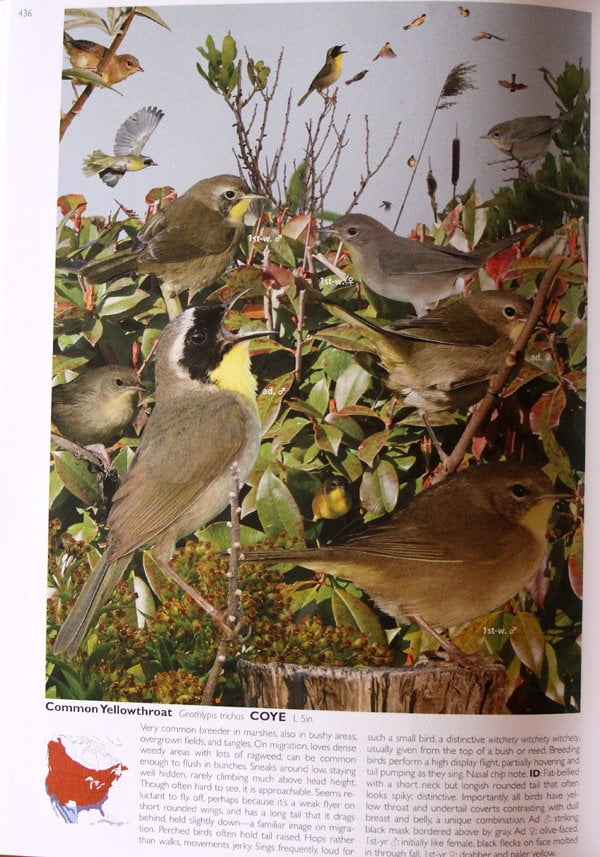

The Crossley ID Guide from Princeton University Press has long been anticipated and has certainly been the subject of many discussions among birders across North America. Now that it is in the hands of reviewers across the country we can see that it is unlike any other field guide we have ever seen. It is larger, has more images, and a completely  different approach than Sibley or Peterson or Stokes or Kaufman or any other field guide to birds. Each plate is a photoshopped piece of habitat populated by a single species seen from multiple angles and distances. For example, the Common Yellowthroat plate has thick brush in the colors of early autumn as the habitat. An adult male bird sings in the left foreground while a first-winter male stands in profile in the right foreground. A little further back in the well-photoshopped scene are female birds, both adult and first-winter, and another first-winter male. There are eight different flight shots in the background, including shots of the male’s display flight, something I have never seen, and other shots showing the front and back of yellowthroats in typical perched postures. Altogether, on the one plate devoted to Geothylpis trichas, there are at least eighteen different photographs of the species, to say nothing of a range map, descriptions of both behavior and appearance, and the four-letter code for the bird, COYE.* Is my description not enough? Well, as Richard Crossley, the gregarious and not-very-shy author of this guide says in his introduction, “A picture says 1000 words!” which is why the plate is reproduced at left (and if you click it you can get a bigger view).

different approach than Sibley or Peterson or Stokes or Kaufman or any other field guide to birds. Each plate is a photoshopped piece of habitat populated by a single species seen from multiple angles and distances. For example, the Common Yellowthroat plate has thick brush in the colors of early autumn as the habitat. An adult male bird sings in the left foreground while a first-winter male stands in profile in the right foreground. A little further back in the well-photoshopped scene are female birds, both adult and first-winter, and another first-winter male. There are eight different flight shots in the background, including shots of the male’s display flight, something I have never seen, and other shots showing the front and back of yellowthroats in typical perched postures. Altogether, on the one plate devoted to Geothylpis trichas, there are at least eighteen different photographs of the species, to say nothing of a range map, descriptions of both behavior and appearance, and the four-letter code for the bird, COYE.* Is my description not enough? Well, as Richard Crossley, the gregarious and not-very-shy author of this guide says in his introduction, “A picture says 1000 words!” which is why the plate is reproduced at left (and if you click it you can get a bigger view).

