Sometimes, it’s the simplest things that are the hardest to execute. So, while we are in awe of an identification guide that discusses every single field mark of hawks or warblers, we tend to accept without question bird identification guides that aim to teach beginning and intermediate birders how to recognize birds in their backyards, neighborhood parks, and state preserves. Which is a big mistake, because those guides are not easy to produce.

Think about it. A good state bird guide needs to offer details about a bird’s look, sound, behavior and habitat in language that is specific enough to differentiate the bird from similar-looking species, but nonscientific enough not to intimidate novice birders. And, it needs to do that in three to six sentences. And, the description needs to be accompanied by a photograph or drawing that depicts shape and important field marks. Choices need to be made, as they do with any identification guide. But, here the canvas is focused on the target geographic area and the needs of the beginning and intermediate birder. Do you include rarities, or would that confuse the birder? Do you include birds that are common migrants in one small section or the state but which are not found elsewhere? How do you organize species, knowing that beginning birders are apt to observe birds by color first and might be confused and intimidated by a taxonomic organization?

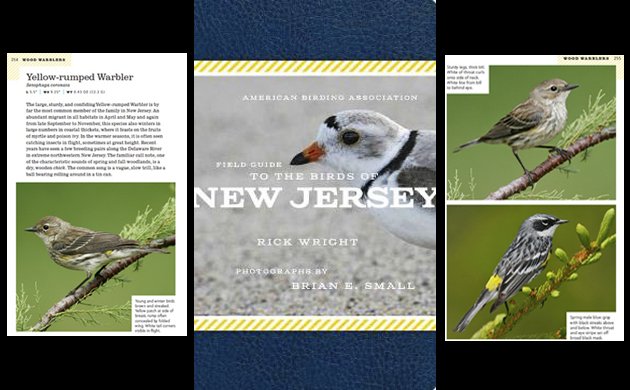

The American Birding Association (ABA) in partnership with publishers Scott & Nix have taken up the challenge of producing high-quality state bird identification guides. And, if the first book in the series, the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey by Rick Wright (author) and Brian E. Small (photographer), is representative of future titles, then they have more than met the challenge. As a birder who frequently birds New Jersey (and sometimes works and lives there), I am so happy that New Jersey is ABA state number one! (Well, in the series.) And, I am thrilled that two of the places I most love to bird–Sandy Hook and Negri-Nepote Grasslands–are amongst the areas featured. But, I get ahead of myself.

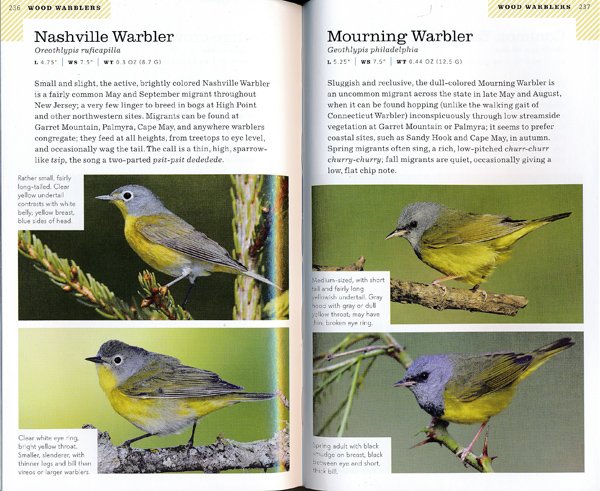

The American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey covers 255 species, birds that are abundant and common (like Nashville Warbler) in the state, plus some uncommon species (like Mourning Warbler) and scarce species (like my favorite, Grasshopper Sparrow), and several species, like Harlequin Duck, that are irregular, even rare, but notable. Species are organized in American Ornithologists’ Union taxonomic order. As I noted above, organization is a particular problem with bird books aimed at beginner birders, and there are guides that are based on color or other systems that pair look-alike species together. I expected nothing less than a taxonomic order from Rick Wright, who explains in the introduction, “It is worth learning, as it reflects the latest scientific views on the relationships and evolutional history of our birds” (p. xiv).

