Georg Wilhelm Steller was never in the Rockies in the first place. Also, he has been dead for more than 250 years now. Many of the species that he introduced to European science are also dead (Steller’s Sea Cow), threatened (Steller’s Sea Lion, Steller’s Eider), or have never been seen again (Steller’s Sea Ape, which modern scientists suspect was probably a young and/or deformed Northern Fur Seal.)

The Steller’s Jay, on the other hand, is doing just fine. Probably this can be chalked up to the ‘Jay’ part, not the ‘Steller’s’ part. Love them or hate them – and personally I find it hard to imagine hating them – they are all over the place.

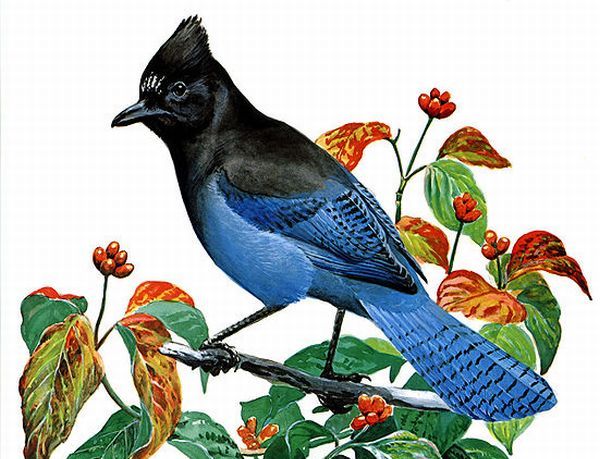

Sometimes referred to as the Long-crested Jay, Pine Jay, or Mountain Jay — and occasionally, confusingly, by area natives as the Blue Jay — the Steller’s Jay is widespread and numerous. Although its blue-and-black palette blends readily into the shadows of the conifer forest it typically calls home (and note how the vulnerable head is the least visible part) it is a striking bird once seen, and the more so when it ventures out onto a snow-covered field or road. Bright but sleek, kind of goth. I’m prepared to commit a bit of treachery and say that, to me, Steller’s Jays are even more beautiful than the actual Blue Jays back home. It’s a source of frequent wonder, to me, how coloration that looks vivid in one context can suddenly disappear in another, how perfectly beauty is adapted to utility this way (or, more likely, how well our eyes are adapted to see utility as beauty.)

One thing that seems odd, however, is that I almost always spot single Steller’s. (Sorry.) My first encounter with the species, in California, was of loud and raucous group. And corvids in general tend to be social birds – the Blue Jays at my parents’ feeders, for instance, typically show up in posses of five or six, while the winter flocking tendencies of American Crows are both famous and infamous. Moreover, Kenn Kaufman’s Lives of the North American Birds, my go-to source for bird biography, says that the species lives in flocks outside of the nesting season. On the other hand, the might and majesty of the National Park Service (in the form of the Bryce Canyon website, anyway) backs up my observations, describing it as “a solitary bird” in contrast to other jays that form large family groups.

What say you, fellow birders? Do your observations of Steller’s Jays point to them being loners or joiners? Does it vary by geographic location or habitat type?

(Image courtesy of Bob Hines, United States Fish and Wildlife Service)

Nice, Carrie! I can tell you that in the highlands of Guatemala in March, Steller’s Jays are almost oppressively social. Two years in a row, I visited Cerro Alux outside Guatemala City (here and here w/ jay photo) where raucous troops of Steller’s Jays reign supreme.

When they come to my bird feeders (here in Vancouver BC) they usually come in groups of between 2 and 6. Occasionally I see just one but even then there’s others which show up immediately after that one leaves.

It seems as though they travel as a family unit. I live in Anchorage and see the parents and babies in the summer hanging around our yard. Now, in the winter, I see that same family coming to our bird feeder. Each family has their own little territory in the neighborhood.

Solitary at our winter bird feeder, but I see pairs during the spring. And without a doubt, hearing them is unavoidable…

I agree; usually see just one.

At our feeder in Vancouver, Washington, they always came in groups of 5-10. We also had over the years two with broken wings. We are sure it was two different birds because one was a left wing and the other a right wing. Both birds returned for three years.

I think I’ve seen them in small groups, but I don’t have enough experience with them to generalize.

Steller’s are regular winter visitors to our feeder. We are at the foot of the Purcell Mountains beside Kootenay Lake in BC. They spend their summers in the mountains and return in time for the ripening hazelnuts (if the squirrels haven’t got there first.) In the spring, their raucous voices become almost lyrical as they sing and chat quietly with their mates. In this part of the world, they are seldom solitary.

