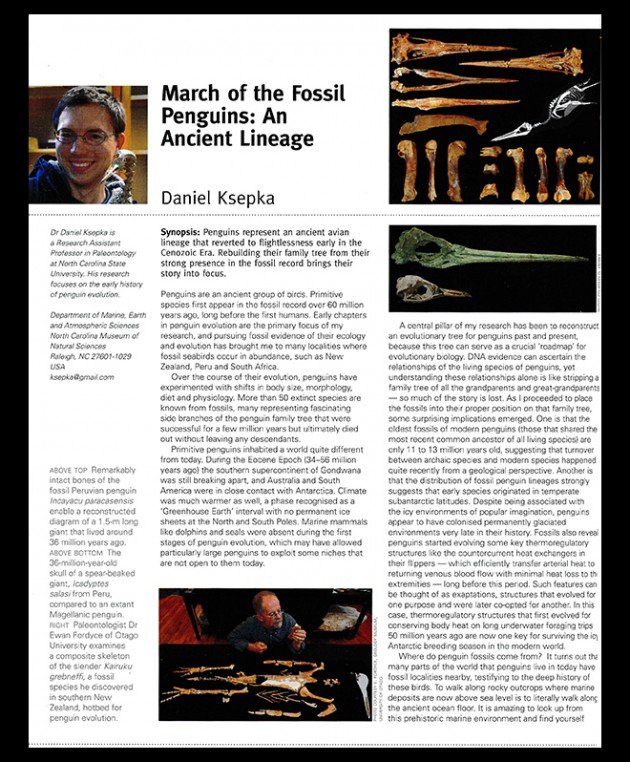

Science and Conservation, the second section, presents two-page summaries of the diverse research being done around the world about penguins. The studies range from reconstructing the penguin evolutionary tree from fossil bones to development of technology for tracking penguin movements underwater to surprising discoveries about the character and function of penguin coloration to an analysis of how Little Blue Penguins recovered from the crash of the sardine stocks in Australia.

The vulnerability of penguin species to climate change is a constant in almost every article; it affects their food sources, breeding cycles, exposure to disease. On the positive side, penguins have evidenced survivor instincts for coping. One of those instincts might be said to include the way they have, with their cuteness and their ability to make us smile, embedded themselves into cultures around the world. Jones’ essay Penguins and People: A Retrospective offers a lengthy in-depth history of this relationship, teasing out explorers’ confusion of penguins with alcids (especially the Great Auk), tracing a change in attitude from ‘skin them for profit’ to ‘let’s base every other animated film on them’. Our attachment to these creatures probably accounts for the number of research projects on their lives; we fund what we like.

The first section, Life Between Two Worlds by Tui De Roy is the heart of the book. De Roy is an incredibly accomplished wildlife photographer, writer and conservation advocate with a fascinating personal history; she gives us little glimpses of throughout her essays, and left me wanting to know more. Raised in the Galapagos, she’s been exposed to penguins her whole life. She’s produced seven photographic books about the Galapagos Islands and books on the Andes, Antarctica, and New Zealand (her current home). Penguins was preceded by Albatross: Their World, Their Ways (2008), co-authored with Mark Jones and Julian Fritter; the Penguins book was conceived with Jones and Cornthwaite as a successor to Albatross. (Its title in the Great Britain and New Zealand editions is Penguins: Their World, Their Ways, a better title in my opinion.)

Magenellic Penguin, parent and child. (p. 28)

De Roy observed and photographed Penguin colonies for a 15-year period to create this book. She traveled to Antarctica and South Georgia, East Antarctica and the Ross Sea (“deep Antarctica”), Patagonia, the Falkland Islands, the small desert islands off the coast of Chile, the Galapagos, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia, and Tristan da Cunha and Gough Islands in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean. She was accompanied on some of these journeys by Jones and Cornthwaite, and she did some journeys on her own, notably a six-week expedition on an Australian icebreaker to photograph Emperor Penguins in the spring. These were not easy journeys, and we can only guess how much time was spent making contacts and raising funds to go to the ends of the earth or the middle of nowhere, where the penguins live. The emphasis is on the natural observations and the joy that trumps all inconvenience and crazy weather and weeks of waiting.

De Roy writes her essays about each penguin species from a very personal point of view. She talks about the experience of photographing these creatures; the serene happiness of sitting motionless as Gentoo Penguin chicks gently pull at her clothes, the unearthly joy that overcomes the weariness of staying up all night to photograph Little Blue “fairy” Penguins, or the wonder of spying an Emperor Penguin colony in the middle of a vast ice shelf from a helicopter. There is also a great deal of biological and ecological information encapsulated within De Roy’s experiences. She relates her first-hand observations of how the penguins move from sea to land and then back again; what the penguins sound like as they socialize and mate and fight; what the islands look like when filled with the penguins and how they deal, if at all, with predators. She also describes the larger life cycle of each species and how, if more than one species occupies the same area, they co-exist.

Adélie Penguins on iceberg, South Orkney Islands (p. 51)

The text is of a whole with the photographs, which are simply magnificent in content and presentation. The color quality is outstanding; each page was obviously designed with care, balancing image and text, and, in some cases, given totally over to an image that will communicate, as no description can, the way penguins live. The photographs illustrate every detail of the life of every species and place their lives in the context of their habitat, reminding us that as much as we associate penguins with snow and ice, many of them breed on isolated, rocky or brushy or lava-created islands and coasts.

Northern Rockhopper, Gough Island (p. 97)

There are over 400 photographic images in Penguins: The Ultimate Guide. The book does not list who took which photograph, it states that all photographs are by the authors unless otherwise indicated. An interesting way of presenting images resulting from a group project; one that makes us think about the subject rather than the creator. I like it, but I also feel frustrated by it. I like to know the stories behind the images. I like to know WHO created images that make me pause and consider traveling to Antarctica. Fortunately, the authors’ website, Roving Tortoise Photos, gives attribution for 55 photos from this book, so I can say that all three authors are indeed incredible photographers.

Cornell University Library’s online catalog, which includes the holdings of the Adelson Library of the Laboratory of Ornithology, lists 72 titles on penguins in its collection; two are in Russian, two in French, six are juvenile titles, and 2 are books on organizational change. There are additional penguin titles not listed in the catalog, like photographer/writer Wayne Lynch’s Penguins of the World (Firefly, 2007). That’s a lot of books about a bird family that cannot fly. Still, I can’t believe that there is a penguin book out there that has images more beautiful and content of as much breadth as Penguins: The Ultimate Guide. It is a book that inspires awe and concern and, at least for me, an intense desire to travel to remote rocky regions populated by crazy looking birds. It is not an essential purchase. It is one that can be shared with friends and family (who does not adore penguins?), and used for travel of the soul. I dream of traveling to the Subantarctic Islands of Australia and New Zealand ; I’m very happy that Tui De Roy, Mark Jones, and Julie Cornthwaite were actually able to make the trip.

—————-

Penguins: The Ultimate Guide

by Tui De Roy, Mark Jones & Julie Cornthwaite

Princeton University Press, Sept. 2014.

240p.; 9 x 12; hardcover: $35.00

ISBN: 9780691162997

(Also available under the title Penguins: Their World, Their Ways from

Bateman Publishing, New Zealand and Christopher Helm, London)

Ticked my first penguins ever a few weeks ago – African Penguin – at a colony near Cape Town, South Africa.