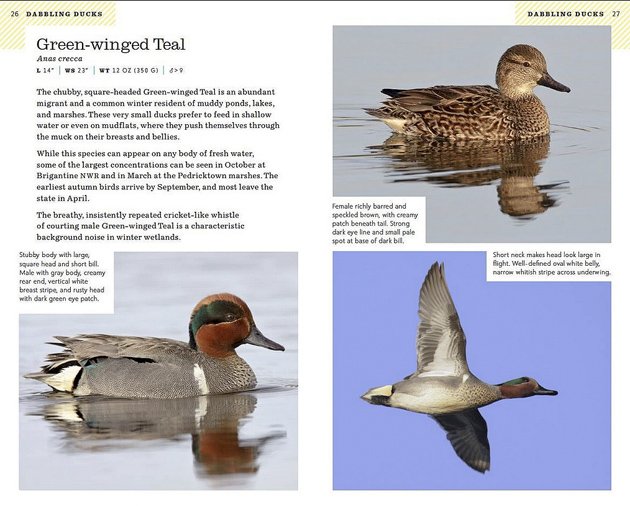

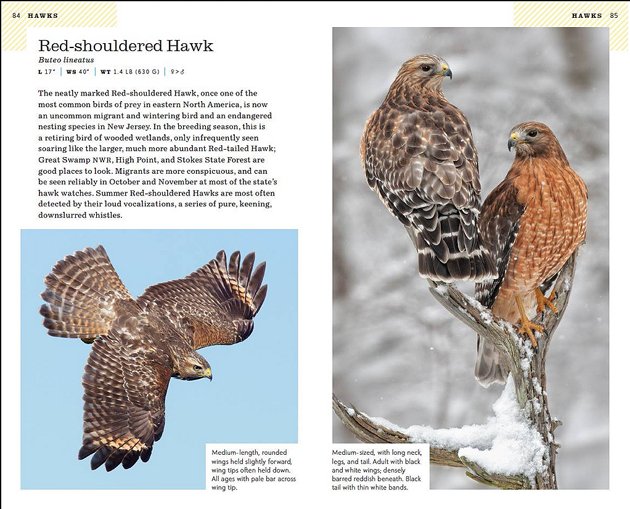

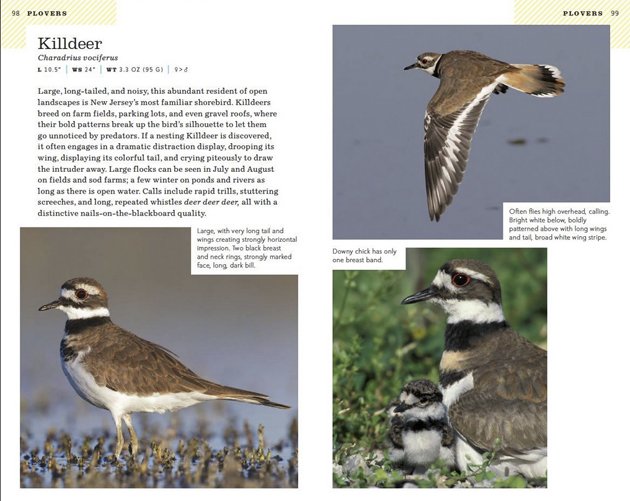

Each species account includes the following basic information: popular name, scientific name, size (length and wingspan) and weight, and symbols indicating if the male or female are larger in size where appropriate. One to three paragraphs compactly describe what the bird looks like in terms of shape and size, its habitat, and how often, where, and when the bird is likely to be seen in New Jersey. The text ends with a description or transcription of the bird’s song or call, whichever vocalization the birder is most likely to hear in New Jersey. Each species account is illustrated by one to three photographs, which are annotated with additional, more specific text on the bird’s size, shape and diagnostic field marks.

The text and photographs are excellent and, like good teaching tools, work together. Many 10,000 Birds readers know author (and New Jersey resident) Rick Wright from his activities as writer, blogger, book editor of ABA’s Birding magazine, past department editor of Birding and Winging It, WINGS tour leader, speaker, and explicator of bird history. Wright has perfected the art of describing birds in language that is specific, efficient, visual, and often fun. Green-winged Teal are “chubby” and “square-headed”; Laughing Gulls are “rakish”, “dark”, and “scimitar-winged”; Orange-crowned Warblers are “short-winged, long-tailed (and poorly named)”; Yellow-billed Cuckoos are “lanky and reptilian”. I love the way these terms paint quick, accurate portraits with a few, perfectly placed strokes. The reader can walk away with the quick image in her head, or can fill in the outlines by reading the detailed notes. (Disclosure is in order here. Rick Wright is a birding friend and also, at times, my editor in his role as Book Review editor for Birding. He is a professional who would definitely not approve of any review that was not critically honest.)

The photographs are an ordered procession of colorful, sharp images showing the full body of each species in clear light with uncluttered backgrounds. Brian E. Small, the guide’s main photographer, has contributed to many birding field guides and articles; he was photo editor of Birding magazine for 15 years and comes from ABA royalty—his father, Dr. Arnold Small, was one of the organization’s founders. About 17 additional photographers are credited in the back of the book, with Mike Danzenbaker being the most prolific contributor after Brian. Many of the photos offer hints of habitat and behavior—a Short-billed Dowitcher takes a step in shallow water, two Red-shouldered Hawks perch back-to-front on a snow-covered snag, a White-throated Sparrow sings to the heavens, his mouth agape. In most cases, the photo is so sharp you can see individual feathers.

