Any doubt I had about the need for a book about rare birds in the United States And Canada were wiped out on a Sunday evening in early February with two birding friends. Recovering from and celebrating an excellent day of birding along the Hudson River, the conversation eventually turned, as it is apt to do when birders talk, to the more unusual birds we’ve chased and seen over the years. My friends had many more years of birding on me and had many stories to tell. And, as we talked of Long-billed Murrelets and Pink-footed Geese and Nutting’s Flycatchers, questions came up. What year was the Red-footed Falcon seen in Massachusetts? What are the chances of finding a Redwing amidst flocks of robins? What does “ship assisted” mean? Where did the Coney Island Gray-hooded Gull come from, Africa or South America?

I kept wishing I had Rare Birds of North America, by Steve N. G. Howell, Ian Lewington, and Will Russell, right in front of me. I had just started reading it, but I knew that this was the book my birding friends, in fact all North American birders who are fascinated by vagrants, have been waiting for. It is a book that embraces identification and analysis of avian rarities and vagrancy patterns throughout the United States and Canada with an enthusiasm and devotion to statistical, geographic, and ornithological detail that will both delight and challenge birders.

First, what is a rare bird? In this book, rare birds are species “for which, on average, only 5 or fewer individuals have been found annually in North America since around 1950.” In other words, migrating birds that don’t belong here but are seen here. And, not very often. Species that were once seen rarely and have now become more common, like Clay-colored Thrush, are not included. Neither are rare subspecies. But, irruptive species like Blue-footed Booby, that may in some years, as we know from the invasion of 2013, show up in numbers greater than five, are included. Interestingly, the authors also decided to include eleven species not yet accepted as occurring naturally by records committees, but which, they say, present interesting vagrancy questions.

Rare Birds of North America covers 265 species within these parameters. The authors set June/July 2011 as the cut-off date, and were able to add noteworthy records up to November 2012, the date the manuscript was sent to the publisher. New species that were documented from Fall 2011 through Summer 2012 are listed in one of the appendices. So, no, this book does not include the Rufous-necked Wood-Rail of Bosque del Apache fame. This is the problem with books, there always has to be a point where the author says, “Enough.” And, since the writing and illustration of this book took over ten years, I think we can say that the authors tried their best to put in all the birds they could. (Steve Howell’s account of how Rare Birds of North America was born, with cautions for future authors about timing and printers, can be found on the Traveling Trinovid Blog.)

There are three main parts: (1) The Introduction, a 41-page analysis and discussion of migration and vagrancy, topography and molt; (2) Species Accounts; (3) Back of the book material, which includes three appendices, Literature Cited, and Index. There is also a useful prefatory chapter on “How to Use This Book” that explains the unusual organization of the Species Accounts, as well as maps of the geographic areas—East Asia, Mexico and adjacent areas, the Caribbean and adjacent areas—discussed in the text, a glossary of advanced terms and abbreviations and a listing of abbreviations.

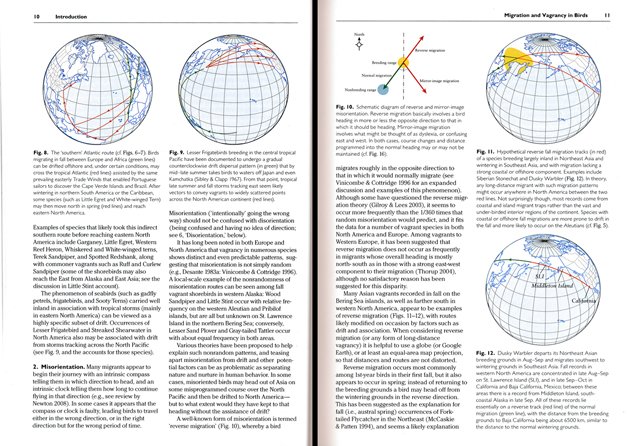

The Introduction’s sections on “Migration and Vagrancy in Birds” and “Where do North American Vagrants Come From” are the heart of the book, representing the authors’ thoughts on vagrancy patterns, based on years of experience, past ornithological research, and their own data analyses . The authors postulate six processes underlying vagrancy, and then discuss vagrancy routes from the “Old Word”, the “New Word”, and the seas (“Pelagic”). This is extremely detailed material, involving migration and vagrancy patterns, dates of the sightings that underlie these patterns, exceptions to the patterns, and a lot of geography. Observations, conclusions, and hypotheses are supported by references to scientific articles and to records from North American Birds and other sources. Lengthy tables present where and when (season) rare birds have been seen. Global maps illustrate migration routes and vagrancy routes due to processes such as drift and misorientation.

