Louisiana is a magical place to bird. I know because I was there in 2015 with friends from New Jersey Audubon and I was amazed by the close-up views of Mississippi Kites and King Rails, the sounds of Bachman’s Sparrows and ___, and most incredibly, a coastal fallout of migrant songbirds at Peveto Woods and Willow Island that included dozens of Philadelphia Vireos, Bay-breasted Warblers, Indigo Buntings, and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. At the same time I was ogling Scissor-tailed Flycatchers and Upland Sandpipers, Marybeth Lima was also birding Louisiana. The year is not covered in any depth in her book Adventures of a Louisiana Birder: One Year, Two Wings, Three Hundred Species, but thanks to eBird I know that she and her wife, Lynn Hathaway, were birding Peveto Woods ten days before the fallout, and probably in many of the other southwest Louisiana hotspots on our itinerary, and I can’t help wondering if we passed them on a path or road. (Please note, I was not engaging in eBird stalking, I came across Lynn Hathaway’s checklist while trying to reconstruct my own Peveto Woods checklist, which I was shocked to find out was never completed.)

This is the charm of Lima’s book. It is the story of a birder who I think is a lot like many birders I know, only maybe a little more intense, a little more thoughtfully. Marybeth learns as she birds, embraces listing goals as a means of engaging with community, unabashedly enjoys a little competition, struggles to balance her absolute joy in birding with unexpected, life-and-death family obligations. The book focuses on two listing events: her 2012 Louisiana Big Year and her 2016 Louisiana 300 Year. The 300 Year is not a Big Year, she writes, but rather a year of birding with the goal of 300 birds for the state; she ends up surpassing that goal, but I’m not going to give more details because that would be a bit of a spoiler.

The book is structured in a way that made much more sense after I read it than as I was reading it. Chapter One is all about Marybeth’s 2012 Big Year, an adventure she shares with Lynn, a fishing enthusiast who is probably the most supportive big year/300 year birding partner in the history of listing. I was initially puzzled by this chapter, there seemed to be a lot packed into it, from Marybeth’s childhood nature memories in New England to casual birding (birding without listing) in Baton Rouge, to attending the Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival in 2011 with her birding mother, to the big year itself, which turned out to be a year-long course in ‘how to bird Louisiana.’ What was left to write about?

Chapter Two is a potpourri of stories about nemesis birds, birding by ear, birding for science, under the rubric of birding ‘for the love of it.’ “Is this going to be a collection of essays?” I wondered. But, in Chapter Three the book takes on more shape. A little more than halfway through 2014, a year Marybeth had decided would be devoted to finishing in the top fifty eBirders in Louisiana AND Alabama, there is a terrible accident and time must be put aside for Lynn’s healing and recovery. The theme of the frailty of life and the importance of placing people before birding had been foreshadowed in an earlier chapter when Marybeth and Lynn stop birding to help rescue a man being pulled out to sea at Grande Isle (their binoculars enable rescuers to locate the man). It takes on more meaning in succeeding chapters as Marybeth and Lynn unexpectedly must balance their 300 Louisiana Bird Year with the care of Lynn’s increasingly frail mother (add a major flood into the year too). Any birder struggling with birding-work-life balance will understand the title of Chapter Four–“The Year of the Day Trip.” And the mixed feelings Marybeth describes when she reaches that magical 300 mark.

Don’t get me wrong, this is not a depressing or sentimental book, far from it. It is filled with birding adventures that could only happen in Louisiana and birding adventures universal with a Louisiana flair. Marybeth and Lynn participate in the Yellow Rails and Rice Festival, walk a line down an airfield in northwest Louisiana to flush Smith’s Longspurs, kayak to Dawson Creek from their Baton Rouge backyard when the great flood hits their home (it gets scarier later). They go on a lucky pelagic down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico (which Marybeth considers “a form of cheating,” a characterization I strongly disagree with); are the recipients of an unlucky speeding ticket on the way to a birding rendezvous (given by a cop who nicely suggests they talk to the city district attorney to get it waived); push themselves for the pure joy of birding and listing to surpass the magic 300 number.

