The danger of reviewing a field guide to the birds of an exotic country you’ve never been to is that you become obsessed with visiting that country, no matter how far away and how expensive it may be. So, when Redgannet asked me if I was interested in reviewing Phillipps’ Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo: Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei and Kalimantan, Third Edition, by Quentin Phillipps and Karen Phillipps, a book he had acquired at Birdfair, I hesitated. Did I dare dip my toe into this catalog of tantalizing species? With a trip to South Africa on the horizon at the time, I thought I could handle it. Now, I’m not so sure. I’m already looking up birding tours of Borneo and pricing airfares.

Borneo is the third largest island in the world; politically it is divided amongst three countries–Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), Indonesia (Kalimantan) and the sultanate of Brunei. It is humid and hot, with some areas receiving between 150 and 200 inches of rain each year. Not a great place for a family vacation. Well, my family. As Duncan relates, it can be a fun place even for nonbirders. And if you are a birder, consider this–combined with a geography of lowland and montane rainforests, seashores and rivers, mountain ranges culminating in Mt. Kinabalu (at 13,455 feet the highest peak in southeast Asia), and human development that has resulted in freshwater rice fields, secondary forest, and oil palm plantations, Borneo offers an incredibly high degree of biodiversity. Phillipps’ Field Guide (I’ll be using this shortened form of the title) covers 673 avian species, including 59 endemics, and 53 species that have not been documented yet for the area but which may show up in the next few years. Borneo, the authors say, is under-birded. I think we need to do something about that.

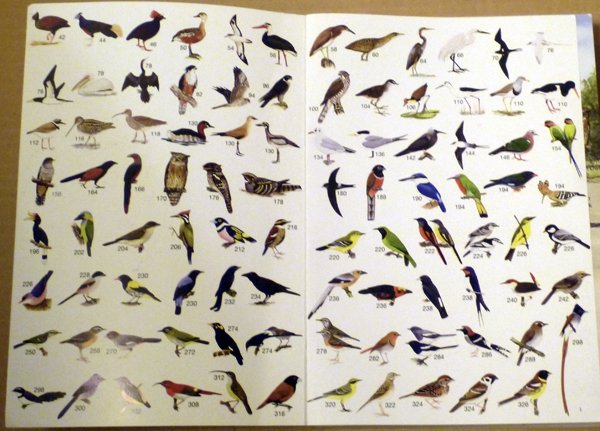

The field guide differentiates itself from other guides to birds of Borneo and Southeast Asia (Birds of Borneo: Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak, and Kalimantan by Susan Myers (Princeton Univ. Press), which Mike reviewed in 2009, is the one most people will be comparing it to), by a view of birds that encompasses their habitat and ecology. This is evident in the introductory material, which includes sections on The Origin and Evolution of Borneo’s Birds, Conservation in Action, Vegetation and Bird Life in Borneo, Climate, Rainfall and Bird Breeding Seasons, and Bird Migration. It also features, in addition to an image index on the inside front cover (see above), Graphic Indexes to seven specific habitat areas–Birds of The Seashore, Coastal Gardens, Padi Fields, Rivers and Streams, Lowland Forest, Kinabalu Park HQ, Kinabalu Summit Trail. The Indexes show images of the most common birds of the area against a painted background, with page references to species accounts.

