Some of the most popular birds in the world are parrots, particularly the large, multi-coloured Ara Macaws. Found throughout South America in ever-dwindling numbers these extremely beautiful birds – threatened by habitat destruction and collection for the wild bird trade – are often difficult to see and hard to find. UNLESS that is you get yourself down to the internationally-renowned Tambopata Research Centre in southern Peru where literally hundreds of macaws (and other parrots) congregate around a 50 meter high clay bank. It is, as the Tambopata research website says:

…a unique forest environment, with the highest concentrations of avian clay licks in the world. A range of animals come to satisfy their need for salt or the soothing effects of the clay along the river banks of the region. The experience is one of the ornithological highlights in the world.

Lucky for us, world-traveler Tim Ryan of From the Faraway, Nearby was good enough to provide a profusely-illustrated account of his visit to Tambopata as a volunteer in 2008. Is this one of the ornithological highlights on the planet? Read Tim’s account and enjoy his (and the Tambopata Macaw Project’s Alan Lee’s) photos judge for yourself…

(NOTE: we first published this post in January 2009 but have to run it again because it is so good!)

‘Licking Clay’

Text and Photographs copyright T. R. Ryan (From the Faraway, Nearby), unless indicated otherwise

Red-and-Green Macaws Ara chloroptera. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

The 3:45 am knock on the bamboo wall of my room has now become an appreciated morning ritual but largely unnecessary – the pre-dawn clamor of the jungle has already begun to surge and swell at the prospect of forthcoming daylight. The symphony of insects, frogs and birds crescendos at this dark hour and renders sleep nearly impossible- all the noises associated with big city living are here and matched, sound for sound.

Thirty minutes later I find myself navigating a jungle path in pitch black darkness trying my very best to juggle a dizzying assortment of scopes, binoculars, cameras, camp chairs, identification charts, clipboards, and datasheets, along with enough food and water for an eight hour excursion, while successfully staying upright like the biped I evolved to be as I maneuver over rocks and roots and through the mud and muck of a rainforest floor.

At this hour I am a reluctant, under-caffeinated sherpa – and concentration must be given to the dangers of the footpath ahead. The swing and sway of my headlamp picks up a highly venomous wandering spider scuttling off to one side, the catlike eyes of a deadly parrot viper coiled on a branch just ahead and a long column of army ants marching resolutely under foot. This is all in a day’s work and a typical morning here at the Tambopata Research Center in the Madre de Dios district of Peru where, on behalf of the conservation agency Earthwatch Institute, I have come to volunteer for two weeks for the Tambopata Macaw Project.

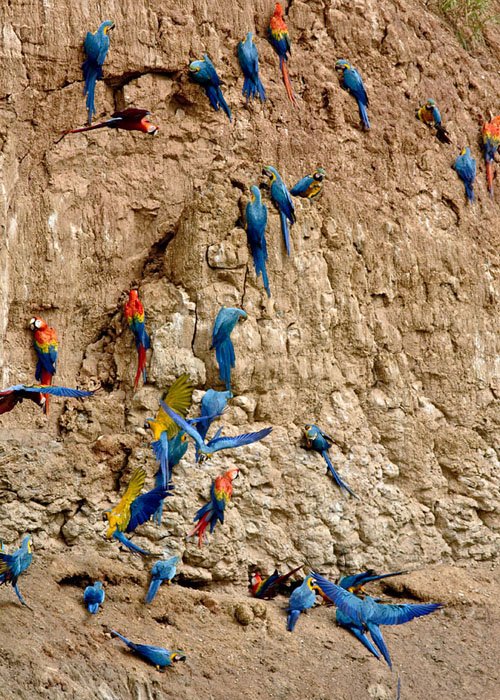

The field site I am assigned to is located in one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world and home to a particularly rich avifauna that numbers well over 500 species. What makes the site even more compelling is the fact that it is home to the world’s largest known avian clay lick – visited each morning this time of year by hundreds of brightly colored macaws and parrots.

Scarlet Macaw Ara macao. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

The Tambopata Macaw Project was started in 1990 in an effort to better understand the basic ecology and natural history of the area’s rapidly disappearing psittacine population. The primary reasons for the decline of macaws and parrots are many but habitat loss due to logging; clear cutting for crops and cattle ranching; and capture for the pet trade rank among the most threatening. These threats are further exacerbated by the naturally low reproductive rates of these cavity-nesting birds.

The long-term objectives of the project are varied but include the monitoring and observation of macaw nest sites, developing and testing nest boxes, recording the varied patterns of clay lick use by large macaws and parrots and better understanding the impact of tourism to this world famous clay lick.

