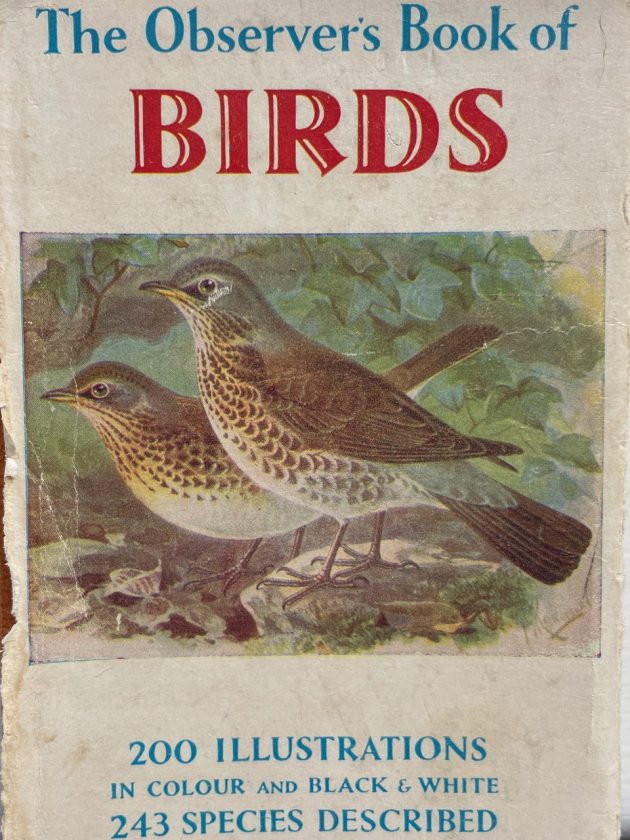

As a small child I was fascinated by animals, but it was when a pair of Blackbirds nested close to the house that I really became interested in birds. I wanted to learn more about them, so my parents gave me the five shillings I needed to buy my first bird book: The Observer’s Book of Birds. This charming little book was first published in 1937: my copy was the new edition, which came out in January 1952. I was five when I acquired my book, and within very little time I had read every page, and absorbed numerous facts and figures. I’d studied the illustrations, too – they were in both colour and black and white, and painted by the leading birds artists of the early 20th century, principally J.G. Keulemans (a Dutch artist who lived in England) and Archibald Thorburn.

First published in 1937, the Observer’s Book of Birds remained in print for many years. This cover illustration of Fieldfares was the work of the Dutch illustrator John G. Kuelemans

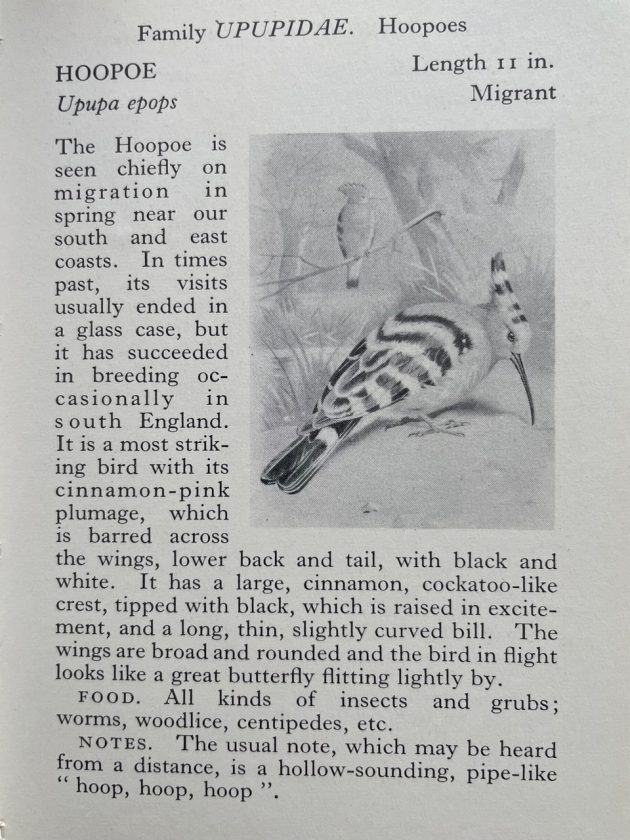

I would look wistfully at the picture of the Hoopoe, a bird I could only dream of seeing, or the elusive Bittern, but I soon learnt all the familiar birds I could find around my home, such as Linnets and Goldfinches, Swallows and Swifts. The text was written by S.Vere Benson, the Hon. Sec. of the Bird-Lovers’ League. The S apparently stood for Stephana, but she never allowed her full name to be printed. I am sure that she must have been a formidable lady of strong opinions. She described the Cuckoo, for example, as not being an admirable bird, “being polyandrous and a parasite, without care for its young”, while the Sparrowhawk “is one of the worst enemies of its tribe to small birds”. She describes the introduced Little Owl as “a fierce little foreigner”, while the Kingfisher is “a gem among birds, so brightly coloured as almost to dazzle the eye in certain lights”.

