It is the 100th Anniversary of the extinction of the species known as the Passenger Pigeon and writers are paying attention. Three books will have been published about the Passenger Pigeon by the end of 2014: A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction by Joel Greenberg, The Passenger Pigeon by Errol Fuller, and A Message From Martha: The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and Its Relevance Today by Mark Avery. This is in addition to the many articles and exhibits and even film devoted to the bird, one of the few species whose death was witnessed and noted down to the exact day, Tuesday, September 1, 1914 (though there is some question about the exact time).

And, when you think about it, it is pretty remarkable that anything new can still be said about the bird. We already have descriptions of the huge flocks as they appeared to Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon; we can view contemporary drawings and paintings of the bird by Wilson, Audubon, and less-known artists. We have photographs and newspaper obituaries of Martha, the last living Passenger Pigeon, who died after a lifetime in captivity, mostly in the Cincinnati Zoo. We have a lot of source material. What is amazing is that each of these three books is very different in content and tone. It turns out that there are new things that can be learned about extinct birds, and that even if the conclusion is obvious–the bird is gone, there is no time machine and we can’t change that–the way in which it is presented can differ as well. A Feathered River Across the Sky was reviewed earlier this year by Carrie, so this review will focus on The Passenger Pigeon and A Message From Martha.

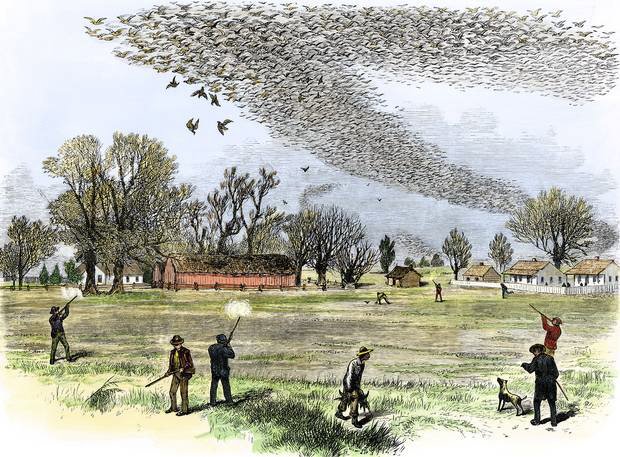

“Winter Sports in Northern Louisiana: Shooting Wild Pigeons.” This illustration from The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (July 1875), drawn by Smith Bennett, is included in both The Passenger Pigeon and A Message From Martha.

Errol Fuller’s The Passenger Pigeon is a beautifully illustrated, elegantly written “celebration” of the passenger pigeon and the artists who illustrated and photographed the species. He remarks that of all the creatures that have gone extinct, “there is one that stands out from the rest, a story so remarkable, so intense, that its elements strain credibility to its limits.” And, Fuller should know; he has spent his career producing books about extinct birds and mammals, including the recent Lost Animals: Extinction and the Photographic Record, from his home in England. (Fuller is also a photographer, but his web page notes that he seldom takes photographs of birds or animals.)

Fuller relates the story of the Passenger Pigeon in almost mythic language, describing first what it must have been like to witness a flock of Passenger Pigeons coming in to feed on your crops: hearing the drumming of the wings, seeing the enormous number or birds forming a solid, dark cloud, seeing the trees in the orchard falling under their weight as they land, then three days later mourning the destruction of your crops after they leave. It’s an effective introduction. We immediately get a sense of the pigeons’ abundance, beauty, and danger to human activity. The imaginary scenario is clearly taken from eyewitness accounts, but sources are not footnoted. This is not that kind of book, as Fuller makes clear from the beginning.

He has clearly done his research, however, and easily weaves together facts from various sources, citing scholarship, including Greenberg’s 2014 book, for major contributions to the current body of knowledge, . We find out what Passenger Pigeons looked like (larger than Mourning Doves and more brightly colored), and how they lived and their history with North America’s new European settlers, later with farmers and hunters; the three-fold reasons for their extinction–extreme killing, habitat loss, and the bird’s need to exist in vast colonies; and finally, the sad captive lives of the last Passenger Pigeons and what was done with their bodies. It is a haunting tale, and if you want a readable, engrossing but not lengthy account, I highly recommend this book.

The text is framed and expanded with a wide variety of illustrations: drawings from 19th-century magazines, paintings executed by naturalists who actually saw Passenger Pigeons (Wilson, Audubon) and those who didn’t (Fuertes and many others), photographs of captive birds, photographs of preserved birds, even sheet music representing one naturalist’s impressions of the sounds of the captive Passenger Pigeons. Every illustration is carefully positioned and identified, with attention given to the artist or photographer. Chapter titles are given 2-page spreads, with relevant illustrations that communicate better than words the author’s feelings and thoughts. The chapter on Martha, for example, just shows a close-up of her stuff body–not the whole body, the torso and tail–against an almost-black background. Can I say that this is a beautiful book? I feel like I say that a lot in my reviews, but I’m always struck when I encounter a book that is as lovingly put together as this one has been.