Under the expert guidance of project director and locally infamous snake and bird-whisperer Alan Lee, my responsibility as a volunteer here is to observe and monitor the 15 species of macaws and parrots that come to the lick, or colpa as its more commonly called in the local Quechua language, each morning to eat clay. That’s right – birds eating clay. Geophagy, the intentional consumption of soil by vertebrates, has long been documented in a number of bird and mammal species – including wide-spread use by humans – which consume soil to increase absorption of certain minerals not naturally occurring in the local diet.

Scarlet and Blue-and-Yellow Macaws Ara macao and A. ararauna. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

The reason for clay-lick use by the macaws and parrots observed at Tambopata is a subject of much discussion. Many of the fruits, seeds and flowers that make up a significant part of a macaw’s diet in this part of the Amazon basin have evolved with naturally occurring toxins designed for the plant’s self-protection. The clay consumed at the colpa contains chemicals that bind with these ingested alkaloids thus neutralizing their toxicity. Years of follow-up research conducted by one of Earthwatch’s principal investigators on the Tambopata Macaw project, Dr. Don Brightsmith, shows, however, that within the study area of the clay lick the birds tend to choose the soil with the highest sodium content over soils that are best for neutralizing toxins. There is a high degree of correlation between both theories and ongoing research allows for the possibility that macaws and parrots receive multiple benefits from eating clay.

Chestnut-fronted Macaws Ara severa. Photo copyright Alan Lee – Tambopata Macaw Project

By 4:40 am we are positioned, stop watch and data sheets in hand, in a natural blind on an island that rises unexpectedly out of the slow moving Tampobata River 150 meters across from the colpa. And we wait. By 4:45 am the sun rising through the jungle canopy marbles the 50 meter high clay bank with an eerie, diaphanous light and, for a moment, the world turns pale pink. As if cued by this iridescent light flooding over the tree line, several dozen Chestnut-fronted Macaws sweep in from the west followed closely by a large flock of Red-bellied Macaws and both scatter throughout the tree canopy in front of the lick.

Blue-and-Yellow Macaws Ara ararauna. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

Seconds later the sky from all sides is flushed full of screeching, screaming, ‘graaawking’ Scarlet, Blue-and-Yellow and Red-and-Green Macaws. By twos and fours they arrive and scatter in small groups among the canopy to their favorite perches in iron, cecropia and aguaje palm trees. The crowd of macaws is soon joined by parrots arriving as if on cue and bearing their colorfully named body parts: Yellow-crowned, Blue-headed, White-bellied, Orange-cheeked, and Mealy – followed by two species of parakeets – Dusky-headed and White-eyed.

Scarlet Macaws. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

The time is now just shy of 5:00 am and what I behold in front of me is considered one of the great spectacles of the natural world. Hundreds of riotously colored birds representing 14 species of macaws and parrots flock and frolic together in less than fifty meters of forest canopy. The cacophony and color of this much birdlife socializing at once overwhelms the senses and boggles the mind of even the most intrepid birder.

Each bird, regardless of species, seems perfectly content to wait for the other to make the first move toward the colpa. By 5:10 am the parrots and macaws take to the air in their own collective groups and begin what is described as “the dance” – sweeping and swooping in circular patterns between the canopy and the colpa eyeballing any potential predators and readying to perch cliff-side to start eating clay. A pair of brave chestnut-fronted macaws lands on the lick first and after a brief, secondary pause most all of the birds alight and jockey for space on the colpa and begin eating clay by the clawful.

Blue-and-Yellow Macaws Ara ararauna and Mealy Amazons Amazona farinosa. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

Every five minutes the stopwatch vibrates with a barely audible beep and every five minutes my assigned partner and I record the number of each species on the lick. The data we record is yet another entry that will join the carefully logged data sets from over a thousand mornings of clay lick observation, resulting in what Alan Lee speculates might well be the largest set of parrot data ever assembled. This data has gone a long way in helping the experts formulate concise and workable parrot conservation plans that merit serious consideration by both the local community, the ecotourism community and the Peruvian government.

Scarlet and Blue-and-Yellow Macaws Ara macao and A. ararauna. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

The birds will spend the next thirty to forty-five minutes on the colpa mining clay while remaining vigilant for any number of opportunistic predators that also frequent the area.