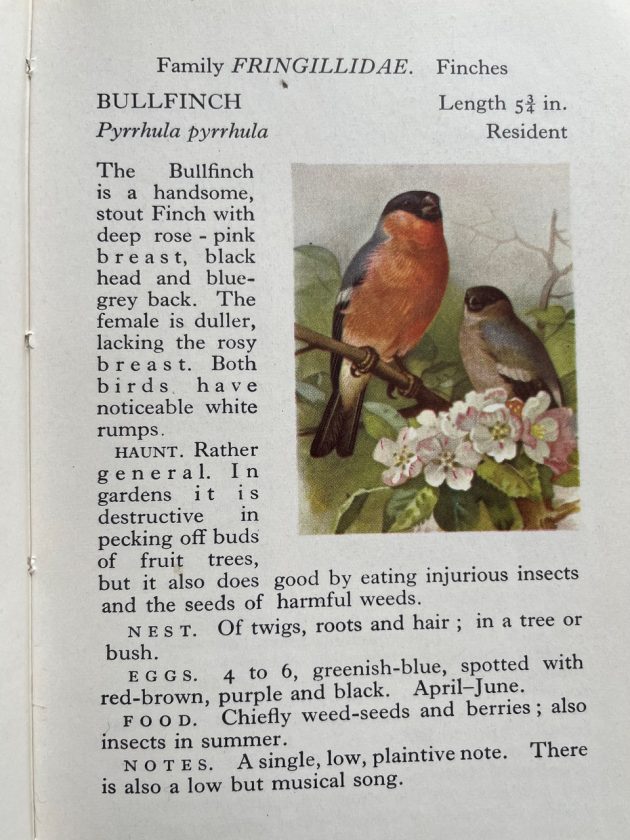

The texts in the Observer’s Book of Birds are informative but simple

All the major species were illustrated, described, then provided with details of their Haunt, Nest, Eggs, Food and Notes (song). I love the word haunt, which is very much a word of its time, and fell from use years ago. Browsing through the book brings back memories of the delight of my early days finding birds, such as seeing my first Lesser Spotted Woodpecker in a friend’s garden, then reading about it in the book. That woodpecker was, I remember, in an apple tree: I read that this “tiny woodpecker… may be distinguished by its small size”, while its Haunt was simply “Among trees”.

Not all the species in the Observer’s Book of Birds were illustrated in colour. The Hoopoe was one species that would have been much better in colour

Miss Benson’s strongest point was undoubtedly describing bird calls (their so-called notes). How better could you describe the song of the Nightjar than “A purring sound like a sewing-machine working”, or the Spotted Flycatcher’s “high squeak, like a wheelbarrow with a rusty wheel”? As for the Bearded Tit, “A twanging ‘ping’” describes it perfectly.

