Take a quick look at the breeding distribution of European birds and you will see that there are a surprising number of species that are restricted to the Balkans. (The Balkans, by the way, is a loose term for Europe’s south-eastern peninsula, covering the countries of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Bulgaria and Greece.) It is these Balkan specials that are the target species for most birdwatchers visiting the area from western Europe.

The Balkan specials are a remarkably diverse lot. The largest of them is the Dalmatian Pelican, which with a wing span of around 10ft and a weight of up to 26lb is a serious contender for one the world’s biggest flying birds. Go to the right location and you can’t miss it, which is more than you can say for the Olive-tree Warbler. The latter is big (the biggest of all the Hippolais warblers), buy shy. As the Collins Bird Guide notes, it “keeps well hidden”. You will hear more than you see, and you can’t generally guarantee to hear one, either.

Because Olive-tree Warblers are such a challenge to find, and, to be honest, not that exciting to look at when you do eventually see one, they don’t feature here in my Balkan Top Ten. Instead I’ve selected my favourite 10 species I expect to find when I visit Greece, only some of which are restricted to the Balkans. These are all birds I expect (or hope) to see on a visit here.

No 1

The Dalmatian Pelican has to take the No 1 spot, as it’s so big and spectacular. It is slightly larger than the White Pelican, in whose company it can often be found. Compared to the clean-cut White, it’s not such a smart bird, its plumage tinged with grey, while the curly feathers on its head look as if it needs a visit to the hairdresser. It’s in late winter and early spring when these pelicans look their best, as the huge bill pouch develops an intense shade of orange-red, indicating that the bird is in peak breeding condition, but this soon fades back to a dull yellow.

The classic sites for seeing these pelicans are Lakes Prespa (with the world’s largest colony), Amvrakikos and Kerkini, but they do wander, and often turn up at other wetlands, and even in harbours close to Thessaloniki.

No 2

OK, you can find White Storks in many European countries, but they are one of the most characteristic birds of Lake Kerkini: the village of Kerkini (from which the lake takes its name) has over 40 nesting pairs. Most arrive in March, but by mid September they have migrated back south to their wintering grounds in Africa.

White Storks build huge nests which get bigger every year as the owners add more sticks and material. In Greece these impressive nests often host colonies of Spanish Sparrows that nest in holes in the structure. Such a nest site has its risks for the smaller occupants. In May this year I watched a sitting Stork catch and eat one of her tenants. Such an unfriendly act created a lot of excitement among the sparrows, many of which came out to sit on the nearby wires to discuss the event. After a while peace was restored, and the sparrows returned to their nesting chambers,

No 3

Forty years ago the Greater Flamingoes was a rarity in Greece, with fewer than 30 records. Today it’s become a familiar wintering bird, with flocks of thousands to be seen at favoured localities. I know it well from the salt pans at Angelochori, just a few miles to the west of Thessaloniki’s airport. Here flocks can be seen in most months of the year. (This is a fine site for other birds, with a variety of waterbirds and waders invariably to be found here, including such as species as Black-necked Grebe, Avocet and Slender-billed Gull).

In recent years Greater Flamingoes have spread eastwards and now breed regularly in Italy and Turkey, while in 2020 the first successful breeding was recorded in Greece, at the wetland of Agios Mamas in Chalkidiki. Greater Flamingoes are strikingly handsome birds and it’s encouraging to find them doing so well in Greece today.

No 4

Spoonbills aren’t a Balkan special, as they even nest now in my home county of Suffolk, but there’s nowhere better to see them at close range than on their breeding grounds at Lake Kerkini. Here the recent loss of the flooded forest means that the majority of birds now nest away from the lake, commuting to it to feed.

Numbers decline in the winter, but birds can be seen in Greece all year round. The young birds can be easily identified by their black-tipped primary feathers.

No 5

As the name suggests, the Levant Sparrowhawk is a Levantine special. Very similar in both appearance and behaviour to the closely related Shikra, it’s a bird that favours open lowlands, and is often to be found around villages. It’s a late-returning migrant, not generally appearing back on its breeding grounds until early May.

The shrill call is loud and far carrying, and unlike that of any other European raptor. When I heard my first one, on a visit to Kerkini in 2008, I wasn’t sure what it was, and had to find the bird to establish its identity.