The brief Introduction explains basic concepts like scientific names and taxonomy, and illustrates bird anatomy in six pages of labeled photographs. Most field guides show photos or diagrams of birds with arrows pointing to the eye line, primaries, secondaries, etc. Wright and Small offer additional material, illustrating anatomical parts, like wing stripe, tail band, and rump, that are used in the species accounts. I think beginning birders will find this section very useful; often, diagrams are not enough.

The Introduction is where you see that this really is a book about New Jersey. The section on “Bird Habitats” isn’t just a general description of various places where you are likely to find birds, it lists the specific types of habitats found in New Jersey and which species you are most likely to find there. “Birding Sites in New Jersey” lists the state’s major birding sites, their counties, the best season to bird the sites and what types of birds will be found at each. “A Year Afield” recommends two Jersey sites to bird for each month of the year.

New Jersey is a state that non-native birders usually think of in two words–Cape May. It is a sign of Wright’s thoroughness that recommended birding sites span the state, from the Skylands of Sussex County in the north to the small grassland preserves of central Somerset County to the marshes of western Salem county to the jetties and beaches of the Atlantic coast in Monmouth, Ocean, and Cape May counties. Major hotspots like Garret Mountain Reserve, Scherman Hoffman Sanctuary, Sandy Hook NWR, and, yes, Cape May, are cited, but also smaller, less-known birding spots like Rogers Refuge, Walker Avenue Wetlands, and my Negri-Nepote. A map of the state on the inside front cover shows where most of these sites are located. (There are some inconsistencies with this map that I hope will be corrected in future editions.)

Wright pointedly recommends William Boyle’s Guide to Bird Finding in New Jersey for more on where to bird in the state. He also lists resources for the birder who wants to know more about New Jersey birds and study a more complete bird identification guide. I can’t tell you how unusual this is. Too many bird field and identification guides don’t offer readers paths to “Additional Resources”, which really bothers my librarian mind. The book ends with the “Checklist of the Birds of New Jersey” as of 2013, a Species Index (by popular and scientific name), and, on the very last page, a Quick Index. An additional aid to finding specific birds is the page design, which places page number and bird group on the upper left and right hand corners of the left and right pages. The black print on a diagonally-striped goldenrod-and-white background makes it easy to browse though the book.

The book itself is field-guide sized, small enough to fit into a large pocket, light enough to carry in a backpack without tipping you over. A rarity these days! The binding appears to be strong enough to survive bending back and travel. The black flexi-cover with the paper slip-on title page (featuring a Piping Plover, the treasured endangered shorebird of the east coast) harks back to the Audubon Field Guide series (actually still in print). When I take the slip-on cover off, the book–plain black with small white lettering–looks old-fashioned to my eyes. My daughter tells me it’s vintage enough to be hip. I’m getting used to it, and I’m willing to accept this type of binding if it means reasonable pricing for the series.

I was a bit surprised when I learned that the American Birding Association was initiating a State Field Series; it seemed like an expensive and challenging initiative. But, now that I’ve read American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey, I want to applaud the idea and the product. This is the perfect field guide for beginning and intermediate birders who live or work in New Jersey, and is likely to be of interest to newbie and even experienced birders who live in New York State and Pennsylvania. In fact, any birder planning to bird New Jersey will benefit from using this book. Its only decent competition is the National Geographic Field Guide to Birds: New Jersey (2005); a good guide, but one that contains far fewer species accounts (about half of the ABA book’s coverage) and outdated taxonomic information.

Add to coverage and currency Rick Wright’s lively, factual text, his intimate knowledge of New Jersey birds and birding, and Brian Small’s excellent photographs, and you have a field guide that will enhance the birding experiences of intermediate birders and help new birders become a part of our tribe. I am looking forward to reading the next book in the series, American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Colorado, by Ted Floyd and Brian E. Small, due out in June 2014. And, I am very much looking forward to birding places in New Jersey beyond Negri-Nepote and Sandy Hook, with the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey, that hip-looking state field guide, in my backpack.

———————–

The American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of New Jersey

(American Birding Association State Field Series)

by Rick Wright (Author) and Brian E. Small (Photographer)

Scott & Nix, Inc., April 2014.

368p.; product dimensions: 4.60 (w) x 7.30 (h) x 1.00 (d)

ISBN-13: 9781935622420

$24.95 retail (note: If ordered from Buteo Books a portion of your purchase goes towards supporting the ABA and its programs)

Leave a Comment