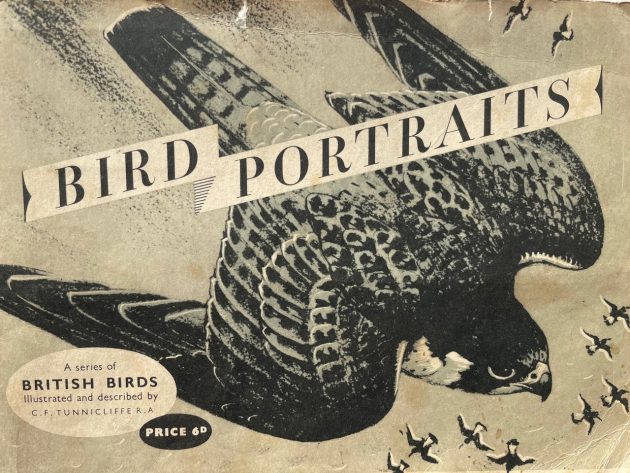

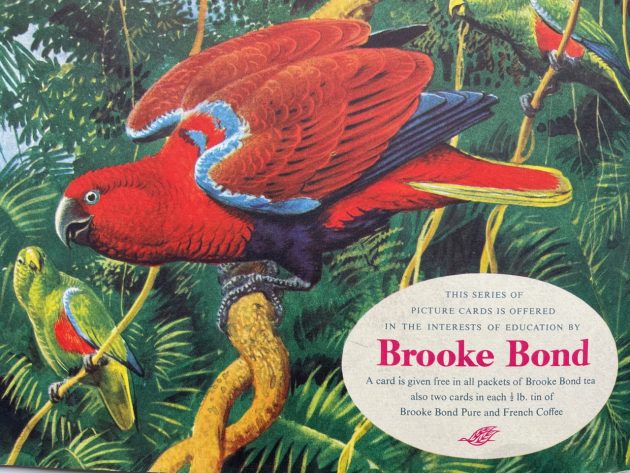

The album for Bird Portraits (1957). It was illustrated by a series of 50 cards: a single card was given free in every packet of Brooke Bond P.G.Tips Tea, but collecting the whole set could take many months

Almost as great an influence in my early interest in birds were the cards given away “in the interests of education” in packets of Brooke Bond P.G.Tips tea. Bird Portraits, a series of British birds illustrated and described by C.F.Tunnicliffe RA, was inspirational. I still regard Charles Tunnicliffe as one of the greatest of British bird artists, and everyone of the 50 cards in the Bird Portraits series is a delight, from the imperious Peregrine Falcon, perched on a cliff with a clump of sea pink, to the Red Grouse flying over a rugged heather moor. As a small boy I collected the cards avidly, swapping cards I had duplicates of with friends at school for those I was still missing. I’ve still got my original Bird Portraits album, each card glued into its allotted space.

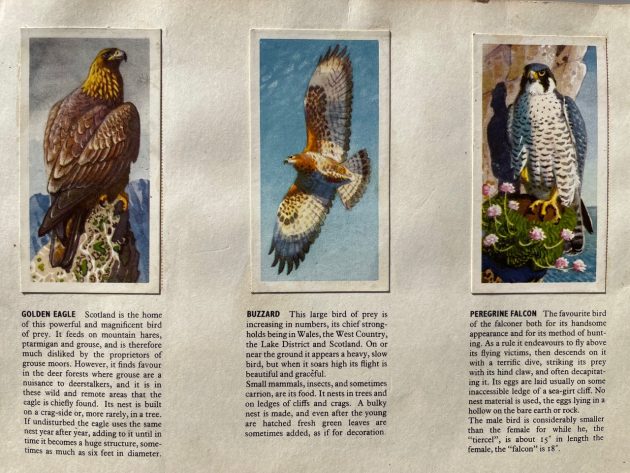

A trio of raptors from Tunnicliffe’s British Birds

I’ve no doubt the Tunnicliffe must have pondered long and hard which birds to select for the 50 birds featured. I wouldn’t be surprised if he chose the birds he best liked to illustrate. His choice ranged from the House Sparrow to the Golden Eagle, and most of the birds are those readily encountered in the British Isles. There are a few surprises though, such as the Roseate Tern, by far the rarest of the five species that nest in Britain. His choice might be explained by the fact that he lived on the Welsh island of Anglesey, which then still had a small number of nesting Roseate Terns.

