I spent the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in the usual post-hurricane activities—looking for storm birds, making sure my loved ones were o.k., trying to grasp the enormity of what had just happened, and reading this book, The Feathery Tribe: Robert Ridgway and the Modern Study of Birds by Daniel Lewis. My daughter thought it was an odd choice—nonfiction, on the scholarly side. I found it oddly comforting because as a history of ornithology, of birding making the leap from passionate hobby to passionate profession, The Feathery Tribe shows us that we can impose some kind of order on the chaos that is nature, even if that order is always changing.

I spent the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in the usual post-hurricane activities—looking for storm birds, making sure my loved ones were o.k., trying to grasp the enormity of what had just happened, and reading this book, The Feathery Tribe: Robert Ridgway and the Modern Study of Birds by Daniel Lewis. My daughter thought it was an odd choice—nonfiction, on the scholarly side. I found it oddly comforting because as a history of ornithology, of birding making the leap from passionate hobby to passionate profession, The Feathery Tribe shows us that we can impose some kind of order on the chaos that is nature, even if that order is always changing.

The Feathery Tribe is both a biography of Robert Ridgway, the Smithsonian Institute’s first curator of birds, and a study of the historical and intellectual events which gave birth and form to ornithology. Ridgway, born in 1850 in Mr. Carmel, Illinois, was a boy many of us would recognize; all he wanted to do was bird. And, draw birds. And, identify the birds he saw and drew. This led to a correspondence with Spencer Fullerton Baird, then assistant secretary of the Smithsonian, the mentor of many naturalist/scientists of Ridgway’s generation, himself a disciple of John James Audubon, and, yes, the Baird of Baird’s Sparrow. (Reading this book is, in addition to everything else, an exercise in getting to know the originals of many of our apostrophized birds. Baird, Brewer, Cory, Bicknell, and Worthen all make appearances. Ridgway himself had 23 species, 10 subspecies, and two genera of birds named for him, including Ridgway’s Hawk.) By the age of 16, thanks to Baird, Ridgway was part of the team of the Fortieth Parallel Survey, one of the great surveys of the western frontier. The team explored Nevada and Utah, with Ridgway collecting thousands of bird specimen, plus nests and eggs for the Smithsonian. It was the adventure of a lifetime, made even more exciting by a travel route that went through Panama and Mexico, where Ridgway was exposed to Neotropical birds, a passion that informed his later work.

Ridgway spent the rest of his career in the Castle, the Smithsonian building that then housed the National Museum’s bird collection. That’s a photo of Ridgway’s office on the right, fifth floor of the South Tower. There were collecting trips to Florida, Costa Rica, and his home state of Illinois, a trip to Alaska in 1899 as part of the famous Harriman Alaska Expedition, but the work that is chronicled and celebrated in this book is largely intellectual: co-founding the American Ornithological Union (AOU), supervising the creation of the great bird skin collection at the Smithsonian, writing one of the first comprehensive North American checklists, co-writing the first AOU checklist, engaging in passionate arguments about the form bird names should take, and describing hundreds of new bird species. (When the term “describing new species” is used here, it doesn’t mean simply sitting down and writing a paragraph about a bird, it means describing the “type specimen” anatomically and scientifically, creating the authoritative description of the species or subspecies that all future sightings of the bird would be measured against.)

Ridgway spent the rest of his career in the Castle, the Smithsonian building that then housed the National Museum’s bird collection. That’s a photo of Ridgway’s office on the right, fifth floor of the South Tower. There were collecting trips to Florida, Costa Rica, and his home state of Illinois, a trip to Alaska in 1899 as part of the famous Harriman Alaska Expedition, but the work that is chronicled and celebrated in this book is largely intellectual: co-founding the American Ornithological Union (AOU), supervising the creation of the great bird skin collection at the Smithsonian, writing one of the first comprehensive North American checklists, co-writing the first AOU checklist, engaging in passionate arguments about the form bird names should take, and describing hundreds of new bird species. (When the term “describing new species” is used here, it doesn’t mean simply sitting down and writing a paragraph about a bird, it means describing the “type specimen” anatomically and scientifically, creating the authoritative description of the species or subspecies that all future sightings of the bird would be measured against.)

