There were three profound questions my birding group discussed while we birded Trinidad and Tobago, back in December 2012:

(1) How many Bananaquits could fit on a banana?

(2) Which hummingbird was more beautiful—Tufted Coquette or Ruby-topaz Hummingbird?

(3) What was the best guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago?

The first two questions were never definitely answered. Experiments in the field (the famed Asa Wright Nature Center veranda) involving Bananaquits and bananas came up with numbers ranging from 7 to 16, but a tanager always came along to interfere with Bananaquits’ noisy appreciation of their namesake fruit. And, as far as the hummingbirds were concerned, when it came down to it we really didn’t care, we just wanted more photo ops for both.

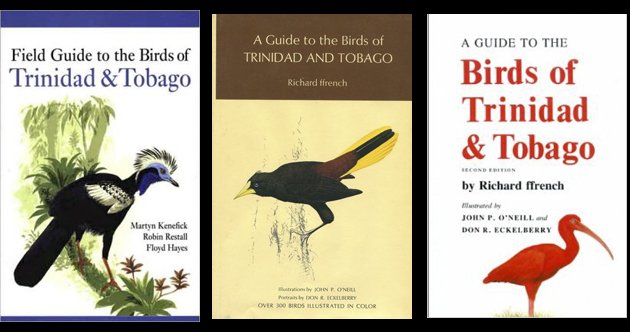

The bird guide question was a conundrum. My friend Ian had purchased Richard ffrench’s classic A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago just before we left, the third edition, hot off the presses. I had purchased the Field Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago by Martin Kenefick, Robin Restall and Floyd Hayes on Amazon. It was lighter than the ffrench guide, and the blue-bordered cover depicted Trinidad’s signature bird, the seldom-seen Trinidad Piping-Guan. Steve, another member of our birding group, also had a field guide by Kenefick, Restall, and Hayes, but his was bordered in GREEN, had a slightly different title, and, to my extreme chagrin, was much more recent, showing the recently split Trinidad Motmot instead of the Blue-crowned Motmot on my book’s cover.

I was confused. How could this happen? How could I, the librarian, end up with an outdated field guide? And, to make things even more confusing, why did Ian’s 2012 ffrench guide list the motmot under its old name, Blue-crowned Motmot?

A little bit of research when I got home unraveled the ways of publishers here and in Great Britain. There are two editions of the Kenefick book, the field guide. The first, Field Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago, was published by Christopher Helm in London in 2007 and then published in the United States in 2008 by Yale University Press. The second edition, with the slightly different title Birds of Trinidad & Tobago, was published in London in 2011. For some reason, Yale University Press discontinued its arrangement with Helms, so there is no United States edition. This is why the most recent title did not show up on Amazon when I was book shopping (it is there now, a year later, but only for purchase through third-party booksellers). The 2011 edition of the Kenefick book, the one with the green-bordered cover, can also be purchased through Buteo Books, the Book Depository and a couple of other online booksellers. I wish I had figured this out before I headed to Trinidad and Tobago with an out-of-date field guide!

Do not buy these books, unless you are collecting old bird books.

The question still remains, especially for travelers with little room in their luggage: Which guide should I use when birding Trinidad and Tobago?

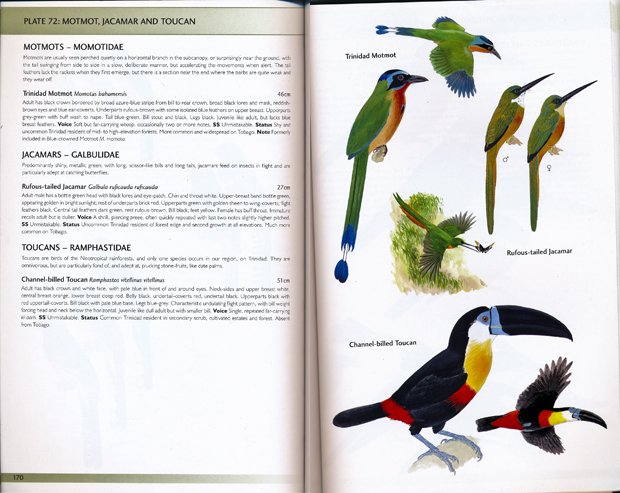

Richard ffrench’s A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago is the classic bird guide for the islands. First published in 1973 in association with the Asa Wright Center, the book focuses on species descriptions, with illustrations grouped together in plates positioned in the center of the book. It is organized taxonomically, with families identified by first scientific and then popular name. Each family section starts with a brief description of the birds within that family, their common physical and behavioral traits, and range of habitat. Families are ordered according to the 7th edition of the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) Checklist of North and Middle American Birds, which explains why the Trinidad Motmot split is not included. The AOU has not accepted that split. The guide covers 477 species, an expansion of 35 from the second edition, which was published in 1991.

