So what’s so special about seeing the resident re-introduced Whooping Cranes in Florida? According to the ABA, they are not countable. And when you see them – as I have recently – they have massive transmitters and color bands on their legs. Moreover, the pair I saw was feeding from a livestock trough alongside a group of cattle. Hardly the elegant, natural picture deserving of some seriously stunning birds! But then I looked again at the color bands on the birds’ legs and wondered out loud, “there must be a story behind these majestic individuals”. Wouldn’t it be incredible, I thought, if I could trace back the ancestry of the two birds that I was looking at? So I called up a few friends with ties to the Whooping Crane non-migratory flock project in order to play a little bit of ancestry.com. And what I found made me take a step back in time and reflect upon how truly special these birds are.

One of the last remaining Whooping Cranes in the non-migratory Florida flock

One of the last remaining Whooping Cranes in the non-migratory Florida flock

Whooping Cranes occurred naturally in the eastern United States until the late 1940s, and there are records of Whooping Cranes in Florida until the 1930s. In 1938, they were reduced to only 18 birds in the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock and only 11 remaining in the non-migratory Louisiana flock. There was also one bird in captivity bringing the total number of birds to a paltry 30 in 1938. Just as World War two was drawing to a close the total number of cranes had dropped to an alarming 23 birds. By 1950, the Louisiana flock was gone. The Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock’s numbers hovered on the edge of collapse until the 1960s, never numbering more than 34 birds in total. By 1967, there were still only 43 Whooping Cranes in the wild.

The re-introduction of a non-migratory flock in Florida was designed to be an insurance policy should anything drastic happen to the migratory flock. Over a decade from 1993 to 2004, conservationists released 289 captive-raised Whooping Cranes into Osceola, Lake and Polk counties in Central Florida. Due to problems with survival, reproduction and predation from bobcats, a decision was made to stop releasing cranes into the non-migratory flock. Today only 19 members of this dwindling flock remain. However, studies of the surviving members of this flock still continue.

One of the only Whooping Cranes born in the wild in Central Florida, Number 1781

One of the only Whooping Cranes born in the wild in Central Florida, Number 1781

In late January of 2013 I spent some time with a pair of Whooping Cranes just off Canoe Creek Road in Osceola County, Florida. I reported the color-coding of the birds that I saw. The first bird had yellow above green color bands and the second bird had two blue color bands. Now who might these two individuals be? This needed some detective work on my part. I contacted Marty Folk from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and asked him if he had any clues. Turns out the two birds I saw were in fact both females. The yellow/green bird is identified as number 1781 in the Whooping Crane studbook and is remarkably only the fourth bird to have hatched successfully in the wild in Florida – on the 4th March 2004. The blue-blue bird is identified as number 1282 in the studbook, one of the oldest birds in the surviving flock, born at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center on the 2nd of June 1993 and relocated to central Florida on the 20th of April 1994.

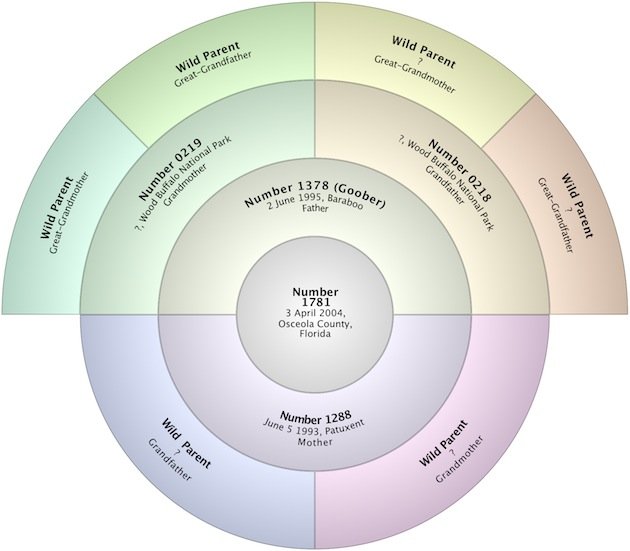

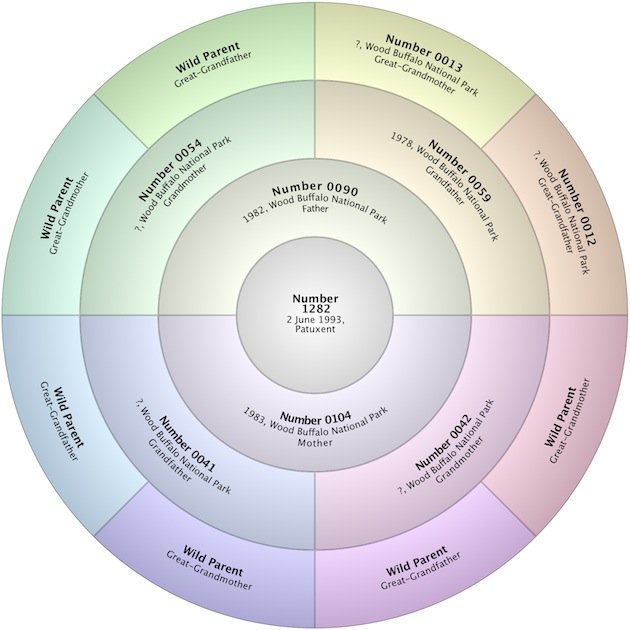

Now these birds had REALLY captured my interest so I was interested to find out their heritage. How far would I have to go back to find a wild ancestor? I have compiled the family trees of both birds below:

Ancestry Chart of 1781, born in the wild in Central Florida

Ancestry Chart of 1781, born in the wild in Central Florida

Ancestry Chart of 1282, one of the oldest surviving members of the central Florida flock

Ancestry Chart of 1282, one of the oldest surviving members of the central Florida flock

Its interesting to trace this genealogy for a number of reasons. Firstly, its relevant that 1781’s mother was relocated to Central Florida together with 1282 as two of the founding members of the non-migratory flock. 1282 and 1781’s mother were born within 3 days of each other at Patuxent. Could 1282 then be 1781’s maternal aunt? Secondly, its interesting to highlight that all of the ancestors of both birds come from Wood Buffalo National Park. Since there were only two birds in captivity when the Louisiana flock became extinct, its likely that the genetics of the non-migratory flock are lost forever.

But most importantly its vital to reflect on how close we came to losing an incredible species. If anyone is in doubt about the incredible feats achieved by this conservation success story please read about perhaps the most important Whooping Crane in the world, a resilient ancestor of much of the current population – Canus.

To learn more about Canus read here. And read more about the project here.

Lastly, thanks to all those from all the various agencies who have worked so tirelessly to give me – and other grateful birders like me – the chance to see these birds alive today.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUH2Yob-UO0

Thank you very much for the unique article, James. The “ancestry.com”-type research and results (including the graphics) were ~very~ interesting. And, the video made quite clear the large size difference between whoopers and sandhills. Thanks again.