Robert Ridgway wrote over 500 articles and 23 books, illustrating many of them himself. He wrote about birds in North America, Central America, and parts of South America, including the Galapagos. As the Smithsonian’s bird curator, he was the first and last information point for thousands of questions about birds from bird watchers and students; he basically did for them what the Internet does for us now. He advised the first bird clubs, including one named after him, and mentored gentlemen new to the field. (The new profession of ornithology was not welcoming to women, who were associated with a less rigorous way of looking and writing about birds.) He authored two major works: the multi-volume The Birds of North and Middle America, also known as United States National Museum Bulletin 50, and Color Standards and Color Nomenclature, a work that gave rise to the term “Ridgway colors”.

It also soon becomes clear that Ridgway was prodigiously hardworking, devoted to birds, sometimes devoted to his wife and child, but not a very lively person. This is probably one of the reasons Daniel Lewis,the author,turned from writing a popular biography to a history of ornithology as a science and the ornithologist as a profession. After two chapters devoted to Ridgway’s youth and Smithsonian years, Lewis turns to the larger picture: the birth of the AOU, the growth of bird study collections, the struggle to compile a standard checklist and a code of nomenclature (rules for naming birds). Opening up the ornithological stage like this gives us a window into the careers and personalities of Ridgway’s contemporaries, including the dynamic Elliott Coues, who today might be called Ridgway’s “frenemy”. Coues spearheaded the creation of the AOU, wrote the North American birds checklist that competed with Ridgway’s, and seemingly never missed an opportunity to proclaim himself the premier bird expert of the United States, often denigrating Ridgway and their colleagues at the same time. Lewis quotes from Coues’ letters, and they are a gossipy delight, questioning Ridgway’s qualifications to be an associate editor of the new AOU journal, The Auk; devising an AOU tiered membership system that relegated “narrow-minded and intolerant” amateurs to corresponding status, and flailing against Ridgway’s criticism of his work. Other personalities who liven this tale include Joel Allen, AOU’s first president and the future first head of the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Ornithology , and Henry W. Henshaw, a personal friend as well as colleague who spent years studying the birds of Hawaii and who was known even then for his enthusiastic shooting and collecting practices.

It also soon becomes clear that Ridgway was prodigiously hardworking, devoted to birds, sometimes devoted to his wife and child, but not a very lively person. This is probably one of the reasons Daniel Lewis,the author,turned from writing a popular biography to a history of ornithology as a science and the ornithologist as a profession. After two chapters devoted to Ridgway’s youth and Smithsonian years, Lewis turns to the larger picture: the birth of the AOU, the growth of bird study collections, the struggle to compile a standard checklist and a code of nomenclature (rules for naming birds). Opening up the ornithological stage like this gives us a window into the careers and personalities of Ridgway’s contemporaries, including the dynamic Elliott Coues, who today might be called Ridgway’s “frenemy”. Coues spearheaded the creation of the AOU, wrote the North American birds checklist that competed with Ridgway’s, and seemingly never missed an opportunity to proclaim himself the premier bird expert of the United States, often denigrating Ridgway and their colleagues at the same time. Lewis quotes from Coues’ letters, and they are a gossipy delight, questioning Ridgway’s qualifications to be an associate editor of the new AOU journal, The Auk; devising an AOU tiered membership system that relegated “narrow-minded and intolerant” amateurs to corresponding status, and flailing against Ridgway’s criticism of his work. Other personalities who liven this tale include Joel Allen, AOU’s first president and the future first head of the American Museum of Natural History’s Department of Ornithology , and Henry W. Henshaw, a personal friend as well as colleague who spent years studying the birds of Hawaii and who was known even then for his enthusiastic shooting and collecting practices.

The bulk of this book, however, focuses on the ornithological practices of the time and how they supported the development of ornithological classification and naming systems rooted in Darwinian evolution. It’s challenging reading. Lewis is Dibner Senior Curator of the History of Science and Technology and Chief Curator of Manuscripts at The Huntington Library in California. He adheres to high levels of scholarship, basing his text on a wealth of primary materials, including reams of letters by Ridgway and his colleagues. There are many quotations and many details; descriptions of fights over whether species should be classified according to the structure of bones or type and placement of feathers, over whether scientific names should be capitalized or in small caps, and over the great trinomial question, whether scientific names should consist of two or three parts.

