As a child of the eighties, I experienced a number of elegies for Whooping Cranes. Commentators seemed to take their extinction as inevitable, although in fact their numbers had begun a slow climb from their historical nadir and would break the 100-individual mark in 1986. It was more that this was a gloomy era. Nuclear dread, viral plague, and a general sense that doom was upon us all probably had a lot to do with our vision of the Whooping Crane‘s prospects.

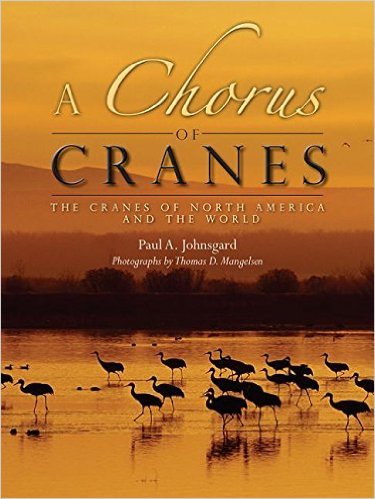

While I was becoming a dour and mistrustful child perfectly primed for the advent of Trent Reznor, though, Dr. Paul A. Johnsgard was actually doing something about it. To be fair, he was slightly better positioned to do so, being a professor of biological sciences with the University of Nebraska. His overall expertise on the biological diversity of his adopted state led him inevitably to an appreciation not only of the Whooping Crane, but also the more common, smaller, but no less fascinating Sandhill Crane. As the subtitle implies, this appreciation drives the bulk of A Chorus of Cranes: The Cranes of North America and the World.

Johnsgard blends a scientific and a poetic regard for these birds and the habitats they depend on in a way that’s reminiscent of Aldo Leopold — a higher compliment than which I cannot think to bestow. His prose is elegant and vivid without shading to purple or neglecting to communicate actual facts. His description of the Platte River on page 39, in the midst of the chapter on the Sandhill Crane, stands as one of the best single paragraphs of nature writing I have recently read, bringing across both the critical hydrological factors and the sweeping power of the Rocky Mountain-plains interface in a mere four sentences. The photographs by Thomas Mangelsen are in the same spirit, while Johnsgard’s numerous line drawings of various species and behaviors add an old-fashioned charm as well as valuable visual information to the pages.

While the book as whole is both pleasurable and educational, I found the section on Sandhill Cranes to be the most engaging. This species, always more common than the Whooping Crane, has been relatively neglected in the literature, and Johnsgard does an admirable job of tracing its scientific history, the panorama of various races and regional variations, its life cycle, and its relationship to the landscapes where it lives. The Whooping Crane gets a similar treatment, as well as a clear-eyed and sober assessment of the conservation efforts for this species; not another premature elegy, but a reasonable reminder that it is that it is the habitat, and not merely the species, which we must preserve. The rest of the cranes of the world receive only brief species accounts — while I would have loved to see more on all these birds, a single volume could hardly have contained them all and perhaps it is better for them to be more extensively treated by authors who know and love their worlds as Johnsgard knows and loves Nebraska.

My major complaint about this book, unfortunately, relates to the physical nature of the volume. While economic constraints on print stock and bindings are real and valid, the sad truth is that a paperback book of this size tends to flop about, which can make reading a bit of a challenge. A sturdy desk or table is this book’s natural habitat, especially if your wrists are unsteady after a long day of binocular-hoisting.

That issue aside, this is a book well worth seeking out.

Carrie – have you read Matthiessen’s The Birds of Heaven on cranes? One of the great pieces of natural history writing for me and, if you’ve not yet read, it will give you the in depth treatments of the rest of the world you mentioned.

It’s funny Tai, I thought of that book too. But honestly I found it florid and almost unreadable. I guess I prefer my natural history writing a bit more down to Earth.