As someone who is more of a “big picture” person, I found this material daunting. I think there are many birders, however, who will eat it up. This is what we talk about when we talk about rarities, only with a lot less conjecture and a lot more informed reasoning. Reading these sections also enhances the Species Accounts that follow, providing a framework for understanding how and why each species has been seen in a particular place at a particular time.

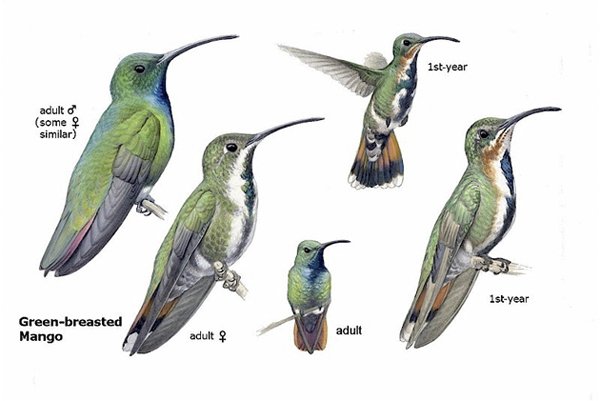

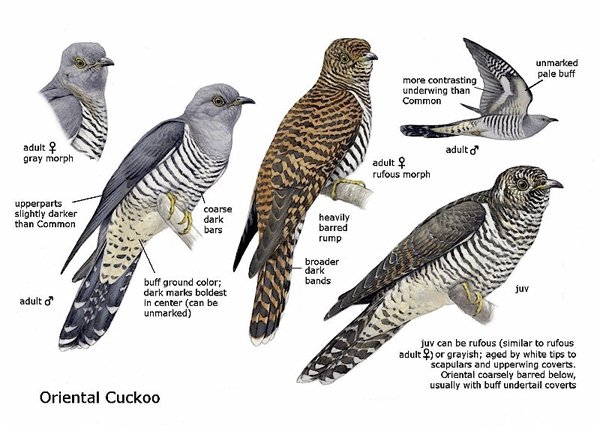

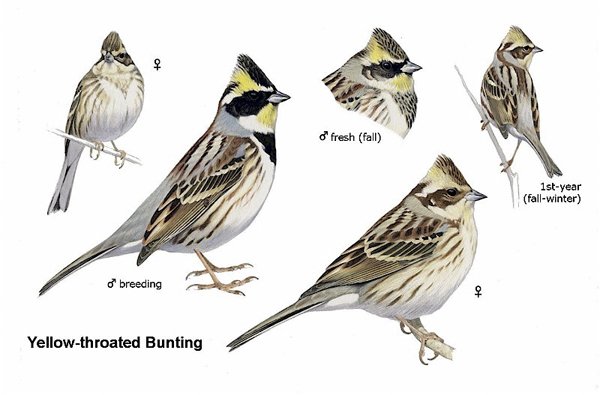

The Introduction also devotes a section to molts and plumages, an important part of identifying rare birds and their sex and age. As can be expected when one of the co-authors is the author of a book on molt, this material is also highly detailed and authoritative. This is more than an identification issue. Knowing if a specific species is “off course” when it is a first-year or an adult bird may help determine how and why the process has occurred.

The Species Accounts are arranged by types of water birds followed by types of land birds, with taxonomy once again shunned due to its ever changing nature. Within many of these groups, species are further divided into Old World and New World categories. This can be confusing. The Old World Common Cuckoo, for example, is pages away from the New World Dark-billed Cuckoo, separated by species such as Eurasian Hoopoe and Zenaida Dove. It makes sense when you understand that this is not primarily an identification guide. It is a book about patterns of vagrancy, of which identification is a part. So, every part of the book is filtered through questions of origin. It would have been helpful from the reader’s point of view, however, if each general section (Shorebirds, Wading Birds, etc.) started with a listing of species in the order presented. It’s hard to shake the browsing habit.

