Long before I moved in New Zealand, or visited or even knew much about the wildlife here, way back then I knew about the Poor Knights. I knew about them because I was a scuba diver. I started diving as an undergraduate in Southampton, and being unable to travel frequently at the time I consumed diving magazines and dreamt of visiting far flung destinations (something still do, actually). The Poor Knights were internationally famous and often turned up in those inevitable lists of “top places to dive” along with Cocos Island, Sipadan, the Great Barrier Reef, Truk Lagoon, Bikini Atoll and the Blue Hole in Belize. In fact no less a figure than Jacques Cousteau rated it in his top ten, and he was no slouch when it came to diving! I’ve subsequently managed to dive in some spectacular destinations, including Turneffe Atoll in Belize, the Great Astrolabe Reef in Fiji, the kelp forests of Monterey and the wreck of the President Coolidge in Vanuatu. In New Zealand I’d even dived the astonishing Milford Sound in Fiordlands National Park, but I didn’t make it to New Zealand’s most famous dive site until January of 2009.

My first real connection to the islands predated that trip however, and it is a connection that anyone who has gone out seabird watching on the West Coast of the US might feel. Amongst the assortment of southern hemisphere petrels and shearwaters that travel up to America’s coasts during the northern summer, sometimes in monumental numbers, are one particularly distinctive species. Buller’s Shearwaters are perhaps the easiest of the shearwaters to identify due to their distinctive m-shaped makings on their back, and anyone that has tried to separate Sooty Shearwaters from Short-tailed Shearwaters at sea will appreciate an easy ID! These shearwaters don’t just come from New Zealand though, the come from the Poor Knights, and the Poor Knights only.

Buller’s Shearwater (Puffinus bulleri) not showing off it’s distinctive wing pattern.

Getting to the Poor Knights involves a day-trip out of the small fishing port of Tutukaka, and straight out of the harbour we had our first wildlife encounter, a pod of Bottlenose Dolphins that swam around the dive boat. As we got closer to the islands (the trip takes around an hour) large groups of seabirds can be seen on the water, dominated by Buller’s Shearwaters and Fairy Prions, but also mixed in with White-fronted Terns and Australasian Gannets. Because the conditions were good we started the day diving a site called the Sugarloaf, a mass of rock at the southern tip of the Poor Knight chain. The exposed location meant it can only be dived during calmer days. but also promised a great number of fish along the walls. As we prepared our gear I could watch terns and Welcome Swallows of all things flying above the water next to the rock, but most people were anxious to get in the water. We entered the water at the southern tip of the island above a slope of massive kelp, and from there slowly made our way to the western side of the rock where the sheer wall mixed encrusting organisms among the kelp.

Grandfather Hapaku or Eastern Red Scorpionfish (Scorpaena cardinalis) hiding on the wall

A stunning nudibranch (Tambja verconis) Can you see the tiny fish too? Click to enbiggen.

Red Pigfish (Bodianus unimaculatus)