There were times when I felt like I was being buried by details, at which point I was usually saved by an anecdote about Coues, an unexpected quotation by Ridgway (I particularly enjoyed his comments on the perplexity of classifying Empidomax flycatchers), or a reminder of the importance of classification and taxonomy. As a librarian, I can relate to that, even though I managed to obtain a library degree without taking a cataloging class.

When Lewis trusts his instincts and looks at the stories that emerge from the letters of the feathery tribe he comes up with interesting conclusions. For example, he notes that despite their youth and nonstop activity, these men and even their colleagues in other countries articulated periods of “nervous prostration”, “lethargic” mind, and physical breakdown to the point where they could not work for long periods of time. Putting together the pieces, Lewis points out that only arsenic poisoning, used by all of them to prepare skins, could account for such symptoms. It is an aha! moment, one that makes you think how lucky we are that we don’t need to shoot and skin birds and how ironic it was that these pioneers of ornithology were being poisoned by their passion. I think Lewis could have given us more of these insights if every once in a while he had allowed his imagination to take precedence over the scholarly process.

The last two chapters focus on Ridgway’s publications: his books about birds and his books about colors. I found the material about the color books fascinating. Color is something that you take for granted until you realize that the photograph you worked so hard to process via Photoshop is showing up twenty degrees paler on your work computer than on your home laptop. Color is mutable and changeable and one person’s plain old red is another person’s Begonia Rose. Ridgway was obsessively devoted to producing his best known work, Color Standards and Color Nomenclature. He wanted to create color standards to describe birds. He ended up producing THE standard reference for anyone who was involved in a profession or passion that involved color. He created and named 1115 colors, devised a way to create color swatches that did not discolor or fade, and self-published the book with funding from Costa Rican naturalist José Zeledón. Each book had to be assembled individually, with his wife Evvie cutting the color swatches herself; the project not very profitable. Color Standards and Color Nomenclature is available online through Google Books, and if you have any interest in color, it is worth looking at, if for not other reason than to see the names Ridgway invented. The scientist who spent most of his life writing books about birds that focused on their measurements and physical realities here indulges in whimsy with his Lemon Chrome, Dragon’s Blood Red and Burnt Lake. You can get a taste of what the color book colors look like here, a screen shot of a section of one of the color plates digitized by Google Books.

The Feathery Tribe ends with an Epilogue on Ridgway’s death and legacy, an Appendix listing his published works, extensive Notes, Bibliography and Index. The bibliography is impeccable, as befits a publication of Yale University Press, but I would like to make a pitch here, again, for the inclusion of links to free online versions of articles when they are available. Early issues of The Auk and The Condor, the ornithological bulletin of the Cooper Ornithological Club, are available free online through SORA (Searchable Ornithological Research Archive) and copies of Ornithologist and Oologist are available free through Google Books. Let’s share the digital wealth and make it easy for people to read the early literature of our tribe!

The Feathery Tribe is a scholarly history of how ornithology became a science, told through the prism of the life and career of Robert Ridgway. Previous histories of birding, the excellent Of A Feather by Scott Weidensaul (Harcourt, 2007), A Passion for Birds by Mark Barrow (Princeton Univ. Press, 2000), and A World of Watchers by Joseph Kastner (1987) focused on birding and its personalities. The Feathery Tribe focuses on ornithology and its ideas and its professional infrastructure. It is not a book for everyone. It is challenging, at times dense, but also enlightening and informative, particularly for those of us who read every new supplement of the AOU Checklist of North American Birds. http://www.aou.org/checklist/north/ . The next time you hear birders complain about lumping, tell them to be thankful they weren’t around in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when hundreds of supposedly new species were re-assigned subspecies. status And, the next time a hurricane strikes the northeast coast (hopefully not for several decades), I’m going to read a book about the creation of the Library of Congress Classification System. Because, once you’ve learned about the history of the classification of birds, it is time to go on to the next big thing, the classification of all the knowledge in the world.

What bird books did you read during and after Hurricane Sandy?

———–

The Feathery Tribe: Robert Ridgway and the Modern Study of Birds by Daniel Lewis.

Yale University Press, 2012.