No 6

Arguably the most exotic-looking of any European bird, the Bee-eater is always a delight to see and hear. It’s a widespread breeding bird throughout much of the Balkans, arriving back in early May and staying until late August. This is a bird that was once widely persecuted, as its liking for bees made it the enemy of the bee keeper, giving an excuse for it to be shot.

Incidentally, on a good day’s birding in northern Greece it’s possible to see all five of Europe’s most brightly coloured birds: Bee-eater, Roller, Hoopoe, Golden Oriole and Kingfisher. Though it’s possible to see the same Big Five in a number of other Mediterranean countries, Greece is the only country where I have managed it regularly.

No 7

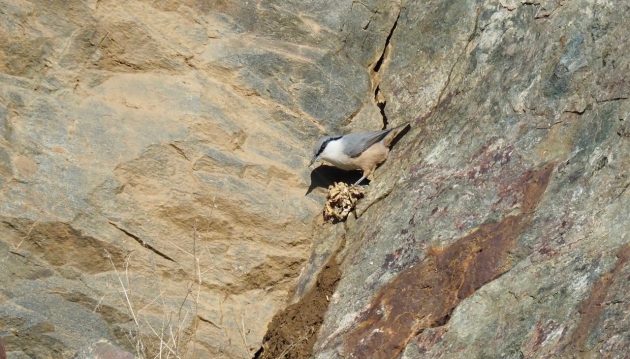

There are 10 species of woodpeckers in the Balkans. The only one I haven’t seen here is the Three-toed, which is restricted to the Rhodope Mountains on the Greek/Bulgarian border. The White-backed is also a real challenge to find – the bird shown here I photographed close to the town of Sidirokastro, a few miles south of the border with Bulgaria. Records of White-backed Woodpeckers in Greece are few, so the status of this woodpecker is something of a mystery.

The race of the White-backed Woodpecker here is lilfordi: it was once known as Lilford’s Woodpecker. Lord Lilford was a 19th-century English bird enthusiast and collector: he shot a mystery woodpecker in Greece in 1857 that was named Picus lilfordi, but it was later reclassified as a race of the much more widespread White-backed Woodpecker.

No 8

Rock Nuthatch. Officially known as Western Rock Nuthatch to differentiate it from the Eastern bird (that can be found in Georgia), this noisy and active bird is widespread in Greece in suitable habitat, but not always easy to find. I saw my first individuals at Delphi many years ago. They are widespread in quarries and on suitable rocky hillsides in northern Greece. Listen for their distinctive loud whistles.

Earlier this year I heard one calling in a large disused quarry in northern Greece where I had seen these birds before, but despite my best efforts I failed to see it. Frustrating, but they are small birds that favour big landscapes.

No 9

Four species of shrikes nest in Greece – Lesser Grey, Red-backed, Woodchat and Masked – but it’s the latter that’s the Balkan special. The smallest and most delicate of the European shrikes, the Masked is not as easy to find as the other species, as you rarely see one perched on roadside wires or sitting conspicuously on the tops of bushes.

Masked shrikes prefer an open wooded habitat, so have their own ecological niche, not competing with their larger cousins. Numbers have been increasing in recent years, so this is a bird that you should see if you put the effort in.

No 10

Wandering Black-headed Buntings have been found as far west as Britain, and they do breed in southern Italy, but this is predominately a Balkan (and Turkish) bird, migrating to India for the winter. They return in early May, when the cock’s distinctive and oft-repeated song is a characteristic sound of the Greek countryside.

When singing they usually perch conspicuously at the top of a large bush or small tree where they are easy to see. In contrast, the much drabber females can be difficult to find. The cock is a very handsome bird that I never tire of seeing, its song one of the most characteristic sounds of northern Greece in May.

Makes me want to go to Greece immediately – though I guess future lists will give me similar thoughts, so the choice will be hard …

I will join you, Kai!

That story about the stork and sparrow was fascinating!

Interesting to learn that Serbia is not in the Balkans. And you may sadden the Greek tourism board, they deliberately avoided the word Balkans in any brochure they ever produced.

PS. Croatia (or its larger part) is also in the Balkans. Basically, the area south of the Sava and the Danube rivers.

I need to get to some of your mainland sites, David. Great overview but, personally, I’d elevate the shrikes up the list but that’s just me! Do you have good lesser grey sites?