For Fuller, the way an extinct bird is portrayed is just as important as the bird itself, maybe even more important because this is the only way we will know the bird. And so, we get a chapter on “Art and Books”, about pictorial and textural depictions of the Passenger Pigeon. This was by far my favorite chapter, and, I think, the most unique one in the roster of books and articles coming out on the Passenger Pigeon this year. The survey of art and books is by necessity selective, but fun. Everyone knows Audubon’s famous illustration, but how many know that it has been harshly criticized for not being realistic? Fuller adores this picture (it is the cover of his book), and accuses its detractors of “pendantic ornithology.” (I love that term, and may adopt it for future use.) It is the vision that counts!(To get an idea just how prevalent Audubon’s depiction is in our public consciousness, just Google Audubon and “passenger pigeon”. The illustration adorns t-shirts, belt buckles, phone cases, aprons, mugs, computer bags, you name it.)

Fuller also presents modern conceptions of the Passenger Pigeon, including these two striking images by Canadian artist Sara Angelucci. She portrays humans merged with Passenger Pigeons; the images are then framed to look like 19th century calling cards. They are from a series called Aviary. I don’t know quite what she is trying to say, but they do make you stop and look and think.

The “Quotations” chapter presents extensive quotations from notable observers of Passenger Pigeons, including Audubon, Wilson, and James Fenimore Cooper. “Further Reading” is a nicely selected list of books, though I would also like to have seen links to books that are available online. And, then there is the Appendix: “A Magnificent Flying Machine: The Anatomy of the Passenger Pigeon” by Julian Hume, the British paleontologist who has written extensively on the Dodo. This bit of science is a nice final counterpoint to an account that has emphasized art, history, and literature. Fuller has not preached about the evils of the human practices that killed and dislocated the Passenger Pigeon; he hasn’t moaned and groaned or sentimentalized. I think this is one of the reasons I enjoy reading his books. He effectively brings his point across by presenting facts and images and a little bit of hard science. He presents the story of a species that evolved uniquely, lived an abundant existence in a utopian world of vast forests, and which, sadly, could not exist in the world we have today.

It is disjointing to go from The Passenger Pigeon to A Message From Martha. Written by Mark Avery, Conservation Director for the RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) for nearly 13 years, this book explores the reasons for the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon from the point of view of the outsider. Avery states that this is a “very American extinction” (p. 8) that could not possibly happen in Europe. I understand why he writes this; the speed at which billions of Passenger Pigeons disappeared is scary, far slower than the whittling down of bird numbers in Europe over centuries. Still, I can’t help thinking that there is some parallel between the mass slaughter of the Passenger Pigeon in 19th-century North America and the mass slaughter of songbirds in southern European countries today. In both countries, birds have been killed for reasons of food, commerce, and sport.

The book is divided into several distinct parts: several chapters that analyze the biology and life style of the Passenger Pigeon and reasons for extinction from biological and ecological viewpoints; a chapter on Avery’s 5-week pilgrimage to the United States to see where passenger pigeons lived and died; a strange chapter that lists in a chronology the U.S. historical events that occurred during the lifetime of a woman named Martha, who died the same day as Martha the Passenger Pigeon; a tortured chapter on the good and evil resulting from the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction and lessons to be learned for the future, and, finally, the lessons Avery himself learned from his U.S. journey, written up in diary format. It is a hodgepodge.

Avery offers some interesting insights into the biology of the Passenger Pigeon. Amazingly, with all the historical eyewitness accounts of the species, there are things we do not know for sure. How many eggs did a pigeon lay? How many times did it nest? Avery points out that these are important questions when figuring out the exact reasons for extinction; we need to know numbers and which numbers were sustainable. He reasons out answers to both questions, finally stating that, despite what many eyewitnesses wrote, the birds had to have laid more than one egg and that the birds had to have nested more than once a breeding season. He also analyzes the Passenger Pigeon’s relationship to their main food source–beech mast, oak acorns, and chestnuts, asking how many trees were required to maintain the billion bird flocks. These are meaningful contributions, but they get lost in Avery’s systematic, verbose writing style. These are arguments better presented in ornithological papers or a scientific monograph than in a popular book.