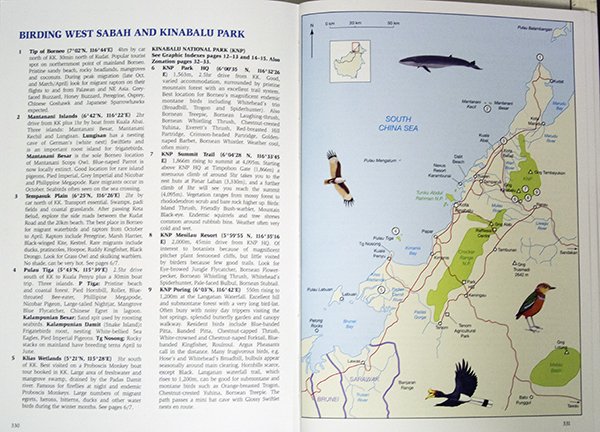

Bookending these indexes, the back of the book features 11 guides to birding in the most bird-rich areas of the island. There are two-page spreads with a list of birding sites, map coordinates, and bird descriptions on the left and full-page maps on the right, showing roads and routes linking the sites. Nothing wets the appetite for a birding trip like a map with a Blue-banded Pitta posed in the middle and a Rhinoceros Hornbill flying across the edge!

The authors, Quentin Phillipps and Karen Phillipps, are siblings who grew up in Sabah, the birdy part (well, most often birded part) of Borneo. Quentin won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition (junior section) with the first-ever photograph of a nesting Chest-nutheaded Thrush. He also started contributing papers to Sabah ornithological journals as a young man, and has been a part of Bornean ornithology ever since. Karen studied graphic design in London and has illustrated a number of books on Asian birds, plants, and wildlife, including the mammoth A Field Guide to the Birds of China (co-authored with John MacKinnon, Oxford Univ. Press, 2000) and the earlier The Birds of Hong Kong and South China (co-authored with Clive Viney and Lam Chiu Ying, Hong Kong Information Office, 2005). She currently lives in the Algarve, Portugal and Quentin splits his time between London and Sabah, according to the brief biographies in the back of the book. We are all familiar with couples who write field guides together, but this is the first time that I’ve encountered a brother and sister team. I’m always curious about how books are written, and I’m hoping that at one point in the evolution of this guide, they include a section on sibling birding and sibling writing.

Back to the field guide! Species Accounts are grouped by family, following what appears to be Sibley and Monroe’s 1996 taxonomy. (I couldn’t find an explanation of the organization in the introductory material; if I missed anything, let me know in the comments.) So, we start with Megapodes (scrubfowl), Pheasants, and Partridges, then on to Ducks. Organization within families is oriented towards user convenience rather than a strict taxonomy; for example, Ducks are divided into Resident Ducks and Migrant Ducks, Bulbuls are divided into Bulbuls and Bulbuls of the Hills and Mountains.

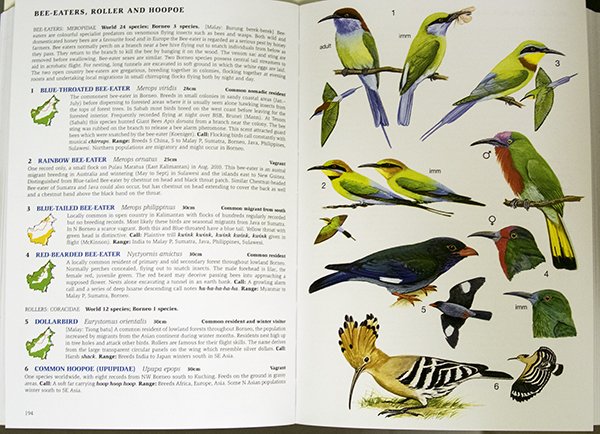

Each significant family is described briefly—scientific name, number of world species, number of Southeast Asia species, number of Borneo species, number of endemics, characteristics that unify the family with an emphasis on behavior, habitat, nests, and calls. This is great, background material, especially if you are unfamiliar with the birds of Southeast Asia. The family descriptions reflect a fascination with these birds that goes beyond simple expertise, commenting that “how Imperial Pigeons survive on a purely fruit diet is a mystery,” delineating the “ventriloquial quality” of the Barbet’s call. I do wish that a way of distinguishing pages with family descriptions had been incorporated into the design of the field guide, maybe a colored tab or graphic symbol. It is hard to distinguish these pages, and I found myself squinting to find the full-capped but non-bolded scientific names that start most, (but not all) of these paragraphs.