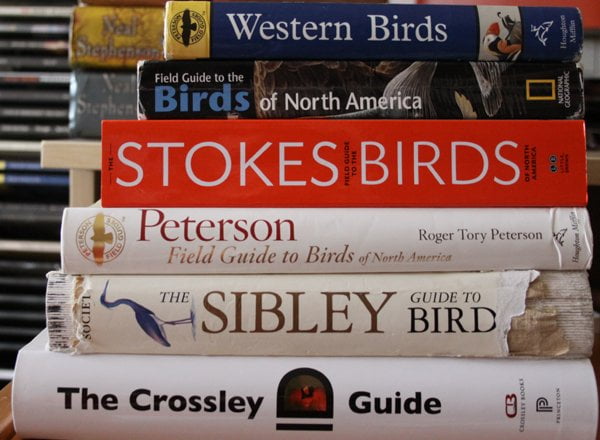

Before I go further into the content of the book I have to talk about the 800-pound gorilla in the room. Well, maybe 800-pounds is a little bit of an exaggeration but not by that much. The Crossley ID Guide Eastern Birds is HUGE! It is by far the largest field guide for North American birds that I have encountered and it only covers half of the continent. It is taller, deeper, and as thick as what must be considered the golden standard of North American field guides, Sibley, and Sibley covers the whole of North America (and is itself reluctantly lugged out into the field by buff birders, though the eastern and western volumes of his guides are much easier to carry). This makes it highly unlikely that Crossley will ever be used for what is the ostensible purpose of a field guide, which is identifying birds in the field. This may be why it is called an “ID Guide” rather than a field guide.

The Crossley ID Guide stacked up with Sibley, Peterson, Stokes, NatGeo, and Peterson West (that last one was included as a representative of the “normal” size for eastern or western guides)

If The Crossley ID Guide is not going to be used as a field guide in the field, for what purpose can the purchaser of this book use it? Crossley tells us in his introduction:

…the principal reason for its design is to be interactive with the reader — much like a workbook at school.

When looking at a plate for the first time, try to view it without any preconceived ideas — just an open mind. Simply ask yourself: ‘What do I see?’ Be careful that you do not look at it based on any preconceived notions of ‘What am I supposed to see.’ In particular, look at the smaller images in the background, because the chances are that this is what you will actually see in real life. By zooming in and out of the bird images, try to absorb the things that remain constant–shape, patterns of color, and so forth. If you can create a good mental image of these patterns, it will serve you well in the field.

Oh, so we’ve been given homework in our “workbooks” have we? Every birder can certainly stand to study more images  of birds and no matter how much you know there is always more to learn. But looking at little tiny static images (and the ones in the background can be positively minuscule) is, in this reviewer’s opinion, of minimum value. Beginning birders need to be out in the field looking at birds to get their gestalt. They will not get it from field guides or ID guides no matter how many images there are. Expert birders already know the gestalt of most birds they are likely to encounter and are dealing with the absurdly difficult identifications like differentiating empid flycatchers, a task for which Crossley’s book does little more than any other North American field guide. This leaves the birders in the middle, a category in which I include myself. What do we get from Crossley?

of birds and no matter how much you know there is always more to learn. But looking at little tiny static images (and the ones in the background can be positively minuscule) is, in this reviewer’s opinion, of minimum value. Beginning birders need to be out in the field looking at birds to get their gestalt. They will not get it from field guides or ID guides no matter how many images there are. Expert birders already know the gestalt of most birds they are likely to encounter and are dealing with the absurdly difficult identifications like differentiating empid flycatchers, a task for which Crossley’s book does little more than any other North American field guide. This leaves the birders in the middle, a category in which I include myself. What do we get from Crossley?

What I think the birder that is between novice and expert gets is the most valuable aspect of this book: the sheer number of pictures of each species from multiple angles. For example, this past weekend while birding with a bunch of birders we flushed an Ammodramus sparrow that we were sure was a Seaside Sparrow but we only got a back view as it flew weakly over the marsh away from us.  Looking at Crossley’s book (when we got back to the car, I am not inviting a hernia by carrying that thing), which includes an image of a Seaside Sparrow flying away from the observer, confirmed our impression. Lots of images of birds from many angles, in many poses and in flight, are always useful and not having to search all over the internet to find the image you need is great. I think this is of limited value to a novice, however, who is more likely to get a fleeting glimpse of a bird and then page through Crossley until they find an image “just like the bird I saw” which may or may not be remotely like the bird that they actually saw.

Looking at Crossley’s book (when we got back to the car, I am not inviting a hernia by carrying that thing), which includes an image of a Seaside Sparrow flying away from the observer, confirmed our impression. Lots of images of birds from many angles, in many poses and in flight, are always useful and not having to search all over the internet to find the image you need is great. I think this is of limited value to a novice, however, who is more likely to get a fleeting glimpse of a bird and then page through Crossley until they find an image “just like the bird I saw” which may or may not be remotely like the bird that they actually saw.

