Geladas are the sole survivors of a once abundant branch of primates that historically foraged across the grasslands of Africa, the Mediterranean and India. These relics of times gone by now cling to a precarious existence on the sheer cliffs of Ethiopia’s mountains, from which each morning they materialize, to forage on nearby moorlands, before disappearing down the precipices in the evening.

Male Gelada in his prime. Photo by Adam Riley

For those who have heard of these singular creatures, the name Gelada Baboon would ring a bell. However recent research has shown that they are in fact not baboons, despite superficial appearances, and they are now just called “Gelada”. This was the local name meaning “ugly” used for these primates by the people of the Gonder area in northern Ethiopia when the German naturalist Rüppell “discovered” this species for science in the 1830’s. They have also been known as Lion Baboons and Bleeding-heart Baboons, due respectively to the males’ lion-like cape and tail, and the bare patch of red skin on both sex’s chests. Their scientific name is Theropithecus gelada, the former word meaning “beast-ape” in Greek.

Gelada lip flare and yawn. Photo by Adam Riley

Geladas have numerous special characteristics including:

• sporting the largest canines in proportion to body size of any mammal;

• yet they are the only graminivorous primate (meaning they feed primarily on grass, not to be confused with a seed-eating granivorous animal!);

• they have the closest vocal repertoire to humans of any mammal;

• they have the most complex social structure of any mammal after humans; and

• they are the most terrestrial primate after humans.

Geladas spend the fist few hours of the morning grooming and socializing at the edge of their cliffs. Photo by Adam Riley

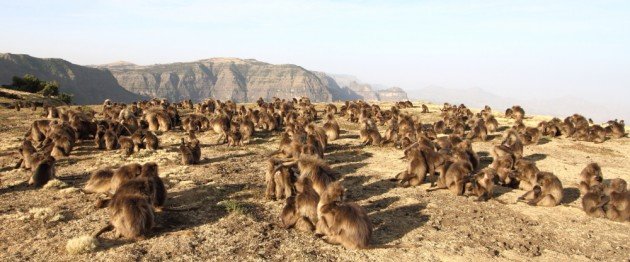

Appearances are certainly deceiving when it comes to Geladas. Their fierce physical appearances give way to a far more fascinating social structure once you spend a bit of time with them. In parts of the Simien Mountains of northern Ethiopia, from which I have just returned, Geladas have been protected from persecution for some time. This has resulted in their populations returning to natural levels and their fear of humans being curtailed. We were able to spend hours sitting right in amongst super-groups of 500-600 Geladas that just carried on with their daily business in total oblivion to our presence. These experiences were the highlight of my trip to Ethiopia and one of the most fascinating and enjoyable encounters I have ever had the privilege to experience in many years of wildlife watching.

A harem male grooms one of his females. Photo by Adam Riley

The basic Gelada social unit is a harem (or unimale group) made up of a dominant male and several females (1-12), their young and sometimes subordinate males. The next tier is a band that consists of several harems (usually 2-27), and this is the main social aggregation in which most Geladas spend their lives. Especially in the dry season, bands join together forming grazing herds, which can number up to 1,200 animals (although 500-600 is more normal.) Males that do not have attached females also form bachelor groups that usually associate around the periphery of the bands or herds. A harem system would indicate that the males gather and forcibly retain the affections of their females, as is the case with the savanna baboon species, but not with Geladas. The females are the ones that form the strong hierarchical bonds, often matrilineal, within the harems and they usually determine which male will become their harem “leader”. For males (averaging over 40 pounds and nearly double the female weight), its all about showmanship. They strut about flicking their luxurious fur capes, roaring, displaying their massive canines, chasing off rival males and generally just releasing their built-up testosterone, but back at the ranch, it’s the females that actually call the shots. In fact most of the aggression witnessed is started between females and this then draws in the males. Males maintain their relationships with their females not by dominance but by grooming them, but the females sometimes band together and attack their male if they feel he is shirking his duties by not grooming them sufficiently or not protecting them properly.

Bachelor male Geladas chase a harem male. Photo by Adam Riley

We were also fortunate to witness an amazing interaction between a bachelor group and harem males. We were attracted to a massive commotion going on the boundary of a huge herd of Geladas. Groups of younger males were racing around chasing large males, all of them making an unbelievable racket and flaring their lips which are pulled over their gums to show off their formidable teeth. Some males had climbed yellow-flowered St John’s wort trees and were leaping up and down, shaking the branches and emitting what is accurately termed a “roar-bark”. In fact, Geladas so seldom climb trees that we actually witnessed several big males falling out and others being too boisterous and breaking off massive branches, with both the branch and the monkey hitting the ground rather solidly! We subsequently learnt that this behavior had to do with challenges between dominant males and bachelor males and is how harem males show off their virility.

Gelada communications include intense staring with raised eyebrows

As mentioned earlier, Geladas spend their nights on inaccessible cliffs, where they sleep on ledges. In the morning we observed them climbing up these massive cliffs, never in a rush, as they paused to groom or just sun themselves as the mood took them. The rest of the day is spent on the plateau moorlands close to the cliffs. They seldom, if ever, venture more than 2 miles from the safety of cliffs. At first the herd gathers close to the edge where they interact in social behavior for a few hours with only intermittent feeding. Here they relax in the sun, groom each other, copulate, yawn, lip flare, head-bob, stare at each other with raised pinkish eyelids; and the youngsters of all ages enter into the most entertaining rough-housing sessions. The whole time there is a constant chatter from the Geladas with calls signifying contact, aggression, defense, reassurance, appeasement and a variety of other social interactions. In fact Gelada social studies have been of great relevance in analyzing the evolution of human social behavior.

Foraging Geladas in their typical crouched feeding position. Photo by Adam Riley

Yawning male and a female showing off Gelada’s typical buttock pads. Photo by Adam Riley

With many primate species, females indicate their sexual status with colored and swollen genitalia and buttocks, however since Geladas spend almost the entire day sitting, they have instead developed an hourglass-shaped patch of bare skin on their chests which becomes bright red and is surrounded by swollen, liquid-filled blisters when in estrus. Males sport a larger heart-shaped bare batch encircled by pale fur, that shows off their dominance status.

Portrait of a male Gelada. Photo by Adam Riley

Gelada numbers have plummeted over the past few decades due to droughts, exportation for laboratory experiments (this disgusting practice seems mercifully to have stopped) and hunting of males for their capes used in traditional dancing and coming-of-age ceremonies by the Oromo people (hunting is now also banned with a 15-year prison sentence for offenders). However the major factor is due to the rapid human population expansion in Ethiopia that has meant that cultivation (even in national parks!) has encroached on Gelada home ranges causing loss of feeding habitat and conflicts with farmers. Competition with domestic livestock has restricted some Gelada bands to poorer foraging on steep slopes. From an estimated 440,000 in the 1970’s, current population estimates range between 100-250,000. They are however classified by IUCN as Least Concern.

Photographing Geladas in Ethiopia’s Simien Mountains by Dave Semler

Although Geladas can be seen within a few hours drive from Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, the best place for spending time with these fascinating monkeys is Simien National Park north of Gonder where these images were taken.

A male Gelada mock attacks a female. Photo by Adam Riley

Leave a Comment