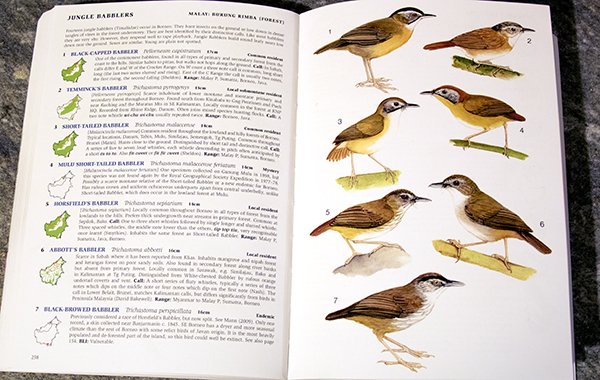

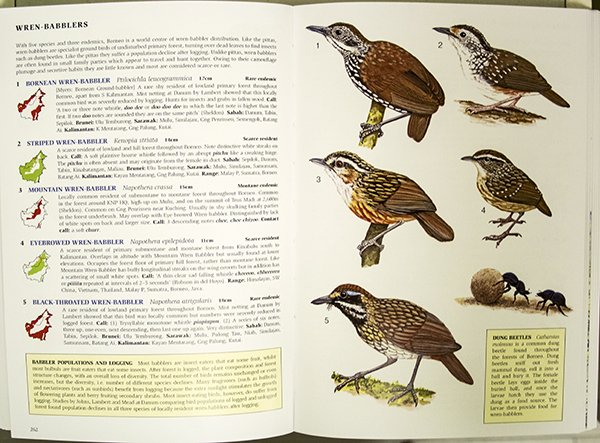

Species are presented in what is becoming a classic field guide style– two-page layouts with text and thumbnail distribution maps on the left, drawings on the right. Bird images are numbered to correspond with the text. So, if you’re not up on your babblers, you need to do a little head swiveling to differentiate images of Temminck’s, Short-tailed, Mulu Short-tailed, Horsfield’s, and Abbott’s Babbler from each other. I didn’t mind doing this at home, but I can see where it might become inconvenient when you’re out in the field.

Text entries for each species start with the basics: scientific name, size, and status, ranging from “local nomadic resident” to “scarce winter visitor” to “rare endemic”. The brief description expands on the bird’s status, telling us in what area and/or habitat it is most likely to be seen, and describes details of the bird’s behavior and physical features most valuable for identification. More attention is paid to behavior and calls then to physical details; the introduction notes that users should rely on the illustrations for this purpose. Vocalizations are both transcribed and described; much of this material is footnoted, a feature I haven’t seen in other field guides. A number of the species accounts also offer alternate common or Malay names and notes on taxonomy (possible split!). The thumbnail distribution maps are colored for status (green for resident, yellow for migrant, red for endemic); country ranges of resident and migrant species are included in the text.

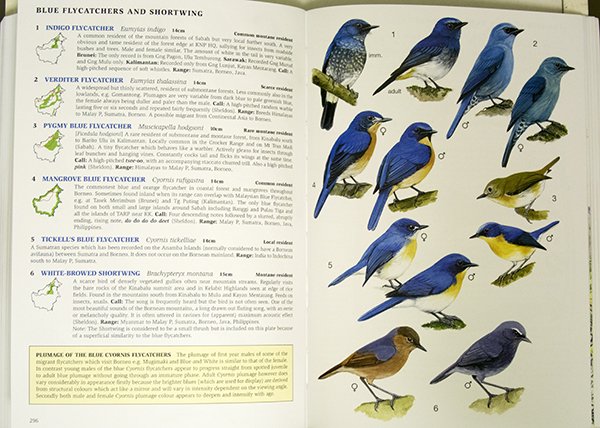

Artwork is by Karen Phillips. The plates show differing plumages as required by the individual families and species. Males and females are indicated by symbol, immature, juvenile, adult breeding, adult non-breeding indicated by abbreviations. First and second winter and summer plumages are depicted for gulls; breeding and juvenile pale and dark and intermediate morphs for Skuas. Flight images are included for raptors, gulls, seabirds, shorebirds, nightjars, swallows, swifts, hornbills, and to a lesser extent for other birds, though, strangely, only for the few resident ducks, not the vagrant species.