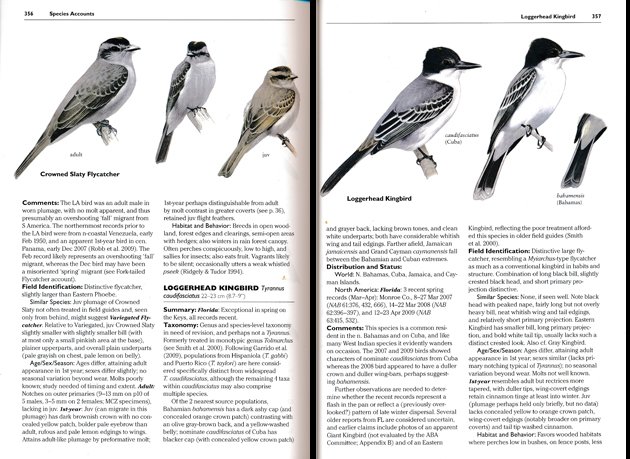

Each Species Account gives the common and scientific names of the bird, measurements, text and illustrations. The text starts with a Summary of where and when the bird has been documented and is then divided into sections on Taxonomy, Distribution and Status, Comments, and Field Identification (material on Similar Species, descriptions of molts and plumages by Age/Sex/Season, and Habit and Behavior). Accounts are thorough and detailed; rare sightings of the bird are cited, dates and locations are given for single sightings. So, yes, here is the March 2007 record of the first Loggerhead Kingbird that I saw in Key West and there is the second record of Greater Sand Plover, a bird I saw on Little Talbot Island, Florida in May 2009. (I won’t apologize for the brags, we all know this is a part of our birding culture, and I only allow myself a certain number of brags a year.)

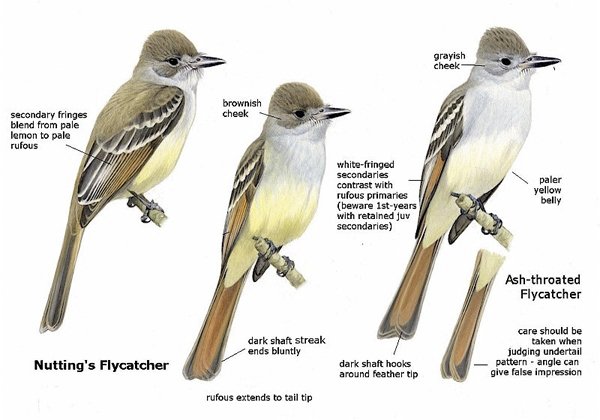

I like the the attention paid in the illustrations and text to differentiating similar species. Greater Sand Plover, for example, is illustrated, next to Lesser Sand Plover, with a long paragraph on how to differentiate the two. Similarly, the distinction between Little Egret and Snowy Egret is spelled out visually and in a long section that details differences in legs and bills and lores for adult, juvenile, courting, and nesting birds. This is valuable material. As much as recent field guides have tried to include more vagrant birds, there just isn’t enough space for the kind of detailed comparisons provided here.

The Comments sections are analyses of the species’ vagrancy pattern, the answer to pull out when someone asks you, “But, why is there a Fieldfare in Massachusetts?” Though, as the authors make clear, there is often no certainty to the postulated reasons why the bird is where it does not belong, and some of the Comments sections can make your head spin with the multiple different processes proposed for birds sighted in fall and spring, in the east and in the west. This is an important section to read, though. As the authors state in the prefatory chapter, “If we have anything original to say, it probably appears in this section.”

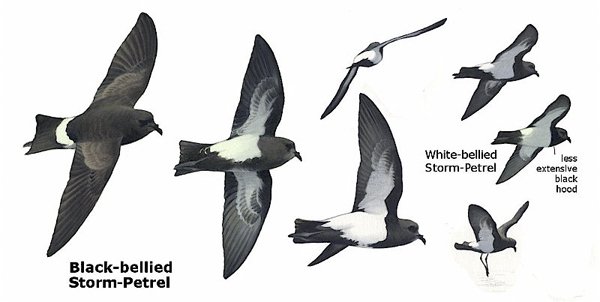

The illustrations are by Ian Lewington, a British bird artist and birder who has co-authored or contributed to a number of nature books, including Rare Birds of Britain and Europe. They are, as you can see, both beautiful and functional, depicting important identification features and presenting multiple images of a bird in a way that does not sacrifice information for design. There is a plate for each species, depicting plumages likely to be seen in North America. Birds are also shown in flight, or from the back or in a head close-up, whatever is required for identification.

