The “clickbait” title for this post could well have been “The gays are making our bears queer” but no, this is a book review, not a cable news show. It is however, a review with a high potential for offense, hurt feelings and other emotional drama that normally drives us all into fields and woods to watch birds. It’s not too late, you can still go…

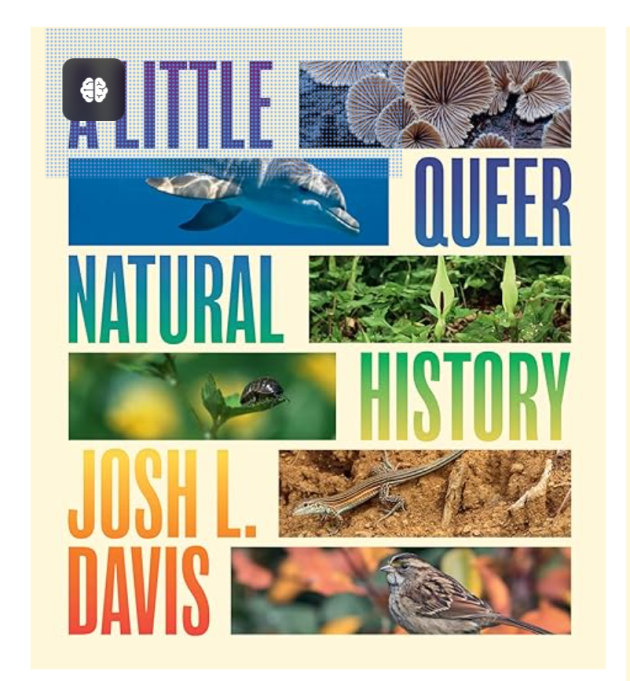

Reviewing “A Little Queer Natural History” by Josh Davis is of course a minefield for the politically incorrect middle-aged white male that I am. I do consider myself reasonably qualified regardless (of course). More importantly, everyone else on the 10000birds.com beat was busy birding. Let’s navigate past the explosive charges and hope for wisdom and forgiveness (in case wisdom isn’t enough). For this post I did a lot of heavy editing: I removed potentially offensive remarks and gratefully added my cousin Veronica Baas’ pictures. Maybe I have been over-sensitive (doubtful). Surely there are more important issues in the world: war, pestilence, famine, a narrowly avoided octogenarian presidential race between incompetence and incontinence?

How does a complete novice to the field of book reviews and an absolute minion compared to our beat reviewer Donna do a book review? You wing it! I’d like to base this review on three criteria: [1] does it stick? [2] is it truthful? and [3] is it fun to read? To stick with the book’s theme of doing things differently than one would expect – let’s cover these criteria in reverse order.

Is it fun to read?

This book is not a page turner, which is not surprising as I don’t think it was meant to be read in one go. The book is a series of monographs on behaviours/traits/reproductive systems across all taxonomic kingdoms. Pretty pictures, fun facts, very well researched. However, for a book with a citation of the memorable ‘A Note on the Apparent Lowering of Moral Standards in the Lepidoptera’ I would have expected much, much more fun. After all, lowering moral standards is the recipe for good parties. This is a book about sex – it features those randy Bonobos, gay Cockchafers (nomen est omen), and the humble penis gets 29 mentions (yes, I counted) – but the word fun only appears in fungi. Pronunciation fun guy, but still. It’s like sex education at school – the teacher stutteringly describing an activity that did not sound as the fun we all knew it was…

The author starts with the statement that the book is not meant to justify queer behaviours – animal or otherwise. Mr Davis rightly states that these behaviours need no justification – there is no morality in nature. However, in the following 120 or so pages one human rights violation after another is being called out based on the observed animal (or plant or fungi) traits and behaviours. Reinforcement of bias against homosexual behaviour, medicalisation of queerness, eugenics – it all gets more than a passing mention. I became overwhelmed once I reached the chapter on sheep. There happens to be a lot of study into farm animal homosexuality because studs need to be ladies’ men, anything else is bad news for the farmer (food in, nothing out). Warning those doing the research of the political and societal consequences is a bit of an exaggeration. Gay rams are slaughtered because a ram has only one purpose on the farm. By the way, being male (gay or straight) is a death sentence for any farm animal unless the individual is a good breeder. If you don’t like that idea, become a vegetarian.

The stories are good, and the examples of behaviour are riveting so I feel the argument could have remained implicit and be more effective through the storytelling. Preaching isn’t teaching.

Is it truthful?

Or in my interpretation, is it scientific? This is where I struggled most. The use of “appears to be” and “seems” is too frequent, but I felt there were sufficient caveats too, so the balance wasn’t off kilter. What I really could not get over was the mixing of science (the rational approach to problems through a time-tested method that has brought tremendous value to humankind) and scientists (people like you and me, with prejudices, poor bowel movement and nose hair). The morality gets in the way. When the author concludes that complex mating systems and sexual organizations show that generalizations can be tricky to apply to biology, he is right. Then, in the same sentence, he states that language is imperfect when talking about nature’s vast sexual diversity and range of combinations. This is the conclusion of an item about… a tree! The author draws the correct conclusion that science is influenced and informed by people, and people are …packed full of explicit and implicit biases, which have resulted in centuries of obfuscation, disinformation and coverups… Directly followed by the statement that the …science around queer behaviours in the natural world has become more objective in the last few decades, it is still often far too easy to slip back into old prejudices… Again, science is always objective – the scientists are not. I know the author works at the Natural History Museum in London and I do not, so I am not in the position to lecture him on science, nor do I want to but it just jumped out at me.

In the introduction, the author expresses his hope that the book and the examples it highlights flip the question of “why does homosexuality exist in nature when it appears to go against evolution?” on its head. I failed to see the flip. Nevertheless, the answer to the question is that nature does not select against homosexuality. Nor should we.

Does it stick?

Will I remember this book in years to come or will it turn out to be ephemeral? Disagreement can be a powerful stimulus for thought and consideration. I disagreed with almost every statement about science versus scientists as mentioned, I don’t buy into a lot of the hypotheses and even the philosophy behind the book feels wrong. Why? I do not believe queer animals, plants, algae, fungi can teach us tolerance, understanding and love for our fellow humans – that should come from ourselves, Homo sapiens.

The book excels in showing the reader the complexity of nature, of reproductive systems, all the different ways genes can be packed into chromosomes, how the environment or other living beings can influence what crawls out of an egg. The book reminded me again how weird plants are, how long they live. There are Neotrogla barklice that eat batshit and never see the light of day – their reproductive organs have taken on the second purpose of nutrient transfer. White-throated Sparrows have 4 “genders” (male tan-crown, female tan-crown, female white-crown, male white-crown) and male white-crowns only want female tan-crowns and vice versa. I did not know any of this, and those facts alone make me happy that I have read this book.

What on earth does your race have to do with anything?