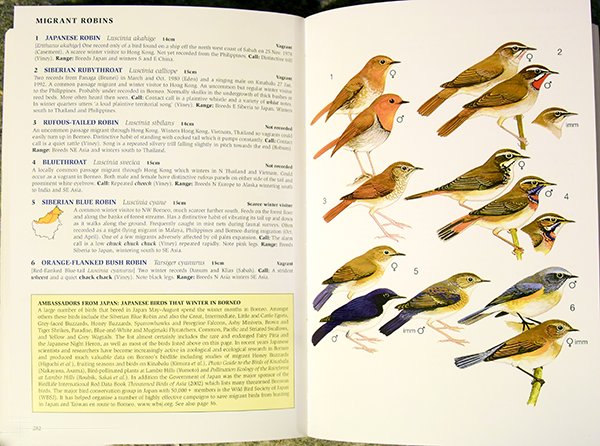

The main thing that strikes you about the artwork as you browse through this book is the diversity of plate designs. There are plates like the one for Migrant Robins, images grouped neatly by species, all facing the same direction in the same perched pose.

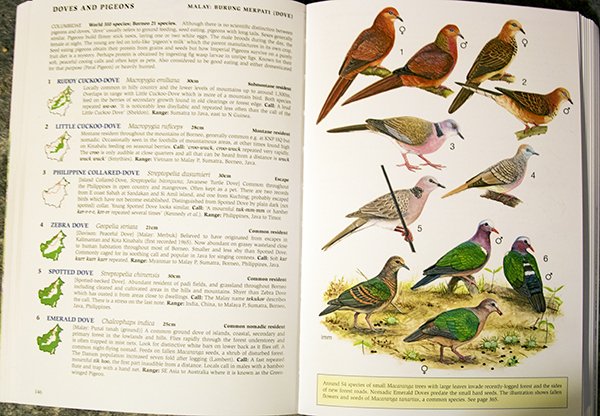

Then there are plates like those for Doves and Pigeons, with six species delightfully posed around the page, all looking towards the left, but some perched on branches, Ruddy Cuckoo-Doves sitting evenly, a Little Cuckoo-Dove tipping downward, a Spotted Dove on a diagonal wire, four Emerald Doves on the ground amidst the flowers and seeds of Macarangua tanarius, a small tree that invades recently logged forests, with a side bar explaining this part of the illustration. The uniformity of the lines of some of the more standardized plates are interrupted by behavior and botanical images–a Mountain Leaf-warbler feeding a juvenile Sunda Cuckoo; nutmeg seeds dispersed by Pied Imperial Pigeons and eaten by Nicobar Pigeons, a rare nomad; Dung Beetles rolling a ball of dung (the beetles will lay eggs into the dung which will produce larvae which will be a food source for Wren-Babblers).

Browsing this field guide is a visual pleasure. But, I couldn’t help wonder why there is such a range of illustration. A little bit of Internet digging helped me figure out that some of the plates are recycled from Phillipp’s earlier books. The plate for ‘Curlew, Whimbel, Godwit and Dowitcher’, for example, is identical to the plate for these birds in The Birds of Hong Kong and South China; the only difference is that numbers replace species names. (I do not have a copy of this book, but I was able to find sample plates on book dealer sites.) The richer, more interesting plates are recent work, reflecting Karen Phillipps development as a nature illustrator. This third edition features 15 “entirely new” plates (Falcons, Doves, Whistlers, Swallows and Martins, Wren Babblers, Warblers, Thrushes, Shamas, Forktails, Sunbirds, Ground-Cuckoo) and 16 “upgraded” plates with additional or replacement drawings.

