In June, I visited North Dakota for the first time. Like any birder visiting a new place, I had a target species list I was hoping to seek out during the one day I had available between business commitments. And it was along a remote gravel road that damp, chilly morning that a flash of black and white whirred across my field of view, landing a short distance ahead and turning out to be my life Chestnut-collared Longspur (Calcarius ornatus). It was the first of many that day, and I was totally enamored of their gaudy plumage and beautiful, meadowlark-like songs, often delivered in a kind of hovering display flight above the prairie grasses where they live. That’s one of my photos above.

The experience was marvelous — but it also weighed heavily on me. That’s because I’d already seen the conclusions contained in a study that Audubon (my employer) was preparing to release, a study about birds and climate change.

That study, which came out Monday and can be explored in detail at Audubon.org/Climate, shows that Chestnut-collared Longspur could be gone by the end of the century if global warming continues at its current pace. It shows that of 588 species assessed, 314 species in the continental United States and Canada will lose half or more of their current ranges by 2080 if global warming continues at its current pace (which is approximately 8 degrees F of warming by the end of the century).

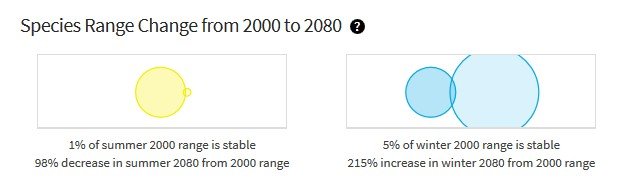

Many of those will lose so much range so quickly that extinction seems highly likely. Chestnut-collared Longspur is one of those. Here’s a diagram, available on the Audubon site, that compares its 2000 range with its anticipated 2080 range:

Only 1 percent of the bird’s breeding range remains stable between 2000 and 2080 if global warming continues on its current course. And this bird won’t be able to expand into new areas either — its expansion potential totals only 1 percent of its current range. Here’s how that looks on a map:

Scientists have long understood that climatic conditions, including temperature, precipitation, and seasonal changes, define species’ ability to exist in specific geographic locations. Those conditions shape entire ecological communities, which we birders tend to think of broadly as “habitat,” including the plants that birds need for shelter, nesting substrates, and food, and the other species that interact with birds in their environments, from predators to competitors to food sources like insects or fish.

Birds are finely tuned to the climatic conditions that support them. We have only to look at the distribution of birds like Colima Warbler in relictual forests high in what is now the Chihuahuan Desert to understand how closely tied birds are to specific environmental conditions. Are they adaptable and remarkably enduring and resourceful? Yes. But do they balance on a knife’s edge? In many cases, the answer is a clear and urgent yes.

The climatic changes set in motion by the Industrial Revolution are now proceeding at a pace far greater than many species and ecosystems can adapt to naturally. Scientists all over the world are sounding the alarm about ecological disruptions already in motion, and birders in North America are already seeing changes in the distribution of species, from the 61 percent of bird species wintering farther north to expanding ranges of birds like Mississippi Kite and Great-tailed Grackle.

The question Audubon scientists, led by Gary Langham, set out to answer was whether it was possible to anticipate which birds are most sensitive to global warming and how climatic changes will change their distributions. They had two world-class datasets on which to draw the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, and the North American Breeding Bird Survey. By combining decades of bird occurrence data with detailed climate data from leading climatologists, they created models that describe how climate conditions define where birds live today and have lived in the past. From there, it’s possible to project bird distributions under future climate scenarios, such as those published by leading international climatologists who make climate predictions based on global greenhouse gas emissions scenarios.

The results are, to me as a birder and conservationist, horrifying. I’ve discussed Chestnut-collared Longspur at some length already. The list of most-threatened birds continues; all of these birds could lose more than 99 percent of their current range in at least one season by 2080:

“[The Audubon study is] telling us that a whole additional suite of species will become highly threatened that aren’t the ones we’re worrying about now,” Stuart Butchart told National Geographic. Butchart is head of science at BirdLife International and chairs the IUCN Red List Technical Working Group.

You can read more about the study at The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, among others. Three papers coming out of the study are in peer review, and the research continues, with citizen science opportunities and additional data partnerships anticipated in the near future.

So during Extinction Week here at 10,000 Birds, here’s my pitch, from birder to birder: Get involved in the fight against global warming. Birds face a lot of threats, and we need to keep working on all of them. But this study shows how much is at stake for birds if global warming continues on its current trajectory, and it also offers a path forward — it helps identify stable areas on the landscape that will be refuges for key species or groups of species in a warmer world. The time to act is now. You can take action with Audubon or with any of the other terrific organizations working on bird conservation and the climate issue, but whatever you do, do something. When Corey’s, Nate’s, and Mike’s kids are running 10,000 Birds Extinction Week in 2050, I hope they’re still writing about the Dodo and not a whole new round of species destroyed by global warming.

…

Extinction is forever. A species, wiped off the earth, never to exist again. What a horror! What a disaster! What a wrong!

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

It is correct, of course, to think of extinction this way during the Holocene Extinction, which we are living through right now. After all, the extinctions have occurred, are occurring, and will occur because of us, people. We have so altered the earth – pumping pollution, moving species around, destroying ecosystems – that many species, dependent upon ecological niches or simply unprepared for an onslaught of unfamiliar organisms with which they did not evolve, have no chance. It is depressing and angering and just wrong.

But, in the wider view of things, extinction is necessary. It is what drives evolution. Extinction is what befalls the species that fails to adapt, to survive, to thrive. Most species go extinct. That is just the hard, cold reality of nature, red in tooth and claw.

This is not to say that we should sit back and let the Holocene Extinction continue. No! We must fight to save every species we can, every ecosystem, every niche.

It is the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon, once one of the most abundant species in the world. In order to raise our awareness, to remind us of what we have lost, and to inspire us to fight for Every. Single. Species. we are hosting Extinction Week here on 10,000 Birds from 7 September to 13 September. Come back, click through, read, learn. And get angry and take action.

…

Excellent post and thanks for giving readers an idea of how dire the scenario is likely to be. In Costa Rica, just as was predicted, it has been getting warmer and drier for a few years now. The vegetation at various humid forest sites looks stressed, a lot of bird species just don’t seem to be as common as in the past, and really don’t think think those observations are explained by observer bias or chance. I’m afraid that there’s a pretty good chance that some species will be lost in Costa Rica, maybe some of the highland endemics. I hear your call to action, we all need it and not just because we like watching birds. If something isn’t done to seriously slow down global warming, a hell of a lot of people are going to get a really rough lesson on their obvious connection to the natural world.

Can I play devil’s advocate for a second? Here is the entry for the Bald Eagle. “The national symbol of the United States is projected to have only 26 percent of its current summer range remaining by 2080, according to Audubon’s climate model. However, it could potentially recover 73 percent of summer range in new areas opened up by a shifting climate. Its success isn’t guaranteed in the new areas—the majestic raptor will still have to find suitable food and nesting habitat.”

This is “on the brink”? Hyperbole, much? Yes, a lot of species with restricted ranges and finiky habitat requirements are in a lot of trouble. A wide ranging and adaptable tramp like the Bald Eagle? If it can’t survive these kinds of shifts I wouldn’t bet on us being able to either.