Avery’s trip through Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania and New York holds more promise. I enjoy stories of naturalists on the road and I think other birders do too. But, there is a difference between a birder looking for live species and a conservationist looking for reminders of an extinct species. The story of Avery’s search for some kind of contact with the world of the Passenger Pigeon, the intensity of his visits to Hardinsburg, Kentucky, where Audubon saw a billion pigeons darken the skies; the Cincinnati Zoo, where Martha lived and died; the Ohio History Center, where Buttons, the stuffed pigeon shot by a boy, is exhibited; and even Mio, Michigan, spring home of the Kirtland’s Warbler, a species that is not extinct, are lost amongst the details of Avery’s motels, breakfasts, conversations with waitresses, and overheard conversations about President Obama. I think that Avery was reaching for a portrait of the modern United States, the one that replaced the vast forests, but it just doesn’t work.

Strangely, although Avery takes an avowed scientific approach to the Passenger Pigeon, he does not think it is necessary to provide footnotes or a scientific bibliography. There is a chapter-by-chapter list of books and articles for “Further Reading”. He states, “If anyone has a good reason and a burning desire, to track down some references on Passenger Pigeons or other subjects mentioned in this book then please get in touch with me…” I find this not only odd but insulting. It is the essence of scientific and historical inquiry to know where information comes from and to have the option to read sources. I also find it strange that Avery nowhere acknowledges the work being done on the Passenger Pigeon by Joel Greenberg, who must have been researching A Feathered River Across the Sky at the same time he was doing his research and journey.

So, what book about the Passenger Pigeon should you read? For a comprehensive history, I highly recommend Greenberg’s A Feathered River Across the Sky. Greenberg’s graceful writing style and his knowledge of seemingly every story ever written about the pigeon makes this the preferable volume for those who want it all in as much detail as possible. For a more condensed but still engrossing account, enhanced by pages of images, I highly recommend The Passenger Pigeon by Errol Fuller. This is the more expensive title, but I think the quality of the book’s illustrations make it worth the purchase. And, for those interested in teasing out the mathematical puzzle of how many breeding Passenger Pigeons are needed to create a sustainable population, I refer you to A Message From Martha.

We live in a world where believe that anything is possible if you work hard enough. Or spend enough money. Or both. So, it is very strange to look at a painting of a large, long-winged, long-tailed pigeon with a reddish breast and think that it is gone. And there is nothing we can do about it. Yes, there is talk about bringing the pigeon back through the magic of science and the DNA of its closest relative, the Band-tailed Pigeon. We’ve all read Jurassic Park. We know that there is always a down side.

The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon didn’t happen for just one reason. It wasn’t just the mass killings in so many ways. Or the destruction of the forests, food source and breeding grounds. Or the development of technologies that transformed local killings into commerce. Or the absence of legal protection. Or the behavioral need of the pigeons themselves to survive in huge colonies. Nature can be complicated. The answer is ‘all of the above’ with a possibility of future complications. Let’s honor the Passenger Pigeon. Let’s read about its life with amazement and view the future within the prism of its death.

————————————-

The Passenger Pigeon

by Errol Fuller.

Princeton University Press, September 15, 2014.

Hardcover, 9.6 x 7.3 inches, 184 pages, $29.95.

ISBN-10: 0691162956, ISBN-13: 978-0691162959

A Message from Martha: The Extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and Its Relevance Today (Bloomsbury Nature Writing Series).

by Mark Avery.

Bloomsbury USA, August 2014.

Hardcover, 5-5/16 x 8-1/2 inches, 304 pages, $22.00.

ISBN-10: 147290625X, ISBN-13: 978-1472906250

Also available in Kindle format ($9.99) from Amazon and in eBook format from publisher.

A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction.

by Joel Greenberg.

Bloomsbury USA, 2014.

Hardcover, 304p. $26.00; paperback, $17.00.

ISBN-10: 1620405342; ISBN-13: 978-1620405345

Also available in Kindle format.

———————————–

…

Extinction is forever. A species, wiped off the earth, never to exist again. What a horror! What a disaster! What a wrong!

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

But, in the wider view of things, extinction is necessary. It is what drives evolution. Extinction is what befalls the species that fails to adapt, to survive, to thrive. Most species go extinct. That is just the hard, cold reality of nature, red in tooth and claw.

This is not to say that we should sit back and let the Holocene Extinction continue. No! We must fight to save every species we can, every ecosystem, every niche.

It is the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, once one of the most abundant species in the world. In order to raise our awareness, to remind us of what we have lost, and to inspire us to fight for Every. Single. Species. we are hosting Extinction Week here on 10,000 Birds from 7 September to 13 September. Come back, click through, read, learn. And get angry and take action.

…

Leave a Comment