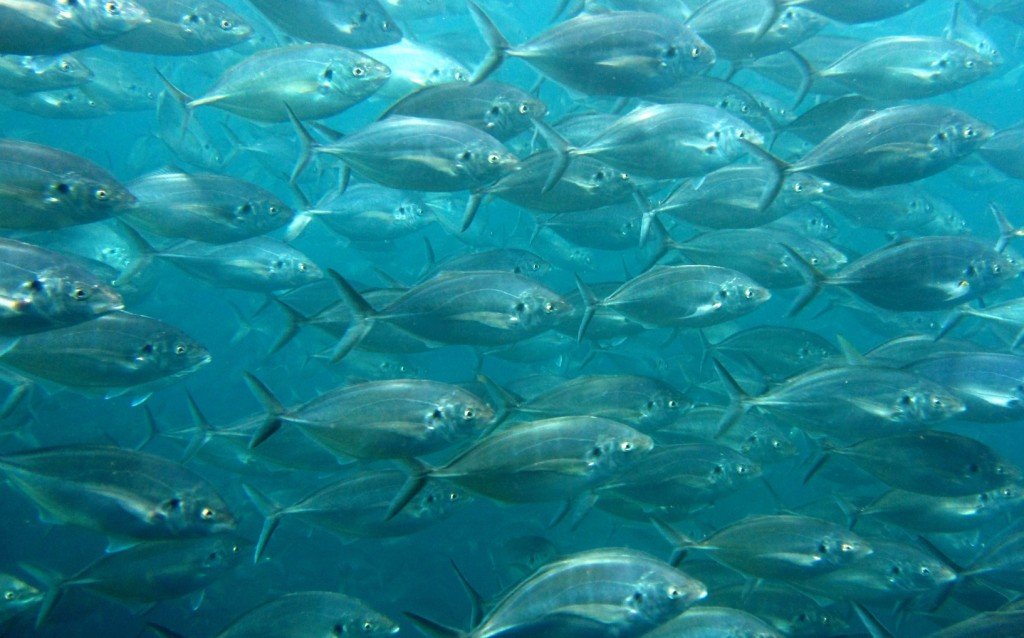

Turn away from the rock wall and face off a wall of predatory Trevally (Carnax lutesc)

The walls also had a number of moray eels, small triplefins, sponges, tunicates, anemones, and the wonderful Lord Howe Coralfish, a tropical species in the butterflyfish family that reaches the edge of its range in the Poor Knights. Also present off the wall were the large predatory Kingfish. Before you know it your time is up (actually, you should know it, keeping an eye on your time is vital, as keeping an eye on your air) and we were at the surface rolling round in the swell next to the boat. This is where the day took a bit of a bad turn for me, I’d (without thinking about it) been skip breathing (pausing between breaths), which had given me a headache. Then there had been a delay once I was on the boat, meaning I was standing around in the swell with all my heavy gear on, and had caught a bout of sea sickness. The combination of the two was very unpleasant and I missed most of the cruise through the islands and the large numbers of seabirds there. Fortunately we stopped for lunch in a sheltered bay and I recovered in time for my next dive.

The second dive site was under the Eastern Arch inside the main group. The arch was massive, and after dropping down into a kelp bed we soon found ourselves going along a kelp-free wall. The water under the arch was clear and with the highly directional light the whole effect was like being in a massive submerged cathedral.

Blue Mao Mao Arch from the surface (not the one we dived)

A whole mess of Demoiselles (Chromis dispilus) and Blue Maomao (Scorpis aequipinnis) in the catherdal like arch

Another nudibranch (Ceratosoma amoena). They’re kind of the pittas of the diving world, only easier to find.

Diving rewards careful searching of scenes like this. Where birders want big telephoto lenses, divers prefer macro lenses. Can you see the Blue-eyed Triplefin (Notoclinops segmentatus)?

Short-tailed Stingrays (Dasyatis brevicaudata) can mass in huge numbers in the archways, although we only saw a few on our visit.

Short-tailed Stingrays (Dasyatis brevicaudata) can mass in huge numbers in the archways, although we only saw a few on our visit.

The Poor Knights certainly lived up to their reputation, and to my mind are arguably an essential stop on a visit to New Zealand, even if you only came looking for wildlife of the feathered kind.

***

The copyright of all the underwater images belong to my diving companion and friend Ingrid Knapp and are used with her permission. Thanks to her, Abi, Gareth and Tron for a great trip!

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

From my experience snorkeling in Hawaii, I can see how sealife identification is a similar thrill to birding. Geez, Duncan, now I’m gonna have to take up diving. Awesome pictures!

I think more birders should try diving. The two activities hit many of the same notes, with the added bonus that wildlife under the water is often much more approachable.

Oh man. Nudibranchs.

Unbelievable, just the biodiversity of this place. I pour over diving magazines, also, but have never heard of this place. Definitely going to be on my bucket list for the future.