There are the state’s unique habitats–swamp forests, coastal prairies, oak cheniers, wetlands of fresh water and salt water. This is one area that I think doesn’t get the attention it deserves. I would have preferred a little more about Louisiana’s landscapes and biodiversity and less of the tracing of routes by number and road name; clearly this is not the author’s forte. People are, and we get to know a lot of Louisiana’s birders, from the friends who welcome her to a birding camp on Grand Isle to the homeowners who open their yards and bird rarities to strangers to the birding ornithologists of LSU–Donna Dittman, Steve Cardiff, and J. Van Remsen, to the Louisiana birding community whose members respond immediately and enthusiastically to Marybeth’s requests for information and access. One likes to think this is true of all birding communities and it probably is, but Louisiana’s birders seem to be particularly sharing of ‘secret places’ and backyards. Marybeth Lima’s ‘real life’ work is academic, she is a professor of biological and agricultural engineering as Louisiana State University with research interests in community-based design and service-learning in engineering. Her previous book is Building Playgrounds, Engaging Communities: Creating Safe and Happy Places for Children (2013), about a 15-year project developing partnerships between LSU students and the Baton Rouge public school community. So, it’s no surprise that the personalities, work, and contributions of the birders of Louisiana take up

And there are the birds. With two of North America’s major flyways, Mississippi and Central, overhead, and with almost 400 miles of coastline Louisiana is one of those states where you can see Eastern and Western birds and a hell of a lot of shorebirds and waterfowl. (The checklist of the Louisiana Ornithological Society was at 485 as of August 2020.) Marybeth and Lynn chase birds familiar and unfamiliar to me, a Northeastern birder, and I’m sure it will be the same for any reader in North America. Smith’s Longspurs, Vermillion Flycatchers, Burrowing Owls, Long-billed Curlews, Virginia Rails, Black Terns, Crested Caracaras–there’s a bird here for every taste.

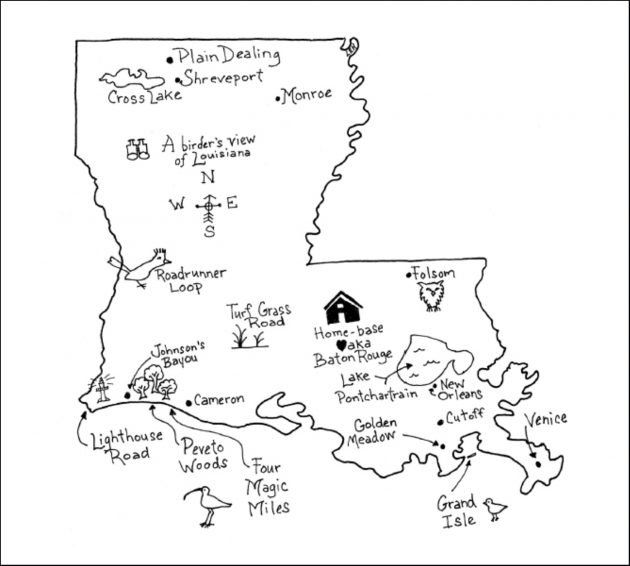

Map by Lynn Hathaway. Copyright @2019 by Louisiana State University Press

As the text makes clear, Marybeth doesn’t take photographs on her birding adventures. Lynn does, but there are no photographs in this book. There are black-and-white drawings by Aaron Hargrove illustrating some of the birds Marybeth writes about– a Red-shouldered Hawk on a wire eating a garter snake, a Grasshopper Sparrow in a chainlink fence, a staring Burrowing Owl inside a drainage pipe, and a few more. These are story illustrations, a little clunky, a little humorous, a little unique. There are also appendixes: a sample of Marybeth’s field notes with an explanation of her individual practice (I really like this, a nice counterpart to all the mentions of eBird throughout the book); a listing of the birds found on the 2016 300 year; Notes explaining certain birding and Louisianan terms, citing relevant books, articles, and websites; and an excellent index.

There are many Big Year books about big Big Years–the United States, Great Britain, the world–but not many about books about state Big Years (listen to the April 2020 ABA Podcast with myself, Nate Swick and Frank Izaguirre for more on Big Year narratives). And, while I understand that entering the Louisiana 300 Club was Marybeth and Lynn’s goal, this really does read like a book about two Big Years, two very different big years. Like the best Big Year books, Adventures of a Louisiana Birder has a deeply personal layer to the bird quest, in this case experiences of danger and recovery, frailty and loss, mourning and hope. Marybeth Lima tells her birding and personal stories in straightforward, honest language that never skimps on detail (sometimes a bit too much detail) but never overflows on emotion. She started out with the goal of writing about “birds, birders, and Louisiana” she writes in the Preface, and as she wrote she added two more goals: illustrating how birds and birding help get you through difficult experiences, and “to share the story of the end of a person’s life in the hopes that the experiences that come with it might be helpful to others” (p. x). I think this is unique in the Big Year Narrative genre and I appreciate it. I also hope that the book serves as an example to other birders and publishing houses that there is a place and a market for state/province Big Year books.

