The Nature of the Meadowlands is a celebration of an environmental success story. I think every naturalist in the United States knows the outlines of this urban tale: The pristine marshes of New Jersey are poisoned by pollution, toxic waste, pig farms, and probably every single way in which human beings can destroy the environment. Traveling through northern New Jersey becomes the subject of jokes and the cornerstone of disparaging remarks about the state, reaching its zenith in The Sopranos, which names an early episode about a mock mob execution “Meadowlands” and features North Arlington’s Pizzaland in its opening sequence. (Bruce Springsteen lyrics about “the swamps of Jersey” from his popular song Rosalita didn’t help matters.)

Enter the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission in 1969, created by state legislation, renamed the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission in 2001. With help from federal grants, state agencies, supportive legislators, and a devoted, knowledgeable staff, the Meadowlands slowly becomes a habitable place for birds, mammals, and other wildlife, a place where people can go to enjoy beauty in the middle of the densest populated area in the country.

This is the fable of the New Jersey Meadowlands and it is all true. The Nature of The Meadowlands, a photographic book by Jim Wright, presents the tale, and though you may be thinking that you live in Ohio, so this book is not for you, it is worth paying attention. The book serves as a model of how our environmental success stories can be presented to the non-birding public, the citizens and legislators who are responsible for funding conservation projects and habitat protection.

When I first started birding New Jersey, I didn’t really know where the Meadowlands started and stopped. I’d see marshes filled with egrets that seemed to go on forever as I drove down Turnpike, and there was Giants Stadium, of course, but there seemed to be other areas that were also called Meadowlands. Fortunately, the book starts with an introduction to the places that comprise the 30.4 square mile area along the Hackensack River. There is DeKorte Park, a great site for ducks in winter and butterflies in summer, all seen against the backdrop of lower Manhattan; Kearny Marsh, currently home to an American White Pelican; Laurel Hill, Secaucus, where Common Ravens are sometimes seen next to the Turnpike, and Losen Slote Creek Park, where flocks of Common Redpolls were sighted last month. The New Jersey Meadowlands covers parts of 14 municipalities in Bergen and Hudson Counties, in northern New Jersey, including nine parks and natural areas.

Wright traces the history of the area, from its original volcanic creation, through the growth of fragrant, rot-resistant Atlantic White Cedars and then the felling of the cedars by settlers, and the start of the “reclamation” of the marshes. The “Dark Ages” really begins after World War I, when the marshes and the Hackensack River become the dumping ground for the sewage and garbage of the growing urban areas around it. The details of the myriad ways in which the land and water were poisoned—toxic substances called leachate resulting from unregulated landfills, industrial sewage, mercury, PCBs, manure from Secaucus pig farms—are horrifying. Wright combines material from reports about the pollution with descriptive quotes from people who grew up in the area. The books provide the facts, the interviews give them an immediacy. This really happened, we created a landscape of toxic horror.

The chapter on Turning the Tide is happier, if much briefer, focusing on the Commission’s strategy of recognizing wetlands as a natural resource, working with the Department of Environmental Protection to de-pollute the Hackensack River, and restoring many of the wetland areas. The photograph above shows kayakers going past plugs of Spartina, planted by hand to replace invasive Phragmites. There is a lot more to this story, I’m sure. Wright says little about the politics behind the passage of the Hackensack Meadowlands Reclamation and Development Act in 1968, nor does he delve into the founding and development of the resulting Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission. And, as much as I’d like to read about that story, it really is a tale for another book. This is a coffee table book, not an historical analysis.

About half of The Nature of the Meadowlands is devoted to just that, the birds, mammals, butterflies and other bugs that now populate the wetlands. Located along the Atlantic Flyway, 280 avian species live or migrate through the Meadowlands, including “almost half of the 77 birds on New Jersey’s list of birds that are endangered, threatened or of special concern.” Bird banding helps Meadowlands naturalists analyze how to manage the landfills and wetlands for their benefit. Resident birds, such as this Gray Ghost (Northern Harrier) photographed hunting near Disposal Road one winter by Ron Shields, are well represented, as are migrants and rarities. I was very happy to see photographs of two birds I’ve viewed at DeKorte Park, the 2009-2010 Northern Shrike and 2009 Northern Wheatear, as well as birds that I’ve missed. (I really don’t bird Northern New Jersey as often as I should.)

Mammal life has been harder to find and photograph. A camera with a motion-sensitive shutter had to be used to prove that there are coyotes living in at least one closed landfill. And, Wright describes a recent project designed to find out if there are bats in the Meadowlands using acoustic detectors. (There are, at least 2 species, thank goodness. Bats eat mosquitos.) In a lovely and loving end to the book, Wright goes through a year in the Meadowlands month by month. Some of the book’s best photography can be seen here, such as the Semipalmated Sandpipers below, migrating through in late August.