Each species account consists of: Popular name, scientific name, alternate names (six for the Trinidad Piping-Guan!), plate number, and sections on Habitat and status, Range (descriptive, no maps), Description, Measurements, Voice, Food, Nesting, and (usually) behavior. The amount of information varies, with less material on vagrants and rare species, and extended entries on notable species. The accounts aim for specificity and authority; dates and locations of rarity sightings are given, and research articles on nesting and behavior are cited. Accounts are most complete for notable Trinidad species, such as Scarlet Ibis, Trinidad Piping-Guan, White-bearded, Blue-backed, and Golden-headed Manakin. The manakins’ famous display behavior is described in such great detail, you can actually see them jumping, sliding, flicking their wings and synchronously calling in your mind.

ffrench’s descriptions are delightfully uneven, reflecting his personal experiences with the birds, his research, and his personality. He does not seem to be as entranced by Trinidad’s hummingbirds as my friends and I were, noting the aggressiveness of the Ruby-topaz Hummingbird with scientific detachment. But, he apparently really enjoyed Laughing Gulls, writing, “I have found these gull extremely gregarious, particularly in the evenings….Most unusual of all, in Tobago I watched a flock of about 20 gulls feeding on the berries of a manjack tree 100 m above sea level and well over a kilometer from the shore. The birds took the fruit on the wing, hovering beside the branches in a rather ungainly fashion.” And, while he writes full accounts of all five species of Furnariidae (Ovenbirds), the Yellow-chinned Spinetail is clearly his favorite: “An extremely noisy and conspicuous species. Even during the breeding season the birds appear to be quite unwary of humans. Often, as I have been investigating the contents of a nest by making a small hole in the side, the parent birds have come right to the nest, where they immediately begin to repair the damage even before my departure!”

The bird illustrations in the third edition are brand new, updated by a group of eight artists working under the direction of John P. O’Neill, the original illustrator and funded by the Asa Wright Nature Center. (O’Neill illustrated the identification plates in the first edition and Don R. Eckelberry, cofounder of the Asa Wright Nature Center and noted wildlife artist, did portraits of local birds.) Principal artists are O’Neill, John Anderton, Dale Dyer, and John Schmitt. Artists utilized museum specimens obtained from a number of museums to ensure accuracy.