The other two co-authors of Rare Birds of North America, Steve N. G. Howell and Will Russell, are well known in the U.S. birding community, though Howell did come over from Cardiff, Wales. Howell has written a number of books, including Petrels, Albatrosses, and Storm-Petrels of North America: A Photographic Guide, the Peterson Reference Guide to Molt in North American Birds, and A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America (with Sophie Webb). He has led birding tours for many years and is a research associate at Point Blue Conservation Science. Will Russell is a founder and managing director of WINGS, now “semi-retired.” According to Howell’s blog article, Russell has had a longstanding interest in bird migration and vagrancy, and is credited with the original conception for the book.

The authors enthusiasm for rare birds is reflected in the back of the book material, which includes three appendices, two of which update the book: Species New to North America, Fall 2011-Summer 2012; Species of Hypothetical Occurrence; and Birds New to North America, 1950-2011. The 35-page bibliography of “Literature Cited,” is probably the best compilation you could find of literature on the topic of rare and vagrant birds in the United States and Canada. I do have a problem with the Index. I like the fact that it lists topics (“austral migration”, “reverse migration”) as well as bird species (common names only). I am disappointed that the page listings for species do not print the page numbers for species accounts in bold print. If I am looking for the species account for La Sagra’s Flycatcher, for example, I need to guess if it’s on page 30 (not likely), 343, 350, or 408. This is a case where having the book in digital format can be a big plus.

Rare Birds of North America is available in hardcover and in digital format. I’ve used the iBook version on my iPad and MacBook, and I love it. The book on the screen looks exactly as it does in paper; the colors of the plates are reproduced in all their brilliance, the pages ‘turn’ as if you were reading a physical book (or you can opt to scroll down), and there are the added advantages of being able to link from the index directly to the wanted page and back again. I particularly enjoy reading the book on my iPad, where I can enlarge, enjoy, and study the illustrations. I have discovered one error: the table of contents doesn’t list species accounts past “Raptors and Owls.” It’s odd. There is a better and complete table of contents within the eBook, but it is hidden (link to “Copyright”, then turn the page).

The need for a table of contents is minimal in an eBook, however. All you need to do is use the Search function to find the bird or topic you need. Which is one of the things I love about using the book this way. Another advantage is the convenience of having Rare Birds on your iPad, in your backpack, ready to whip out the next time you’re trying to turn that Wilson’s Shearwater into a Black-bellied Storm-Petrel. Or simply discussing vagrants you’ve known and loved with friends. A word of caution: not all digital books are the same. Rare Birds of North America is available in a number of digital formats (see their online catalog for the list), part of Princeton University Press’s new eBook initiative. The usability and convenience of the eBook will vary depending on the platform.

Rare Birds of North America is a significant addition to our birding literature. It gives the advanced birder the tools with which to identify vagrant birds. It gives the analytic birder facts and ideas about migration and vagrancy, some of which may be familiar, some new, some original. I do wish that the authors had written more about why it is so important to know about bird vagrancy. What does it mean in the larger sense? Is research on patterns of occurrence contributing to a larger body of knowledge that will in turn help us recognize environmental threats? Or, is this research for its own sake, aimed at helping us understand a tiny bit of the unknowable? We are fascinated by rare birds. The mystery of their presence makes finding one, chasing one, viewing one a unique experience. It is good to have a book that synthesizes the past, so we can intelligently discuss the rare birds of the future.

———————————

Rare Birds of North America

by Steve N. G. Howell, Ian Lewington and Will Russell

Princeton University Press, Feb. 2014

448 pp. | 7 x 9 1/2 | 275 color plates. 2 line illus. 9 tables. 17 maps

$35.00 retail

ISBN: 9780691117966

eBook | ISBN: 9781400848072 |

eBook available in Kindle, iBook, Nook and other formats. See PUP web page for full list.

Birds make the environment more loving to the community.We should recognize their presence.I love music,and for that matter i thank God for the gift of mocking birds.