I live in Puyallup, WA and have the Stellars year round – sometimes just a couple and sometimes 15 – 20. When I put the peanuts out it’s almost as if they send out a signal – Okay guys, the peanuts are out, because they come in to the feeders one right after the other. While a couple of them are in the feeders several more are sitting up on the fir tree branches waiting their turn and there are usually a couple eating corn off of the cob while waiting for their turn – and they just keep doing this and squawking the whole time – I love them!!!!!

When I lived in Denver, I always saw them by themselves, or sometimes near Magpies.

I have seen them both ways in So. Calif.’s coastal mountains at around the 7000 ft. elevation. I haven’t noticed a particular pattern, although they do gang up on the squirrels to chase them away from the peanuts put out for feeding.

Yes they love peanuts and they must be able to tell the others where the food is. When I put out the peanuts, one comes and weighs the nuts, chooses one or two, and leaves. Soon there are gobs of jays scooping up the nuts. I buy them ten pounds at a time and they never last long.

I did not know they like humming bird young however, and with 6 feeders out now and many hummers, I am rethinking the idea of this jay thing.

June 28,2011 Saratoga,CA

I too love this beautiful macho looking bird. I’ve seen them chase away hawks and get rid of the black birds that try to eat their food.

I have their feeding plate outside my kitchen window where I can see them come and eat. You know something, they eat just about anything. Mostly I feed them leftover bread. I’m trying to tame them,and it seems to be working because they are not afraid of me. Last year they made a nest right outside my kitchen window, where I have a tall slim tree or bush. It was like having them inside the house. There were two Stellars and two nests. I’m not sure how to tell the male from the female?? Anyway this year they moved the nest to the side of the house where the dinning room is. I can’t see them from the inside but it’s on the corner of where we eat. Now we have babies in the nest!!I heard them yesterday. I’m just thrilled! I’m praying the cats don’t get them.

In North Vancouver, BC my regulars are usually single or a family this time of year, same birds all year round. If I hear them squawking I just squawk back and sure enough one lands on the balcony railing, hopping up and down waiting for me to fetch a peanut! Our strata by-laws do not allow feeders so it is one peanut, shelled, broken-up one at a time.

I’ve watched the parents teach their young how to hide and find a peanut. While junior sits on the railing, ma/pa places the peanut in my planter and hops back to the railing beside junior, then retrieves it and hops back up on the railing with the peanut. This is done 8 – 10 times with the same peanut and then they both take off leaving the peanut for another time.

One jay has become so comfortable, that if the sliding balcony door is open, it will come right into the condo. It hops across the living room into the kitchen to check out if my dog has left any food in her dish. I think this one came looking for peanuts some years ago and dicovered that dry dog food is quite tasty. My dog just sits and watches from a few feet away while it gobbles up, sometimes making a few trips. It is so funny, both the bird and the look on the dogs face!

I was glad to see your post as we live on the coast, Coos Bay, and have only one Steller’s Jay busy flying to and around our several acres. I wondered because all the bird facts seem to say they live in social groups, but just one so far, but he,s firmly new maybe five months since he’s seemed to call our yard home.

I am feeling sooo sad. I’ve had my stellars coming for a few years.

Last year we had babies that were born here. This year I saw them working so hard to build their nest and they were coming and going.

Well for Memorial Day weekend we heard the babies crying out for the first time. That was Sat. Two days later I went out and found alot of the tree leaves on the side walk and I knew the cat had been there.

Sure enough the next thing I saw were the feathers. I felt so bad. Then a few days later I saw them bring some twigs and things, but this time they were going to the very top branch of the large oak tree we have next to our house. I guess they are making another nest. Do they

have more than one nest each summer? I enjoy them very much!

I’d like to find out more about them. B

I live in the San Jacinto Mtns in southern California. We have a great deal of experience with Steller’s here, having raised (and released) many chicks and rescued a number of adults. They travel in family groups of 12-13 birds. Our yard is full of fledglings of differing ages every June. The young generally stay together through winter, often forming loose groups with a few adults. I fill my feeders at varying times during the day. Until I fill them, I cannot look out any window of my house without there being at least one jay peering in at me, nor can I walk in my neighborhood without having a troop of Steller’s accompany me. Once the feeders are filled, several dozen or more jays descend upon them in a matter of seconds. I don’t recall more than a half dozen or so times that I’ve seen a solitary Steller’s in the 28 years that we’ve lived here. Western Scrub Jays (which are far less common here at 6000′), on the other hand, are invariably alone, even during breeding season.