Of course, there is more to this book than just the utility of it. Some of the plates are simply gorgeous. The Summer Tanager plate, the Loggerhead Shrike plate, and the Common Loon plate all stand out to me for some reason, probably because Crossley catches the feel of their habitat very well. The shorebird plates are all well-illustrated with a huge number of images which is only to be expected from one of the coauthors of The Shorebird Guide. The raptor plates are excellent as well, with the many flight shots of each bird showing how variable an appearance raptors can have. Sometimes the attempts at making a pretty plate are too over the top, like in the two plates that feature a rainbow in the background. Should we use the presence or absence of leprechauns as a field mark? Despite the occasional rainbow the plates are largely a success aesthetically and serve their purpose of showing each species in many plumages from many angles.

I have one final criticism of The Crossley ID Guide and that is that it seems to have been put out a bit too hastily. Blank pages between sections, mislabeling “Saltmarsh Sparrow” as “Sharp-tailed Sparrow” and including a family of Mallards on the Cinnamon Teal plate are all problems that should have been caught and addressed prior to publication. No project this size is ever perfect but all of those errors were eminently catchable. The good news is that there is a web site for all things related to this book and it includes a page where errors are corrected. Make sure to check out Crossley Books for more information.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I like The Crossley ID Guide and I think it is absolutely awesome that someone has come up with a new way of presenting bird images in a guide format. But I don’t think that it knocks Sibley from the top spot among North American field guides. It is a great reference, a beautiful book, and I strongly recommend that birders buy a copy as it is well worth the $35.00 cover price (already available for $21.00 at Amazon).

…

Everyone has been reviewing this book! Read more reviews of The Crossley ID Guide in the bird blog-o-sphere on Nature Remains, The Birdchaser, Steve Blain, Another Bird Blog, The Urban Birder, The Birder’s Library, Ivory-Bills Live, and Avian Review. If you have reviewed The Crossley ID Guide as well and I missed it please leave your link in the comments.

…

Book Information from Princeton University Press

Cloth Flexibound | 2011 | $35.00 / £24.95

544 pp. | 7-1/2 x 10 | 10,000 color images.

e-Book | 2011 | $35.00 | ISBN: 978-1-4008-3923-0

…

*I am not a big fan of the four-letter codes. Sure, they are a nice shorthand and using them means that more text can be fit onto each page, but they are also a barrier to entry for novices who have a hard enough time learning common names (and whose energy would be better spent learning the much-more-useful scientific names rather than four-letter codes). Seriously, other than being shorter what value do the four-letter codes have? None. Well, actually, as we learned at the Superbowl of Birding, it is fun to call someone a “Crossley 493!”

…

I keep hearing people talking about how beautiful the images in the crossley guide are, but to be honest, whenever I see pictures of the plates, it just looks cluttered and muddled. I don’t quite understand the fascination with this book. Maybe I need to hold it in my hands to understand…

@jmj: They are undoubtedly cluttered. Some are more aesthetically pleasing than others, but they are definitely instructive. Reading the intro and seeing it for yourself will give you a much better idea of what Crossley was trying to accomplish.

@Cory: I think you might rather hear “Crossley 493!” on a big day attempt than “I had too much Crossley 46 for breakfast, and now I have to go to the Crossley 257”.

I haven’t done a complete review, but posted these preliminary impressions on Valentine’s Day:

http://somewhereinnj.blogspot.com/2011/02/whats-not-to-love-about-this-man.html

Bought mine yesterday. It is definitely a good compliment to a collection of guides, but Sibley will continue to live in my car…not David himself, but his book. Crossley would never be the book I’d go to first. I’ll do an ID in the field or on the road with Sibley, then confirm it with any number of guides at home. I found the plates in Crossley jarring and cluttered at first, but after just leafing through the book for an hour tonight, I’ve come to like them. The habitat shots really do capture the feel of the place.

Had it in my hands today for the first time.

1. I love the idea of many views of the same species, different plumages, flight, standing, etc. More pictures / less words definitely has its place.

2. However, immediately had to put it down … the pretty background was totally distracting. Hummingbird? Nope, it seemed like a page of pictures of flowers. A rainbow on another page?

This guide might be better suited to people who are less distractable than me.

One thing I love about this guide is how it’s forcing all of us to re-evaluate what we expect from an ID guide. Crossley and Princeton U Press really have introduced something new.

I’ve been processing the guide for a few days. Thumbing through the sparrow plates, I realized how powerful some of Crossley’s background choices are. Spotting Bachman’s Sparrow in its pine-palmetto habitat sets that species apart from all the other little brown jobs. He might not have hit the mark every time, but thanks to this guide, I now understand certain sparrows a bit better, which I hope will lead to more satisfying encounters in the field.

I agree with Mike that Crossely has produced a book that does something new. It doesn’t replace other books like Kaufman, Sibley, or Nat Geo, it attempts to portray the bird as you might see it from a distance, or from the front as it feeds, etc. I wrote more about it in Gardening with Binoculars. Try giving it a bit more time Jory.