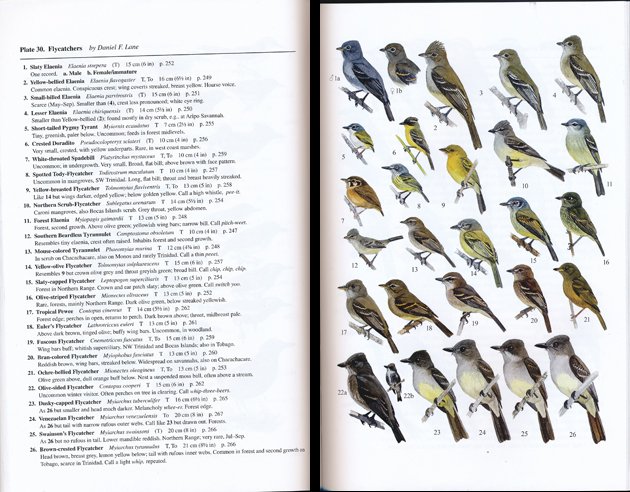

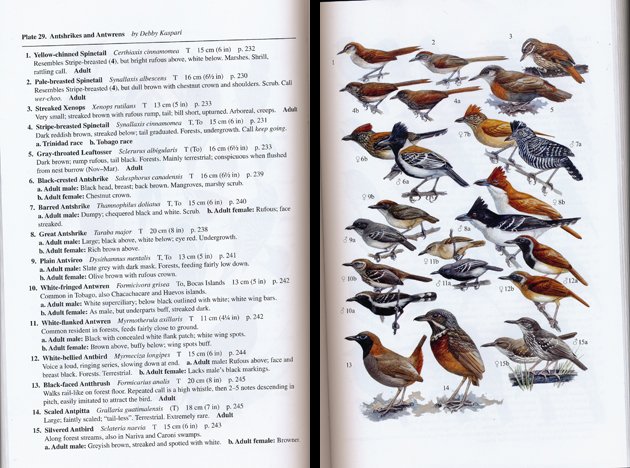

And, they are beautiful. Forty plates illustrating 477 species means that each plate contains 5 to 18 species, often with illustrations of more than one form of the species (adult, immature, male, female, flight, breeding, nonbreeding, nonbreeding adult in flight, you know the permutations). Colors are subtle and bright, distinctive details are evident, and birds on each plate are sized comparatively. Care has been taken to group the birds within each plate in a way that embraces design while also emphasizing similarities and differences. For me, this is most striking in Plate 30, Flycatchers, where the eye is arrested by the image of Elaenia after Tody-Flycatcher, after Scrub-Flycatcher after Tyrannulet after Pewee after Flycatcher, all looking left, all alike you think, till you start noticing that some are smaller, some have yellowish breasts, some have larger crests or larger bills.

Each artist is credited on the top of the text plate page. Despite the unusually large number of illustrators, the images are painted in a uniform enough manner that you aren’t distracted by individualities in style. Still, there is enough of a difference that I knew Warblers were painted by a different artist than the one who painted Cuckoos (O’Neill did the Warblers, Anderton the Cuckoos). Each plate is coupled with a companion page listing birds depicted, popular and scientific names, plus size, page number of Species Account, and notes on important identification details.

In addition to the Species Accounts, ffrench has written a 32-page Introduction on the History of Ornithology in Trinidad and Tobago and The Environment of Trinidad and Tobago. Habitat areas are described in terms of climate and vegetation and how that has changed and what that means for birds. This section is illustrated by 13 black-and-white photographs, and if there is one way in which I would want edition four to be improved, it would be to print better quality photographs or go to color, since the images in my volume are dark and not very helpful in understanding the text.

The back of the book material consists of the “Species Checklist for Trinidad and Tobago, with Locations of Collected Specimens,” a Bibliography, and two indexes, one of Scientific Names and one of Common Names. The Bibliography is extensive (14 pages) and scholarly. No online sources are cited, but if you want to know what articles ffrench or Alexander Skutch or Barbara and David Snow wrote on West Indian birds, this is the place. The Indexes are purely by name. This means that you need to know that it is Trinidad PIPING-Guan, not Trinidad Guan, and that hummingbird species include hermits, emeralds, sapphires, mangos, a goldenthroat, a jacobin, a sabrewing, and a coquette, because you will only find the two hummingbirds that have the word ‘hummingbird’ in their name under the term Hummingbird.

Richard ffrench is known in the birding world as the expert on the birds of Trinidad for good reason. Born in Great Britain, he originally travelled to Trinidad in 1958 to teach music and history, and quickly became enamored with the Neotropical birds of the West Indies. His introduction to research started with his friendship with David and Barbara Snow, Americans who were engaged in groundbreaking research on some of Trinidad’s most notable species–Bellbirds, Oilbirds, and Manakins. ffrench started banding birds in 1959 and was soon doing research, with his wife Margaret’s help, on Scarlet Ibis, migrant shore birds, terns, and Dickcissels. He helped establish the Asa Wright Nature Center, wrote many articles promoting the importance of wildlife conservation in Trinidad, mentored birders and ornithologists interested in the islands, and, once he and his family returned to Great Britain in 1985, returned regularly to lead bird tours and continue research for his guide.*

Richard ffrench died in 2010 at the age of 80. He was in the middle of rewriting and updating this third edition when he died. The “Editor’s Note” by R. Geoff Gibbs and “Artist Acknowledgements” by O’Neill give us a sense of how much work he had already done and how much more needed to be done to complete the book. Gibbs writes that ffrench asked him in 2009 to “prepare the short texts to accompany the plates of species not illustrated in earlier editions, and that his family asked him later on to work with the publisher to complete the book. O’Neill makes a point that “Richard kept the text for a new edition of the book regularly updated.” Graham White, a member of the Trinidad and Tobago Rare Bird Committee, reviewed the final text; Gibbs states that his comments were received in January 2011. Clearly, ffrench’s colleagues and family made sure that this edition maintained the standard of excellence that the earlier editions that characterized the earlier editions. An article on the Asa Wright Nature Center website, The Return of Richard ffrench, http://asawright.org/2013/02/the-return-of-richard-ffrench/, gives a sense of how much the people of Trinidad value his work, and how much the ffrench family loved Trinidad.

