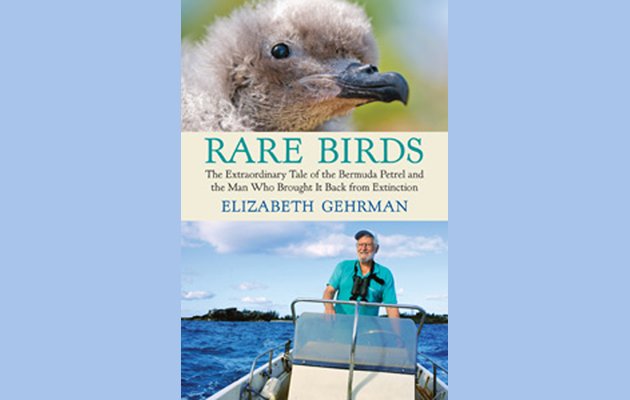

The cahow is one wild and crazy bird. Born in a burrow, it first sees daylight when it is time to fledge, and then spends years at sea, flying, flying, flying with speed and acrobatic agility on thin wings that may take it thousands of miles from its birthplace, till it is time to come home to Bermuda to mate. There, it courts at night, the less moonlight and the wilder the winds, the better. And, all the while it vocalizes with the strange-sounding, weird cries that give the bird its name, cries so bizarre sounding that they once kept Spanish explorers from settling the island. What? You’ve never heard of the cahow? It isn’t in your book of seabirds? (It certainly isn’t in MS Word’s dictionary, because my draft is full of red underlining every time I type it.) Try Bermuda Petrel, Pterodroma cahow, one of the group of seabirds called gadfly petrels. But, to Elizabeth Gehrman, the author of Rare Birds: The Extraordinary Tale of the Bermuda Petrel and the Man who Brought it Back from Extinction, and to David Wingate, the man who Gehrman profiles in this excellent book, the Bermuda Petrel is always the cahow.

The story of the cahow, a “Lazurus species” that was thought to be extinct for over 300 years and then discovered to be breeding on a tiny remote island in Bermuda, is part of modern birding legend. In addition to Gehrman’s book, two films have been made about the cahow and David Wingate within the past ten years—Rare Bird, a documentary directed by Lucinda Spurling, and Bermuda’s Treasure Island, directed by Éamon De Buitléar. Articles on the Bermuda petrel have appeared in scientific journals and popular birding magazines, and Wingate has been the subject of articles in the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and has received the Linnaean Society’s of New York prestigious Eisenmann medal.

But, it’s a new story to me, one that reads like a fairy tale. In brief, it goes like this: In 1951 Robert Cushman Murphy, of the American Museum of Natural History, and Louis S. Mowbray, director of the Bermuda Aquarium, embark on a quest to locate the cahow. The bird, which was once so plentiful that it was a major food source for English settlers and sailors, captured in the hundreds, was believed to have been extinct since 1620, but there were enticing hints and clues– stories told amongst Portuguese fisherman, a live bird found in 1906 by Louis L. Mowbray, the father of Louis S., other birds that collided with a tower and a radio antenna. The men take along 15-year old David Wingate, who already had a local reputation for his knowledge of birds (in fact his nickname was “Bird”). In Castle Harbour, on a small rocky island, the men and boy find a deep burrow and in the burrow they find a bird. After much work because the burrow is deep and narrow, the bird is pulled out of the burrow, and Murphy says, “By gad, the cahow!” Wingate looks at the bird and knows he has a calling. He will bring back the cahow. And, like a good fairy tale, there is a happy ending.

So, this is a tale of two rare birds, the Bermuda petrel and David Wingate. It’s hard to say which is the more fascinating, and Gehrman gives attention to both. She chronicles the history of the cahow, from its first mention in the diaries and letters of the Spanish and British men who explored and sailed away and explored and settled the islands of Bermuda, to its destruction and seeming extinction by the forces that always seem to be at work on island ecological systems—invasive mammals such as pigs, dogs, and cats; rats; loss of habitat due to settlement and overuse of native resources; and, due to loss of habitat, competition for breeding burrows with the other bird of Bermuda, the more aggressive White-tailed Tropicbird (known in Bermuda as the longtail). She places the cahow’s tale within the larger story of how Bermuda’s endemic plants and wildlife, especially the Bermuda Cedar, were exploited and replaced with invasives that caused more destruction. And, in a very lovely section in the middle of the book, she describes the life cycle of the cahow, informing evocative passages about their nocturnal courtship and flight with recent research findings about how seabirds are able to function—eat, sleep, navigate home. It is hypothesized, for example, that nocturnal seabirds like the Bermuda Petrel eat bioluminescent prey.

