From Owls in the Family to Wesley the Owl, the narrative in which a human interacts with another species and learns a bit about life along the way has long been a popular and affecting one. Even many of our clumsy and destructive attitudes towards our fellow creatures — the horrors of early zoos and circuses, the irresponsible feeding of stray cats, the impulse to grab up fledglings who are just trying to get their air-legs under them after leaving the nest and ‘help’ them — often spring from a deeply rooted desire for interaction, a belief that it will lead to something profound.

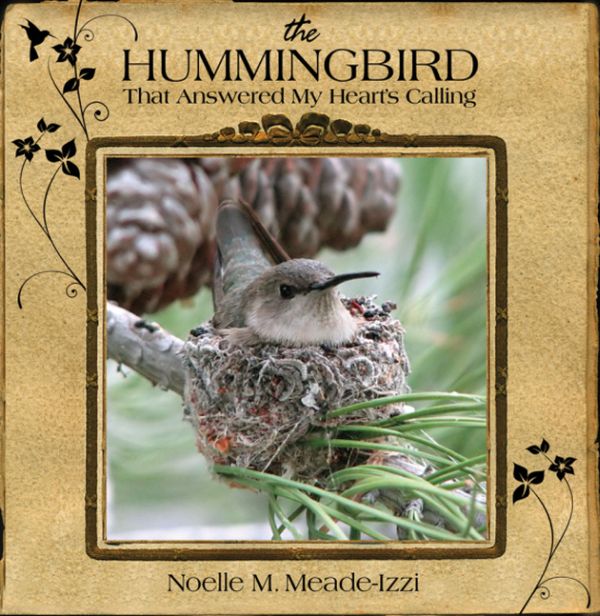

This is a story that is clearly not going away. And seen in that light, you could do worse with such tales than The Hummingbird That Answered My Heart’s Calling. Author Noelle M. Meade-Izzi takes a New Agey view that can seem startlingly self-centered (as when she states “Artemis [the hummer of the title] had showed up in my life to share a part of her world”) but what she does not do is interfere with, hold captive, experiment on, poke or prod her new ‘friend’. The closest she comes is singing to the incubating bird. This is a pretty good model of the modern environmental ethic of self-restraint and respectful watching.

That said, the book contains little that is likely to impress the seasoned birder. Meade-Izzi’s discoveries — that hummingbirds are tiny, and cute, and part of a remarkable food web that demonstrates the interconnectedness of all living things, that they can inspire a human to follow her instincts and work on contentment in her own life — are those of a nature novice, albeit a wildly enthusiastic one. The extremely short chapters, four or five paragraphs in length, don’t really allow for the development of more complex themes.

Also, as mentioned before, the narrative voice is overtly New Agey, full of assertions about the love of Mother Earth and the creative stream of all that exists — a stance unlikely to resonate with a more scientifically-oriented audience. I certainly found it jarring. And the author’s vast near-pantheistic enthusiasm for her subject is too often expressed by the addition of more words, more punctuation, more over-the-top sentences, the occasional bout of all-caps for emphasis. She shows little editorial restraint. This is a shame, because were the text less verbose, I could see the book appealing to a younger audience with more patience for the basic, the obvious, and the odd passage of imaginary dialogue between birds.

There is one significant aesthetic problem with the physical book, too. The book designer has fallen into the classic trap of selecting a beautiful, lightly textured background that works great for the abundant photographs, but combines with a slight font to make the text aggravating to read.

So, while it represents a fresh effort in a long tradition, I must say that I wished for much more from this book than it delivered.

Good review. I especially appreciate the comments about hard-to-read fonts!

Carrie Laben’s review does contain one piece of useful information concerning the “beautiful, lightly textured background that works great for the abundant photographs” but makes the font “aggravating to read.” Ms Laben is justifiably “aggravated” because she donned her scientific-oriented, birder spectacles for the light-hearted, inspiring story with “Answered My Heart’s Calling” in the title. This reviewer has fallen into the classic trap of having to trounce a story with phony evidence in order to manufacture a “critical” book review. Perhaps Carrie should relax one night, pour a local microbrew into a chilled glass, curl up next to the warm glow of her fireplace, turn on a powerful reading lamp to enjoy this spunky, fun, heartwarming, thought provoking gift book in a “different light.” The reviewer claims Meade-Izzi’s voice is overtly New Agey, full of assertions about the love of Mother Earth and the creative stream of all that exists” which jarred her with “little editorial restraint.” Personally, and with a scientific eye, I found the author’s portrayal of “interconnectedness” in Nature and the Universe refreshing and in line with widely accepted views on merging spiritual beliefs and proven science.

I stepped back from my ego and narcissism and enjoyed this little book…a book written with artistic flair, and obviously not meant to be a scientific, birding journal. I recommend this book for those willing to enjoy Meade-Izzi’s energetic writing style through a lens that enunciates her journey with once-in-a-lifetime imagery. And, by the way, anyone facing “empty nest syndrome,” this book is for you!