Jim Wright is communications officer for the Meadowlands Commission, author of the Meadowlands Nature Blog, three other coffee table books, and of a birding column in The Record, a northern New Jersey newspaper. He is also an active northern New Jersey naturalist who leads nature walks at DeKorte Park and who is involved in the stewardship of the Celery Farm, another very birdy northern New Jersey natural area. Yes, this is an “official” book, but Wright’s affection and commitment to the area is very authentic. The story is illustrated with 158 color and 17 black-and-white images, including archival photos, such as the one below of dikes being built for mosquito control (a futile effort), reprints of paintings of the early, pre-industrial Meadowlands, and artistic depictions of a prehistoric Meadowlands. Most of the photographs are by Wright and North Jersey photographers Ron Shields and Marco van Brabant, with contributions from additional local photographers, such as Stephen McNamara, a manager on a wetlands remediation project who just happened spot a rare (for New Jersey) Harp Seal and photographed it with his cellphone.

Materials at the back of the book include a Bibliography of books and periodicals, a map of the Meadowlands, and an Index. The Bibliography is exactly what a bibliography should be, a list of sources used. I wish it had been expanded into a List of Resources; there has been a lot written about the Meadowlands, including an award-winning children’s book entitled Meadowlands: A Wetlands Survival Story by Thomas Yezerski (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011). The Index is adequate, listing species and names. I was very surprised not to see any reference at all to Jim Wright’s excellent Meadowlands Nature Blog. Did I miss this? The blog is a great resource to birders who need an introduction to birding the Meadowlands or who just want to keep up with what is going on there, what good birds are being seen where and by who and how to get there.

The Nature of the Meadowlands aims to celebrate the accomplishments of the Commission, its employees and associates, and to educate people about the importance of its environmental work. The book succeeds very well as a lively, colorful presentation of the Meadowlands’ natural history and hopeful present, covering the history, environmental work, and natural highlights of the area in simple, readable prose. After its publication, the Meadowlands encountered another threat, this time a natural one. Super Storm Sandy dropped hundreds of tons of debris on its natural areas, destroyed trails, trees, and equipment, and caused the closure of its parks. But, as Jim Wright observed in his blog, the Meadowlands has gone through “unprecedented environmental degradation for decades” and it will survive Sandy. Already, most of the natural areas and parks have been re-opened and great birds are being seen there. I hope that the publication of this book helps New Jersey residents value the miracle that is the restoration of the Meadowlands as much as I know birders already do.

All photographs are used with the permission of the publisher.

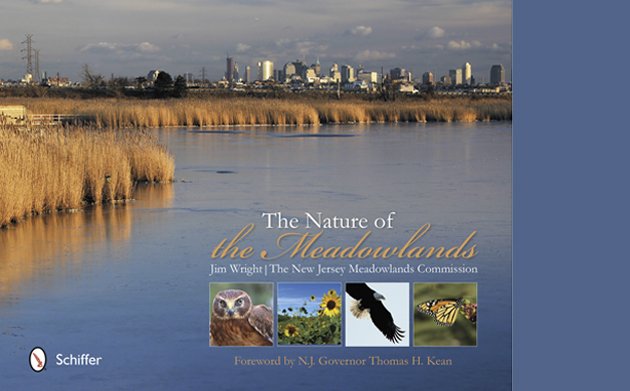

Cover photograph by Marco Van Brabant.

View of the Meadowlands, Laurel Hill, Secaucus, p. 32 by Marco Van Brabant.

Kayakers, Richard P. Kane Natural Area, p. 51, by Jim Wright.

Northern Shrike, p. 69, by Ron Shields.

Gray Ghost, p. 63, by Ron Shields.

Semipalmated Sandpipers, p.112, by Jim Wright.

Meadowlands Mosquito Dike, p.42, from N.J. Meadowlands Commission Archives.

The Nature of the Meadowlands

by Jim Wright and The New Jersey Meadowlands Commission

Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 2012.

128 pages; 8.7 x 0.8 x 11.3 inches.

ISBN-10: 0764341863

Thank you so much for this review, Donna! It is extremely important to raise awareness of these success stories in order to inspire more people to DO SOMETHING!

So glad you enjoyed the review, Cristina. I think this book will really raise the consciousness of people in New Jersey (and elsewhere) who don’t know the history of the Meadowlands. Which will definitely be in the media a lot next year, when it hosts the Super Bowl!