Wingate’s story is interwoven with the tale of the cahow in the first part of the book, but his life and personality take over much of the later chapters. Called variously a “free spirit,” an “unguided missile,” a “nut,” and a “genuine eccentric” by the friends and colleagues Gehrman interviews, he is clearly opinionated, independent, and brilliant. If he were 40 years younger (he will be 78 years old on October 11th), some cable channel would be building a reality show around him. Wingate had one of those great childhoods in which he explored Bermuda’s islands day and night, on land and on water, using a homemade boat. His focus on birds is so obsessive, it’s surprising to find out that he left Bermuda to attend college at Cornell, and, that he fell in love, married three times and brought up (sort of) three daughters. Gehrman approaches Wingate’s personal life with sensitivity. One of the best chapters of the book, for me, describes his life with Anita, his true love and first wife, and their early-married life on Nonsuch Island, at the time a barren isolated place with no electricity or plumbing. Later, there were magic summers on the island with their children, friends, and friends’ children (and the various animals Wingate was always taking in), and the terrible accident that resulted in Anita’s early death. This very personal story might seem out of place in a bird book. It isn’t, because it is a part of the whole life of this exceptional man.

Much of Wingate’s professional life revolved around his grand plan to create a “living museum” of pre-colonial Bermuda flora and fauna on Nonsuch Island, a habitat where the cahows would be protected and supported. The tiny islands on which the birds were found breeding in 1951 could not support them much longer, and Wingate also discovered that the longtails were predating on cahow chicks. Wingate decided that the birds needed Bermuda’s ecology as it was 300 years ago, and he was going to create it for them. This is how he ended up living on Nonsuch, an island on which every tree had been felled, all grass eaten by goats, which had formerly been home to a yellow fever hospital and a reform school. Over decades, and largely by himself, Wingate, transformed Nonsuch, first as a side project while working for the government, and then as Bermuda’s first conservation officer. This was a gigantic project, way beyond just creating ways to protect cahow burrows from longtails (which Wingate also did, by creating baffles), and Gehrman takes us through many of Wingate’s struggles to bring back trees and mollusks and turtles and herons and fresh water pond life that no longer existed in Bermuda. The stories illustrate the pitfalls of ecological conservation; every new life form brought to Bermuda impacted its ecology in some unanticipated way. A particularly good type of fertilizer, for example, drastically increased the population of crabs, spoiling Bermuda’s golf courses.

Ultimately, the story always comes back to the cahows, whose population grows slowly. In addition to longtails and rats, Wingate battles developers (of course), a rare Snowy Owl that kills 5% of the cahow population (Wingate shoots the owl, to the dismay of many), and the U.S. military, whose base is directly across from Nonsuch and who seems to be continually in engaging in projects, like building a new ball field, that will impact the birds. Wingate cannot battle DDT when it starts affecting the cahow eggs, but he can provide scientific evidence that is included in the landmark suit that results in its banning. All the while, he is observing, documenting, practically living with the cahows when they return to Bermuda. He has no need to band them, because he can distinguish one bird from the other by behavior and feathers. His connection with the cahows may seem obsessive, but it results in the accumulation of a large body of knowledge about the bird and its life cycle on land, without which the species would not have been saved. He also mentors young conservationists, including Jeremy Madeiros, his successor as conservation officer. Madeiros engages in practices Wingate dis not initially approve of, like translocating cahow chicks to artificial burrows on Nonsuch (Wingate thinks this is intrusive, that the birds should be allowed to come to the island on their own). But, Madeiros is clearly continuing Wingate’s work. In 1951, there were 18 breeding pairs of cahows discovered on three tiny islands. Today, there are 105 breeding pairs, 12 of them on Nonsuch (these numbers are from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Neotropical Birds web site).

