To start, some general information on the difference between pigeons and doves: there is none, at least not in a scientific sense. Both terms describe the same family of birds, and there is no clear rule as to why a specific species within the family is called a dove or a pigeon.

That said, there are some “soft” rules and also some differences in perception:

- Smaller members of the family are more likely to be called doves, larger ones pigeons

- Some people think of white birds as doves and grey ones as pigeons – however, as the photos below show, this isn’t very helpful

- Doves are more likely to be seen as peace symbols, pigeons are more likely to be seen as flying rats

- The word pigeon has its roots in the French language while the word dove is of Nordic origin

Now that we are clear on this, let’s look at some of the doves (and pigeons) of Halmahera and Sulawesi, starting with the Grey-headed Fruit Dove.

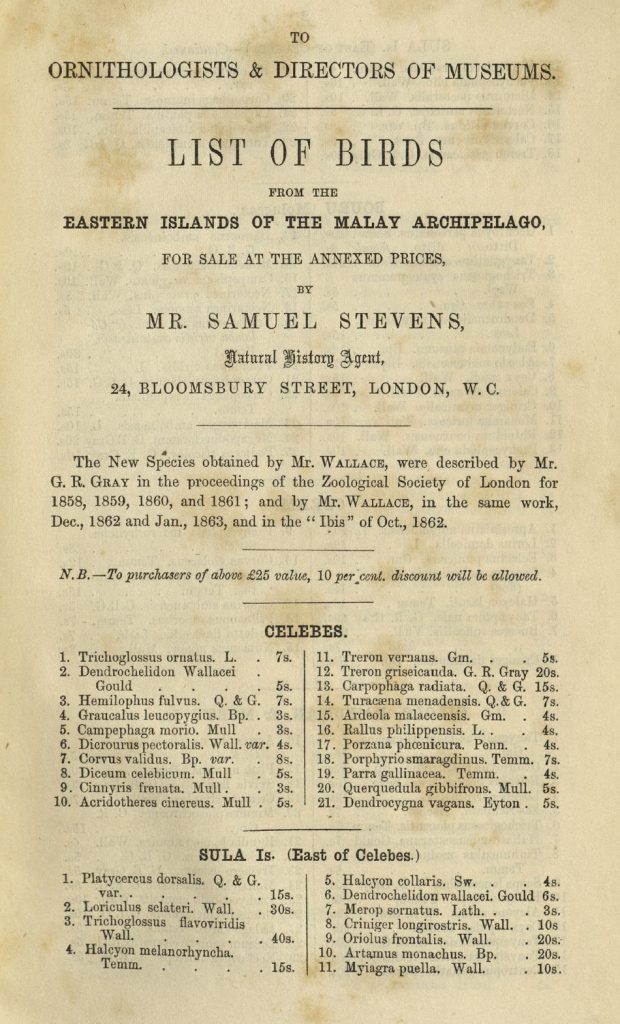

If you had a time machine and some spare time after having killed Hitler, you could enter the year 1863 and take a look at Vol. 5 of The Ibis of that year. This issue contained four loose inserts advertising specimens for sale by the natural history dealer Samuel Stevens.

Illustration taken from the article “A price list of birds collected by Alfred Russel Wallace inserted in The Ibis of 1863” by Kees Rookmaaker & John van Wyhe, Bull. B.O.C. 2018 138(4).

These inserts showed a list of bird specimens collected by Alfred Russel Wallace in the Indonesian Archipelago. The prices charged ranged from 3 to 240 shillings each, or an average of 11 shillings per specimen (with a discount of 10% for purchases above 25 GBP).

If you had remembered to bring enough shillings with you on your time machine, you could now buy a specimen of the Grey-headed Fruit Dove – as collected by Mr. Wallace – for 10 shillings.

While that sounds cheap, an agricultural or general factory workers typically earned about 10 to 15 shillings per week, so the estimate provided by ChatGPT “10 shillings from 1863 would be roughly equivalent to $80 to $90 USD today” seems a bit on the low side.

A bit of background: Wallace travelled through the Malay Archipelago between 1854 and 1862. His main objective of all journeys was to obtain specimens of natural history, both for his private collection and for museums and amateurs. He had an arrangement with natural history dealer Samuel Stevens. Wallace sent all his materials to Stevens, who then stored those Wallace wanted to keep and tried to sell the others.

Wallace probably did not bother to capture any Zebra Doves – they are just too common. Not worth the effort if you can only charge one shilling for it.

However, the next 5 dove species shown in this post were all on Wallace’s “For sale” list. I have indicated the asking price for each specimen in brackets behind the species name.

Black-naped Fruit Dove (8 shillings): this species is an obligatory fruit eater – it only eats fruit. One of the consequences may be that its metabolic rate is substantially lower than that of birds without these dietary restrictions (source).

Another, probably related difference from other doves is the higher water content and lower fat content of its meat – 74% water and 4% fat compared to 53% water and 30% fat for the Common Emerald Dove (source).

The Black-naped Fruit Dove can be found in a surprisingly large number of zoos all over the world, including Tulsa, Barcelona, Columbus, Salt Lake City, Cleveland, and Milwaukee – more than 50 zoos altogether (see this list).

At only 7 and 8 shillings (Wallace offered two specimens in his list), the White-faced Cuckoo-dove apparently was not regarded as a very exciting bird despite being a Wallacean endemic with a limited distribution on Sulawesi and its satellites.