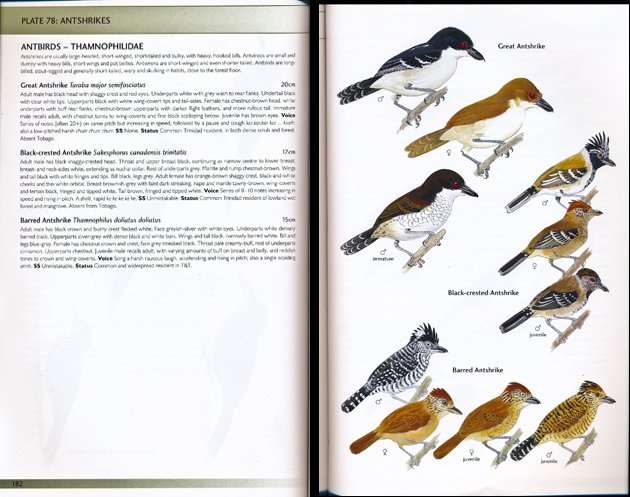

Birds of Trinidad & Tobago, second edition by Martin Kenefick, Robin Restall, and Floyd Hayes has a simple goal, “to provide a portable tool equipping birders and ornithologists alike with the information required to accurately identify birds in the field.” It is organized in typical modern field guide style, with illustrated plates opposite brief species accounts. At 272 pages, it is briefer, lighter, and a tad bit smaller in height and width than ffrench’s guide. Illustrations are from Restall’s Birds of Northern South America: An Identification Guide, and, according to the book’s publicity material, many have been “re-worked” and repainted for the new edition.

Species accounts are comprised of: popular name, scientific name, size, physical description (male, female, immature, juvenile when appropriate; nonbreeding plumage for shorebirds, terns, gulls), voice, similar species, and status. No nesting or behavior or natural history, just the essentials needed for identification. The status section differentiates between the bird’s status in Trinidad and Tobago, occasionally citing records of accidentals. The accounts are organized according to the AOU’s South American Checklist, which does accept the motmot split.

There are 115 plates, 35 more than the ffrench guide, and 18 more than the first edition. With fewer species per plate, we often get more images of various forms of a species. There are four images of Roseate Tern in ffrench, for example, and six images in Kenefick; two images of Barred Antshrike, adult male and female, in ffrench, and four images, adult male and female, juvenile male and female, in Kenefick (images of Barred Antshrike plates are above). Images are beautiful here also, but the color and depth appears flatter than the ffrench artwork. I’m not sure if this is a function of the “reworking” of the original artwork or the printing. The artwork in my edition of Birds of Northern South America is much more intense in color. And, with the absence of the need to arrange multiple images on one plate, there is less a sense of artistic design, birds are arranged in simple but unimaginative rows.

The team that put this field guide together is knowledgeable and distinguished. Martyn Kenefick is a British-born ornithologist and bird guide who has lived in Trinidad since 1999; he has been secretary of the Trinidad and Tobago Rare Birds Committee since 2001, overlapping with ffrench’s tenure on the committee. Robin Restall is principal author of the two-volume Birds of Northern South America and was executive director of the Phelps Ornithological Collection, Caracas, Venezuela. He is now a director of the Phelps Foundation. Floyd Hayes is professor of biology at Pacific Union College and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology.

Like any decent field guide, the book’s introductory material includes material on how to identify a bird–diagrams showing the names of bird parts (also from Birds of Northern South America), a glossary, and factors that influence how a bird looks. There is a very brief description of Trinidad and Tobago’s habitats and climate, an explanation of taxonomy, and a nice 7-page section of “Where to Watch Birds on Trinidad and Tobago.” There appears to have been little change in this text from the first edition.

Back of the book material consists of the “Official Checklist of the Birds of Trinidad & Tobago” (in a more usable format than ffrench’s list), The Trinidad & Tobago Rare Bird Committee Review List, and an Index of common and scientific names. Again, you gotta know your hummingbird names to use it.

There are two things that bother me about the Kenefick guide. The first is that the illustrations make no distinction between birds common in Trinidad and Tobago and rarities or escapees. Flipping through the book and spotting the large and unusually bright images of macaws on Plate 58, you’re apt to think like I did that these large, beautiful birds are easily found on the islands. Nope. Red-and-green Macaw is an “escaped small feral population,” Scarlet Macaw has been sighted two times in Trinidad, the most recent sighting in 1943, and Blue-and-yellow Macaw was locally extirpated in 1970, with a re-introduction program in place. I’m sorry, but this is just deceptive! French has no species account for Red-and-green Macaw, a brief species account but no image for Scarlet Macaw, and a species account with a small image on the related plate for Blue-and-yellow Macaw.