Overall, I like the illustrations, especially the newer ones, which show greater attention to detail and a more relaxed approach. The colors are bright where there are supposed to be bright (the Pittas, Kingfishers, and Minivets shine), the rufousy-brown-gray-and-black birds are handsome, and the Frogmouths are impressive in their blunt bristly-ness. This is the point where I need to point out that I am not an expert on what these birds should look like, and am working from images drawn up from the Internet and in other books. I did notice that one of the few birds I’ve seen, Scaly-breasted Munia, is strangely drawn, the head and back lighter than the birds I’ve seen, the breast redder. I think this is an aberration and I hope it will be corrected in a future edition.

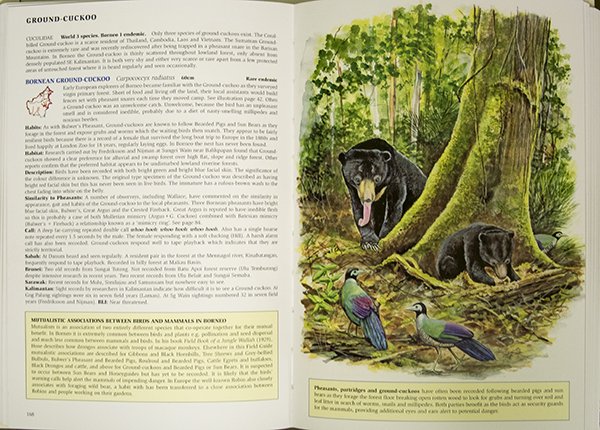

A birder traveling to Borneo will be focusing on endemics, and the authors of Phillipps’ Field Guide are well aware of this. The introductory section offers a listing of the Fifty-Nine Endemic Birds of Borneo, with common name, scientific name, ‘best location to find’, and page number of species account. (This section is misnamed in the Table of Contents, which was apparently not edited to reflect changes in the third edition.) Distribution maps for endemic species show endemic ranges in bright red, making it easy to spot them if you prefer browsing to using the endemic table. Special attention is paid to the Bornean Ground-Cuckoo, one of three ground-cuckoos species in existence, and, needless to say, a very shy and very rare bird. The two-page spread, shown above, gives a history of the species interaction with humans (fortunately, it does not taste good so it is not actively hunted) and documents records for each of the four areas covered by the guide.

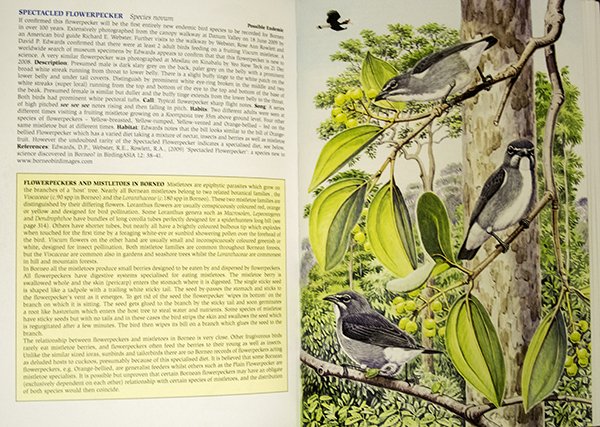

The species account section, in fact, the whole book, is full of additional material that expands our knowledge of the birds of Borneo and the world in which they live. The ‘sidebars’ are presented, for the most part, in black-outlined, yellow boxes; content ranges from the Honey Buzzard’s mimicry of Hawk-Eagle plumages (and how this benefits both species) to an appreciation of Bertram Smythies, the author of the first book on the birds of Borneo, to “Fig Tree Fruiting in Borneo,”. The latter is part of a larger section on Hornbill ecology and conservation. There are a total of 85 sidebars and informational notes and, unlike most guides that include sidebars, they are listed in their own table of contents, a section in the back of the book called List of Ecological and Text Notes. At last!