Photo copyright Tim Ryan

From time to time the unexpected crash of a falling cecropia leaf or the long shadow of a Roadside Hawk will flush the entire wall of birds into the air and we grapple for our cameras as the sky continually explodes with a rush of sound and color. Even Yellow-headed Vultures Cathartes melambrotus receive a quick escort out of the area.

Photo copyright Alan Lee – Tambopata Macaw Project

In time the macaws and parrots ebb and flow away from the colpa. By 8:00 am little remains but a solitary Common Guan or Purplish Jay weaving through the brush at the top of the cliffs. In a few hours the larger macaws will return, this time by the dozens, and several hundred Cobalt-winged Parakeets will arrive for their afternoon snack of sodium rich, toxin-binding clay.

We continue to monitor the lick for any unexpected visitors. We watch. We wait. We wonder. Between the timed intervals and the waiting we discover other marvels of the forest that ease out of the shadows of the day: the human-like whispers of a Razor-billed Curassow, a lek of Black-fronted Nunbirds hawking insects above our blind and a colony of Russet-backed Oropendolas tending to their intricate woven nests.

Russet-backed Oropendola Psarocolius angustifrons. Photo copyright Tim Ryan

At noon its time to pack up and complete the notes for the day. In the distance I can just begin to hear the rattling groan of the longboat sent to ferry us off the island and back to the lodge with all our gear. I take a last look at the colpa now blazing in the sun with the odd scarlet or blue-and-yellow macaw still perched in the canopy in one of the earth’s wildest places and I am overwhelmed with gratitude for the opportunity to contribute toward the preservation of these beautiful birds.

Looking at the staccato-like entries of my field notes one last time I am aware that my tiny contribution during these two weeks is extraordinarily minute compared to the months and years of dedication many here have contributed. And even though I have paid for this experience in the form of a much-needed donation, it still feels oddly like a privilege to be here working with people like Alan Lee – people from all walks of life who are dedicating their lives to saving these beautiful birds and protecting this extraordinary place in the world. I consider their efforts a remarkable generosity and that generosity serves as both inspiration and reminder that I must always endeavor to move through this world with greater purpose. Glancing back once more, I make a silent promise to return.

Interested in volunteering? The thousands of hours of observations that have been added up over the years would not have been possible without the help of the many volunteers and assistants who have offered their time and energy in the cause of science and conservation. Volunteers are one of the most important aspects to the project. There are no qualification limitations, although most volunteers have come from a biological or environmental background. All applicants are welcome, as we can find a role for most people, be it data entry or tree-climbing. As this is an ongoing project we accept applications and volunteers throughout the year. Please go to http://macawmonitoring.com/tambopatamacawprojectvolunteering.html

Interested in volunteering? The thousands of hours of observations that have been added up over the years would not have been possible without the help of the many volunteers and assistants who have offered their time and energy in the cause of science and conservation. Volunteers are one of the most important aspects to the project. There are no qualification limitations, although most volunteers have come from a biological or environmental background. All applicants are welcome, as we can find a role for most people, be it data entry or tree-climbing. As this is an ongoing project we accept applications and volunteers throughout the year. Please go to http://macawmonitoring.com/tambopatamacawprojectvolunteering.html

So nice to see such a well written post about the Tambopata clay lick and glad to see information about volunteering. Birders with the time and energy to do it should jump at this amazing opportunity- you get to see the clay lick action every day, work with wonderful people, might see a jaguar, Giant Otters, etc., etc.. Oh, and you also get to bird in fantastic Amazonian habitats with some of the highest bird diversity in the world. For example, regionally high diversity + boreal migrants + austral migrants = well over 600 species recorded from Puerto Maldonado up river to the research center. And that’s just in the lowlands!

Nothing like waking up in those forests to the screeches of macaws, odd gurgling sounds of nunbirds, trills of antbirds and woodcreepers, and melancholy songs of tinamous.

Excellent article on the Macaws of Tambopata! i am very interested in volunteering at the research centre over July and August 2011. I was wondering if you know the contact details of the macaw project? because i am not sure if i am emailing the wrong address?

Many thanks

As a birding tourist, I must say that this is a must not miss oppotunity. The vast numbers of birds that visit this these licks each day is incredible. The noise as it builds is phenominal and the variety of small birds birds, capabara, monkeys and caymen make it a real experience. If you get a chance go!!

Hi, Are binoculars with 8x magnification good enough to see the birds at the TRC clay lick?

Is the facility open to the public or can a person make a reservation ? I am a wildlife photographer and have an interest in tropical birds particularly Macaws .

Jerry Fleck

k0du@yahoo.com

Grand Junction , Colorado USA

Thank You !