368 p., 6 1/8 x 9 1/4 with illustrations.

ISBN: 9780300175523?

Cloth: $45.00

Kindle: $26.10

A note about price: The Feathery Tribe is available in hardcover at the rather steep price of $45. This is where your local library comes in handy. And interlibrary loan. Or, you can do what I did and download a Kindle version for a little more than half that price. (Yale University Press kindly sent me a review copy afterwards.)

Photographs:

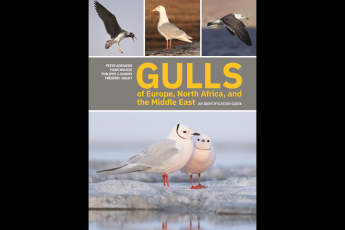

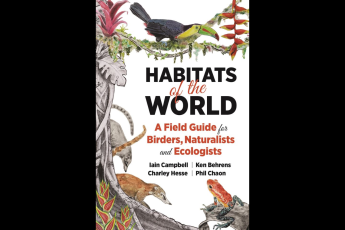

The cover photograph was provided by and is used with the permission of Yale University Press.

The photos of Ridgway’s office and Elliott Coues were downloaded from Wikimedia Commons, a source of freely available media, and are also used in the book.

The color plate from Color Standards and Color Nomenclature was obtained from the Google digital version of the book, available to the public under Google Books copyright guidelines, and is not in The Feathery Tribe.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Excellent review! It summed up some of the feelings that I had about the book. One other thing – I thought that it was often jarring to go back and forth between the overall ornithological world and the straight biography. This should have been two books.

Thanks for a nice review, Donna. Embarrassingly, I haven’t got around to the book yet, but am looking forward to it.

My favorite Ridgway color has got to be broccoli brown, encountered over and over in the emberizid accounts in BNMA.

And I hope that you’ll be writing something soon about the Biodiversity Heritage Library, one of the most important resources available to birders nowadays. Have a look here: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/creator/1444

Thanks, Corey. I think you’re right that this is really two books in one, but for some reason the move from biography to ornithological history and then back again did not bother me. Probably comes from too much television surfing. I do think there was great potential here for a psychological portrait of Ridgway and Coues’ relationship, but that was clearly not the biographical method Lewis chose to use.

Rick! I was thinking of you when I wrote this review, because I know you have written about Coues and that you are a great fan of his writing. I will be looking forward to your comments when you read this book. And, I will take another look at the Biodiversity Heritage Library, a wonderful digital repository.

Donna, thanks so much for that terrific review of my book! I’m grateful you were so thorough in your reading of it, and so thoughtful in your comments. You’re absolutely right about its somewhat ponderous nature at points. This is partly a reflection of writing a mostly academic book for a university press, but it also stems from my desire to untangle a particular story about scientific and nomenclatural life after Darwin. Parts of it are a snoozer for the casual reader, but since it engrossed me I put it down as I came to understand it.

Ridgway wasn’t the world’s most colorful guy, and his perennial shyness made him a less-than-riveting public figure. I came to feel that a strict biography of him — which was my original plan back in 2002 when I started the project — would have been pretty tedious (and even more so than the current book, which I’m sure some people find tedious anyway!).

My next book project is about Hawaiian birds and extinction, and I’ve learned a lot from my Ridgway book that’ll inform my approach to the new book, which is well underway. I may try to convince my editor to let me write it in the first person, as a kind of memoir; I’m from Hawaii, and have plenty of stories to tell.

Daniel, I so appreciate your comments on the review! As an academic librarian (my day job), I totally understand the demands of scholarly writing. There are birders out there who love the nomenclature “stuff”, and I hope my review will entice them to read The Feathery Tribe.

I think a book about Hawaiian birds is a wonderful idea, especially with the rumors going around that Hawaii may become part of the American Birding Association territory. I hope it can be done from a personal viewpoint, and look forward to reading your stories.

Donna! Thanks so much. If you’re ever down near Pasadena, come by the Huntington Library, and I’ll give you the cook’s tour of our bird holdings, which includes an original 4 vol. double elephant folio set of Audubon’s “Birds of America,” as well as Audubon’s copy of Alexander Wilson’s book “American Ornithology,” but also lots of other great birdy stuff. – Dan