The sidebars and other extras–the Bornean Ground-Cuckoo page, the page describing the recent discovery of the Spectacled Flowerpecker, the diagram on how to distinguish a raptor mimic from a raptor model–make Phillipps’ Guide more than an identification guide. It is part identification guide, part bird finding guide, and part ecological guide. There is additional back-of-the-book material I haven’t described yet that adds to its educational utility–a lengthy Selected Bibliography and Further Reading section; a list of Useful Websites, the requisite indexes by common and scientific name, and a regional and a topographic map on the inside back cover.

The wide scope is the big difference between this book and Susan Myers’ Birds of Borneo. The Myers book is an excellent identification guide, documenting each species’ physical features in detail. The adult male Green Broadbill, for example, is described as “Iridescent bright green, tuft of feathers on forehead almost obscuring short bill, black spot on rear ear-coverts, three black bars on wings, flight feathers green edged black; iris dark brown, bill greyish-yellow, legs and feet olive-grey.” Phillipps’ Guide has no text describing the bird at all, noting simply that it is the commonest of the greenbills and mainly found in lowland forest. The illustration does show every feature articulated by Myers, plus a baby Broadbill peaking out of a hanging nest. This is the difference between the two books in a nutshell. With less introductory and ancillary material (it does include maps, a graphic index similar to the one in Phillipps’ Guide, and brief habitat descriptions), Birds of Borneo is a more compact, lighter book. In a perfect world, a birder would have the resources and the luggage room to buy and take both guides. For those of us in the world of weight allowances, the choice must be one of personal preference.

Phillipps’ Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo: Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei and Kalimantan, Third Edition, by Quentin Phillipps and Karen Phillipps is a thoughtful field guide to a magical part of the world, unique in its focus on the country as a whole rather than on individual bird identification. It promises to be particularly useful to birders who have never visited Borneo before, and to the courageous birders who would like to bird the country on their own. There are editing errors and the lack of uniformity in the way the plates are drawn and organized may bother some birders (though others may delight in the design diversity). It offers lessons to other nature authors and publishers on how we can improve the field guide as an educational tool that encourages an ecological, conservation approach to bird travel. I know that when I go to Borneo (and I’m going to get there, someday), it will be in my backpack for plane reading, with Myer’s Birds of Borneo in my suitcase. Because, when it comes to bird guides, I can’t say no.

———————————————————————-

Phillipps’ Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo: Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei ad Kalimantan, Third Edition, Fully Revised.

By Quentin Phillipps and Karen Phillipps.

372 pages, 8.3 x 5.7 x 1.1 inches, 141 full color plates, 600 distribution maps, 12 maps.

ISBN-10: 0691161674, ISBN-13: 978-0691161679

U.S.: Princeton Univ. Press, March 2014; UK: John Beaufoy Publishing Ltd; 2014.

$26.95

Thanks to Redgannet for loaning me his copy of the field guide and to Princeton University Press for providing review copies of Phillipps’ Field Guide to the Birds of Borneo and Birds of Borneo.

The assertion that Borneo is not family vacation material is ridiculous. I saw many families, some of which even seemed to be having fun.

This is very true, Duncan. I should have written Borneo is not a place where MY family would enjoy vacationing. Which says more about my folks than Borneo.

Changed that sentence up a bit, Duncan, so readers won’t get the wrong idea. I am jealous that you got to bird there.

“Borneo, the authors say, is under-birded. I think we need to do something about that.” Oh yes and I’m ready to help! However, I’m afraid that if I get that book, it will keep me from getting any work accomplished.

That book looks pretty awesome. May add it to my Wishlist.

I may have to put this one my bucket list.

Do you know a pdf edition?