There are two things that bother me about the Kenefick guide. The first is that the illustrations make no distinction between birds common in Trinidad and Tobago and rarities or escapees. Flipping through the book and spotting the large and unusually bright images of macaws on Plate 58, you’re apt to think like I did that these large, beautiful birds are easily found on the islands. Nope. Red-and-green Macaw is an “escaped small feral population,” Scarlet Macaw has been sighted two times in Trinidad, the most recent sighting in 1943, and Blue-and-yellow Macaw was locally extirpated in 1970, with a re-introduction program in place. I’m sorry, but this is just deceptive! French has no species account for Red-and-green Macaw, a brief species account but no image for Scarlet Macaw, and a species account with a small image on the related plate for Blue-and-yellow Macaw.

My other problem with Kenefick is the font, which is teeny tiny and thin in the second edition. I could barely read it, and if you buy this book and you are over 50, I highly recommend you also buy a magnifying glass. Ironically, the font in my first edition is much better, and I ended up happy I had bought this edition for my trip after trying to read the skinny-font second edition.

Putting these points aside, this is a very good field guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago. I like the fact that it is dedicated to Richard ffrench, “the father of ornithology in Trinidad & Tobago,” and the comment that his reaction to the first edition was “characteristically kind ad generous and most encouraging.”

So, back to that burning question, which is the best guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago? The answer has to be Richard ffrench’s A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad and Tobago, 3rd edition, which is authoritative, comprehensive and has beautiful artwork. Using the ffrench guide while you’re in Trinidad and Tobago allows you to learn on-site, as you are experiencing the birds. The downside to the ffrench guide is that you have to flip back and forth between the plates and the species accounts. And, it’s really big and heavy!

Before the publication of the Kenefick guide, birders visiting Trinidad and Tobago would often extract the plates and bind them separately. It’s nice that this is no longer necessary. The Kenefick title offers a compact, concise up-to-date field guide to these wonderful birds, the ibis, the piping-guan, the chachalaca, the manakins, and the many species of terns, flycatchers, hummingbirds, raptors, antbirds, woodcreepers, and tanagers. If you can read the font and remember that not every bird depicted can actually be seen in the country, then this might be the preferable purchase. Of course, you then miss out on all the natural history, the nesting data, descriptions of eggs, mating rituals, and ffrench’s personal, affectionate observations of his birds.

This is the hard decision, made all the harder because both books are pricey, and Amazon discounts cannot always be obtained. I can’t make it for you, but I am interested in knowing what your choice would be or has been in the past. One thing to keep in mind is how fortunate we are to have this choice! Trinidad and Tobago is one of the few Caribbean countries where a birder has a choice between two guides less than three-years old. It is far easier to find out how to identify a juvenile Bananaquit than it is to research how many Bananaquits fit on a banana. But, maybe that is the way it should be.

[Both Mike and Corey have visited Trinidad and Tobago. If you want to read more about the birds of the islands and less about the books about the birds, I suggest Mike’s exciting post about Getting the Guan (Pawi Edition) and Corey’s post about The Caroni Swamp Scarlet Ibis Show. I don’t know which bird guides they used on these trips.]

*Biographical information about Richard ffrench is from “Richard ffrench Obituary,” by Geoff Gibbs, The Guardian, June 2, 2010.

————————-

A Guide to the Birds of Trinidad and Tobago, 3rd edition.

By Richard ffrench, Illustrated by John P. O’Neill, John Anderton, Dale Dyer, JohnSchmitt, Foreword by Carol J. James.

Comstock Publishing Associates, imprint of Cornell University Press, December 2012.

Paperback, 524 pages, 108 illustrations including 84 color plates, $39.95 (list price).

ISBN-100-8014-7364-0, ISBN-13978-0-8014-7364-7

Birds of Trinidad and Tobago, 2nd edition (Helm Field Guides).

by Martyn Kenefick, Robin L. Restall, Floyd Hayes.

London: Christopher Helm, imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011.

Paperback, 272 pages, 107 color plates; $39.95 (list price).

ISBN-13: 9781408152096

ebook version available for iPad, see publisher’s page.

ISBN 9781408181218

Hello Donna

I just read your very interesting review of these books. I am someone who is interested in nature generally. I am pleased to inform you that some 8 years onwards to your review, the macaws are indeed alive and well throughout the southern part of Trinidad. I have observed them in La Brea, South Oropouche, Siparia and Morne Diablo, and know that they are also in the Nariva Swamp.

They nest in holes of old Palmiste palm trees. They can be seen daily among certain populated areas flying and swacking as they leave their homes on mornings and return on evenings. The blue and yellow macaw are the more popular, but there are also communities of scarlet macaws. I was disappointed when I could not find out much about them in

ffrench’s book, but now realise why this was so.