As a non-native, I must say that I find Crossley’s book incredible. The habitat shots depict the environment realistically and, for someone who is unfamiliar with North American habitats, this is a useful addition to bird ID. I find the far shots most beneficial as these really do capture a bird as one would see it most of the time without binoculars. How many times have we seen a bird only to raise our binoculars and its flown off, leaving the viewer with a distinctly distant impression? These, to me, are the most useful aspects of the book.

Another review from a “Mongolian viewpoint”:

http://birdsmongolia.blogspot.com/2011/03/crossley-id-guide-eastern-birds-america.html#links

Another review this time from the token 10,000 Birds Brit!

Nice, review, very useful. Great photo of how the guide “stacks up.”

A goodly number of the birds I spot and look up soon after observing them are seen from inside the cabin (or a short walk form it) up north or from a car, or within a half hour walk from the car at some reserve or park. The size of the guide is not a factor in those instances. I might get one of those cook-book holders, though, and glue it to the dashboard … 🙂

Also, I know of a number of individuals who are truly backhard birders, unable to go into the field because of physical limitations. Backyard guides and feeder guides work well in those instances, and one is often seeing the same exact birds over and over, but this sort of guide in the lap while watching the feeder and having a cup of tea works.

My review is here: http://tinyurl.com/49jgjzn

You make a very good point that this guide may be best for those between novice and expert, though some novices will benefit from the “study at home” approach, depending on the nature of one’s own visual memory.

I have one major bone to pick with this review, and it’s the sidenote at the bottom – those codes are extremely important. Those four-letter codes are used by the Bird Banding Lab to quickly designate each species, and they follow specific rules on how they created these codes that make the general rules easy to learn and make the codes easy to learn. To see you undermine the codes as having no value is highly irritating to those of us who use them regularly in our field notes and those of us who have banded. It doesn’t take much to learn them and they are very handy if your birding consists of a small notebook and pen (rather than some pre-made checklist, which I usually find fairly useless if collecting data to check into ebird).

Maybe 10000birds.com should have an article about why such codes are used and why they are important and why they were included into the guide in the first place.

@Maria: Forgive my ignorance, but it seems to me that the codes are used because they are shorter than full species names, no? Other than being shorter is there something else that makes them valuable? I did not say they have no value: I said that their only value is being shorter.

Personally, I use a 6-letter code when I am taking notes in the field because I find that it leads to less confusion, especially when I am dealing with an avifauna that I am not familiar with.

Most birders do not have any reason to learn a four-letter code and I think that many will be frustrated by their use in the text as a shorthand. Even when I report a banded bird that I spot I don’t use the 4-letter codes (they aren’t even an option when reporting them) but the common name of each species.

I got this book for Christmas. It hurts the eyes to glance at a page–I cringe at the artifacts of photoshopping with incongruent lighting and odd perspective. On the other hand, you get good value for the price in that there are lots of different views of each bird, which helps with the ID.

A year late here, but…

Re: Four letter codes. Very useful for doing point counts in those small notebooks or in the limited space provided by the cross-hair type circles on the data sheets. Most of the codes are intuitive to use, easy to learn so the charge that they’re a barrier to novices is rather a ridiculous one. Incidentally, I’ve heard the same charge levelled at the scientific names.

Every field biologist I know who does bird work uses the codes in the field, and the codes are also typed into the spreadsheets. It is a great time-saver. Then you can sort by field code so the common and Latin names can be quickly added in a frenzy of copy and paste–something which I just finished doing on a spreadsheet with 6,403 entries, and it took me less than 20 minutes. It was the inclusion of the codes that decided me on the book since I do work across a large geographical area and need to double-check on some of the less intuitive codes for species with which I am not as familiar.

Still not sure if I like the book format as a whole though. I would have liked all the different bird angles, but without the background which is too distracting. On some pages it feels like I’m playing Where’s Waldo.

@thainamu: Sounds like a good Christmas present to me!

@Daniel J Andrews: So beginning birders, when reading the description of a bird, should intuitively know what birds are being referenced as similar species because the four-letter codes are easy to learn? You, who use these codes regularly, say you like using the book to double-check the codes – and novices should have no problem learning them? Also, I somehow think that the field biologist crowd is one of the smaller subsets of purchasers of the book.

Great goods from you, man. I have bear in mind your stuff previous to and

you’re just extremely fantastic. I actually like what you’ve

obtained right here, really like what you’re saying and the best way by which you say it. You’re

making it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it sensible.

I can not wait to read much more from you. This is actually a great site.