The genus name Turacoena (full scientific name is Turacoena manadensis) is interesting as it combines the words for Turaco (which indeed this species resembles a bit) and “oinas”, Greek for pigeon.

The Blue-capped Fruit Dove (8 shillings, if you wanted to buy it from Wallace in 1863) is a North Moluccan endemic described by Cornell as a “handsome, diminutive” species.

It is not very common and probably in decline due to habitat loss, which explains its listing as Near Threatened by BirdLife International.

Presumably, the “monk” (monacha) in the scientific name Ptilinopus monacha refers to the cap of the bird.

The Slender-billed Cuckoo-dove was priced a bit higher at 10 shillings. The species found on Halmahera, where these photos were taken, is now called Sultan’s Cuckoo-dove.

The scientific name Macropygia doreya does not refer to somebody’s girlfriend named Dorey but rather to Dorey meaning New Guinea – which is still somewhat misleading as the center of this species’ distribution seems to be a bit further west than New Guinea.

I asked ChatGPT about the “Sultan’s” in the species’ name. ChatGPT told me that “The name ‘Sultan’s Cuckoo-Dove’ (Macropygia doreya) is somewhat misleading because it does not actually refer to a historical sultan or a specific person. Instead, the name ‘Sultan’ likely reflects the bird’s perceived regal appearance or distinguished presence”

I was not quite sure about this reply, so I asked back: “But if that explanation is correct, shouldn’t the bird be called Sultan Cuckoo-Dove, as in ‘Sultan Tit’?” ChatGPT agreed to some extent, I guess: “You’re correct in noting the difference between ‘Sultan’s Cuckoo-Dove’ and names like ‘Sultan Tit.’ The possessive form ‘Sultan’s’ versus the non-possessive ‘Sultan’ in bird names can indeed be confusing. The naming conventions in ornithology don’t always follow a strict pattern, and this can lead to such discrepancies.”

Back to Mr. Wallace and his offerings. The Great Cuckoo-dove sold for 20 shillings – the only dove selling above the average of his specimens, though still far lower than the 240 shillings he asked for the most expensive bird in the list, the Twelve-wired Bird-of-paradise.

The scientific name Reinwardtoena reinwardti is a bit embarrassing for Prof. Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt (1773-1854), a Dutch naturalist and collector in the East Indies – using his name once would surely have been enough. Modesty apparently was not among his core character traits.

Also, why name a bird after a botanist? The name was given to the species by Temminck – I wonder whether, in return, there are some plants named after him … I might be too cynical but I am usually right …

For those who could not afford 20 shillings for this species, a Pied Imperial Pigeon was available for 15 shillings. A bargain.

The last few doves shown in this post were not on Wallace’s list, so I cannot tell you their price in 1863.

But the Ruddy Cuckoo-dove still has a decent connection to the main storyline of this post. Its scientific name is Macropygia emiliana. And the emiliana refers to François Charles Émile Fauqueux-Parzudaki (1829-1899), a French natural history dealer with a strong focus on birds and thus a competitor of the dealer used by Wallace, Samuel Stevens (source).

François Charles Émile Fauqueux-Parzudaki was in this business until approximately 1867, so would have been active when the price list shown at the beginning of this post was published. Strangely, in 1874 he took over the management of a shoe factory, something that most modern birders and ornithologists might struggle with.

The Green Imperial Pigeon is listed as Near Threatened, which is a bit surprising given that the Cornell entry states that the species “remains a reasonably common and easily encountered species across large parts of its range”.

The subspecies shown here – seen on Sulawesi – should be the subspecies Ducula aenea paulina. It is named after Antoinette Pauline Jacqueline Knip née Ryfer Courcelles (1781-1851), a French bird artist. You can see one of her works here.

Cornell makes the species sound like a regular participant in air shows: “Male performs spectacular display-flight, commencing in normal flight, then suddenly beats wings vigorously and shoots vertically upwards over c. 2 m, before stalling momentarily with wings flexed and neck outstretched, as if about to tip over backwards, finally turning sharply and diving down, then resuming normal flight, or rises from trees to perform similar flight”.

Unfortunately, these performances are strictly done for females of the species, not for birders like me, even if they come from foreign countries.

Finally, the Cinnamon-bellied Imperial Pigeon is basically a Halmahera endemic.

It is one of about 36 species in the genus Ducula, the Imperial Pigeons.

While Wikipedia claims that Ducula is derived from the Latin dux genitive ducis meaning “leader”, Cornell states that Dukul is the Nepalese name for the imperial pigeons. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird names, apparently not wanting to take sides, offers both explanations.

Nicely illustrating the pointlessness of some Google research, I also found that the Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo, Norway has a specimen of the species.

Charles Lucien Bonaparte came up with the genus Reinwardtoena so the dear botany professor is innocent of the crime of self-promotion. Coenraad Jacob Temminck did indeed name the species, also after the same botanist. As Temminck has had species named after him across the natural realms I would like to believe he is innocent of the foul play Kai is insinuating. Is Dr Pflug upset because the work by Hahn & Pflug on cloudinids (1985) did not deliver a reciprocal species name?

but the photographs are gorgeous so all is forgiven

Coming from a lifelong pigeon hater: these Sulawesi and Halmahera pigeons are actually… kinda amazing. Colorful, cool, and nothing like the city ones!

While I would not mind at all to have a species named after me (“Pflug’s Ground Twit”), I know it would be a short-lived triumph as in the current climate of wokeness, my past as a slave trader would soon catch up with me.

Some stunners there Kai.