Elizabeth Gehrman, a journalist who has contributed to the Boston Globe, first encountered Madeiros and a cahow chick named Somers (the first cahow chick born on Nonsuch Island in 400 years) while on assignment to write about Bermuda for a travel magazine. She has done an excellent job researching both the history of the cahow and of David Wingate, using historical primary sources for the first and interviews with Wingate’s colleagues, friends, and family for the second. In addition, she has David Wingate himself, both in interviews and in writing–personal diaries and professional unpublished manuscripts. She uses both sources well. Wingate’s expressive voice, enthusiastic when talking about his cahows, other times outraged or rueful or nostalgic, flavors Gehrman’s prose, turning her reporting into a unique, personal story. Yet, Gehrman never allows Wingate’s point of view to prevail, and carefully balances his views on certain topics, particularly his forced retirement at the age of 65 from his government appointment and resulting expulsion from his government home on Nonsuch Island, with opinions from others. She has also done an incredible job organizing what must have been an explosion of highly detailed information about Wingate’s projects into a well-structured book

Elizabeth Gehrman, a journalist who has contributed to the Boston Globe, first encountered Madeiros and a cahow chick named Somers (the first cahow chick born on Nonsuch Island in 400 years) while on assignment to write about Bermuda for a travel magazine. She has done an excellent job researching both the history of the cahow and of David Wingate, using historical primary sources for the first and interviews with Wingate’s colleagues, friends, and family for the second. In addition, she has David Wingate himself, both in interviews and in writing–personal diaries and professional unpublished manuscripts. She uses both sources well. Wingate’s expressive voice, enthusiastic when talking about his cahows, other times outraged or rueful or nostalgic, flavors Gehrman’s prose, turning her reporting into a unique, personal story. Yet, Gehrman never allows Wingate’s point of view to prevail, and carefully balances his views on certain topics, particularly his forced retirement at the age of 65 from his government appointment and resulting expulsion from his government home on Nonsuch Island, with opinions from others. She has also done an incredible job organizing what must have been an explosion of highly detailed information about Wingate’s projects into a well-structured book

Gehrman begins and ends the book with trips with Wingate to see the cahows, at sea in the beginning, on Nonsuch at the end. These are magical experiences. The fate of the Bermuda Petrel, the cahow, is still in question. The species is still considered endangered, and the increasingly ferocious hurricanes resulting from climate change are posing a new threat to their breeding grounds. Yet, the book, buoyed by the energy and spirit of David Wingate, leaves one with a feeling of optimism. This is a good read, informative and engaging. Highly recommended for birders and naturalists in need of a good environmental real life fairy tale, complete with eccentric prince.

—————-

photo of Elizabeth Gehrman: Ingrid Skousgard, 2012.

Rare Birds: The Extraordinary Tale of the Bermuda Petrel and the Man Who Brought It Back from Extinction

by Elizabeth Gehrman

Beacon Press, 2012.

Hardcover, 256 pages. $26.95.

Kindle edition available.

ISBN-10: 0807010766: ISBN-13: 978-0807010761

The man and the mission sound not only fascinating, but inspirational, Donna. Thanks so very much for bringing this book to our attention. Preservation and conservation is never an easy row to hoe, and it requires such tremendous sacrifices when you find yourself in the position of being a ‘Lone Ranger’ while others are viewing you as a ‘Don Quixote’. But success is its own sweet reward and vindication. And it sounds as though Wingate remarkably achieved that hard-won victory for the cahow – and himself.

Have you perchance read Kathleen Kaska’s book, The Man Who Saved The Whooping Crane? http://operationmigration.org/InTheField/2013/06/04/the-man-who-saved-the-whooping-crane/ Kathleen does a wonderful job of weaving Robert Porter Allen’s ‘Indiana Jones’ lifestyle into the story of whooping crane conservation in North America. There is no question that without the intrepid Bob Allen our tallest American bird would no longer exist, as they were down to 15 in number when he fortuitously intervened. Now numbering nearly 600 (only 270 of which are in the wild flock) after 60 years, the bird still has a long way to go to become conservationally stabilized, and is under increasing threat from new sources. I highly recommend this book, too, as a riveting birding adventure tale.

I definitely need to read Kaska’s book, Carrie. You’re right, Wingate and Allen are inspirational, and I probably should have emphasized that more in my review. I find myself both inspired and intimidated by their lives, because these “rare birds” accomplish their goals at the expense of their relationships and other parts of their lives.