Adventures of a Louisiana Birder: One Year, Two Wings, Three Hundred Species is an enjoyable memoir about birding, birding strategies, birding people, community, life and death, and Louisiana (with some Alabama thrown into the mix). If like me you’ve birded Louisiana I expect you’ll enjoy re-visiting these places and learning about the ones you missed and will perhaps bird in the future. If you haven’t birded Louisiana, reading about Marybeth and Lynn’s adventures is a good place to start.

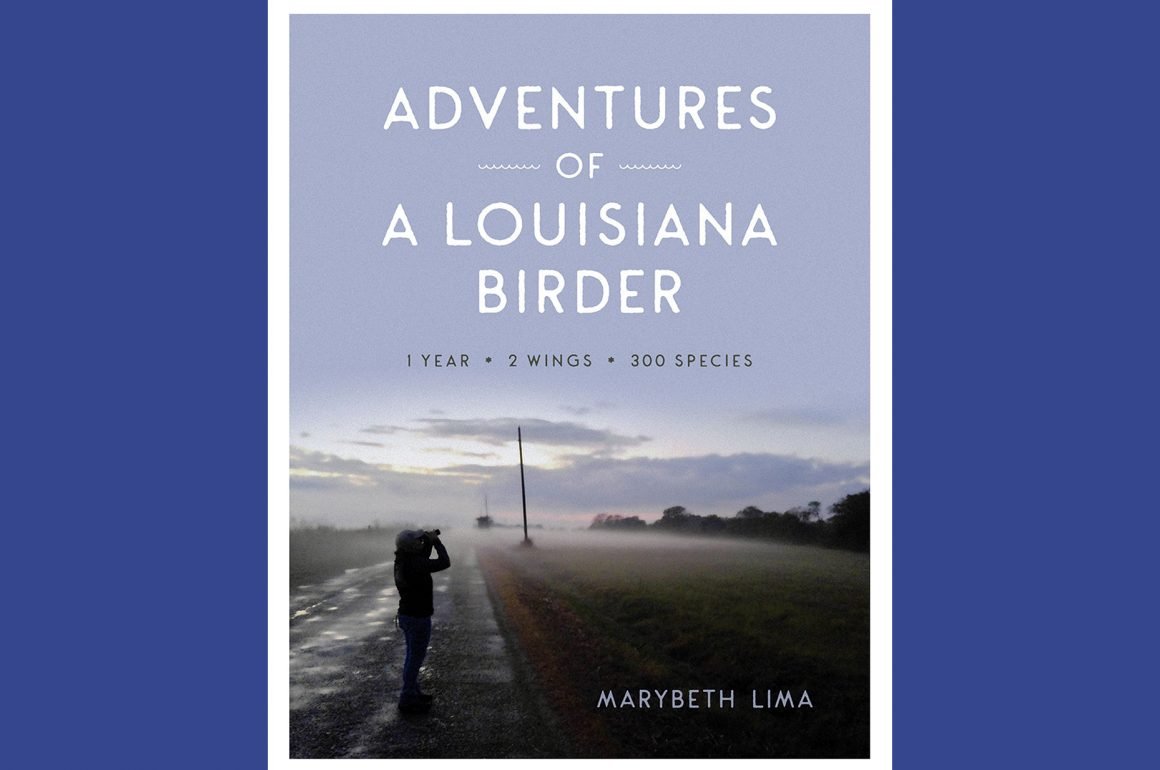

Adventures of a Louisiana Birder: One Year, Two Wings, Three Hundred Species

by Marybeth Lima

LSU Press, 2019, 272 pp.

ISBN-10 : 0807171379; ISBN-13 : 978-0807171370

$39.95 (slight discount through the usual sources); available in Kindle & ebook formats

I loved this book! I have read a dozen or more “Big Year” books and this is, without a doubt, one of the best. As the reviewer states, it is a treasure in many different aspects. I encourage all birders to read it.