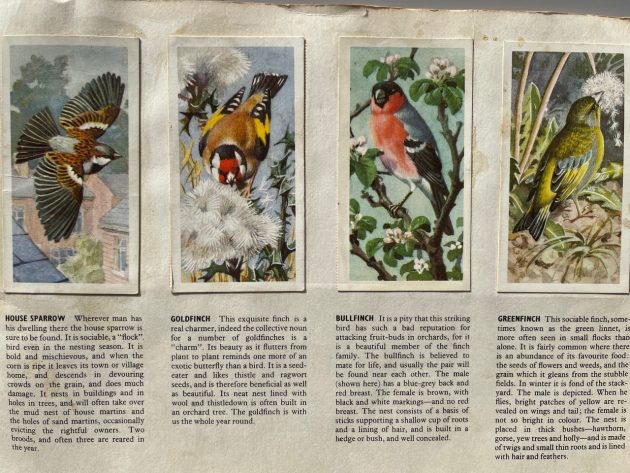

Charles Tunnicliffe’s illustrations for British Birds have a special charm

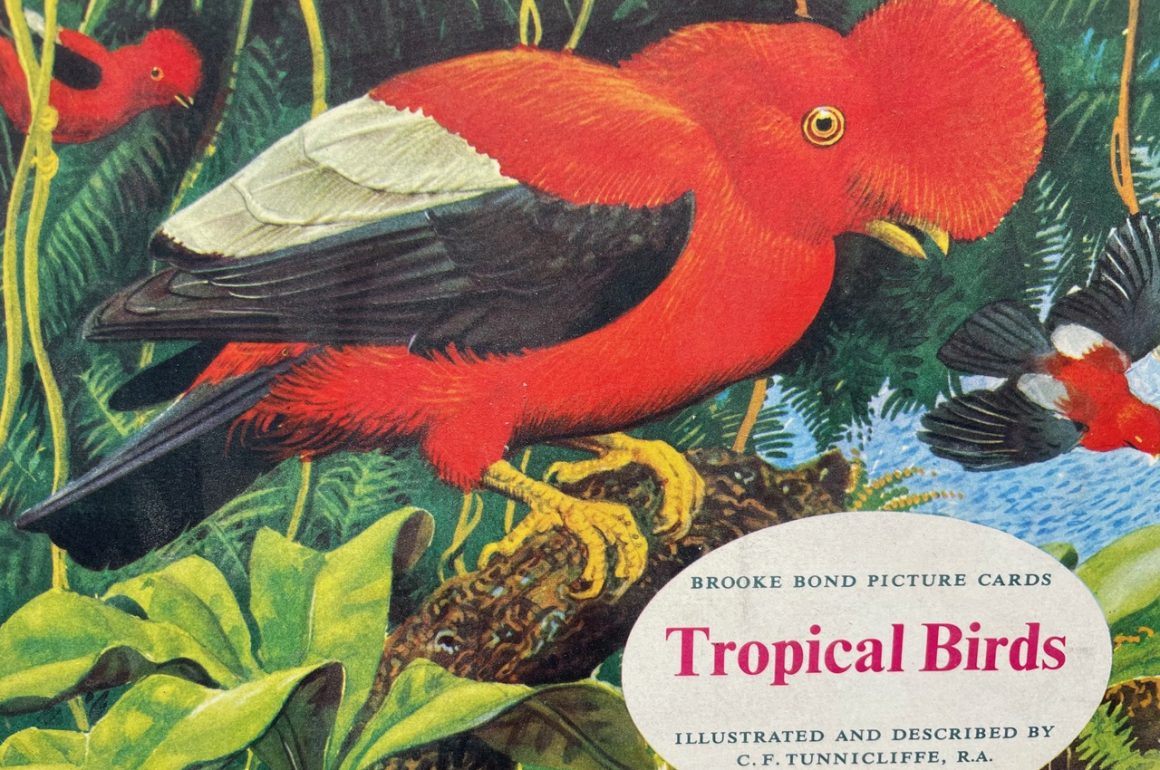

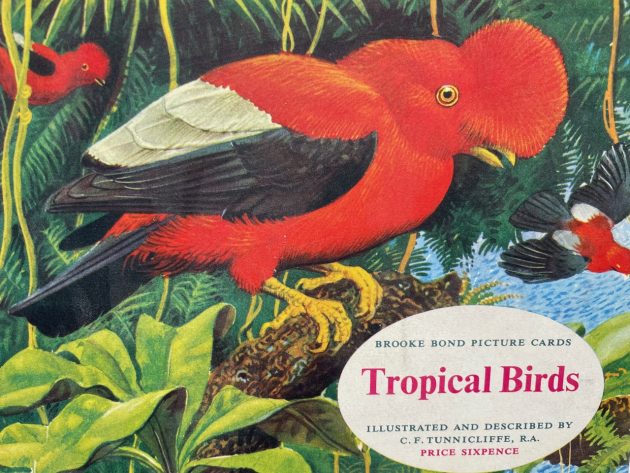

The success of British Birds led to Tropical Birds. Note the more colourful cover to the album, compared with the earlier British Birds. The bird depicted is a Cock of the Rock

Tunnicliffe was an artist not a writer, but his short, pithy texts are excellent, capturing the essential details of each of the 50 birds featured in the series. British Birds was so successful that it was eventually followed by Tropical Birds.

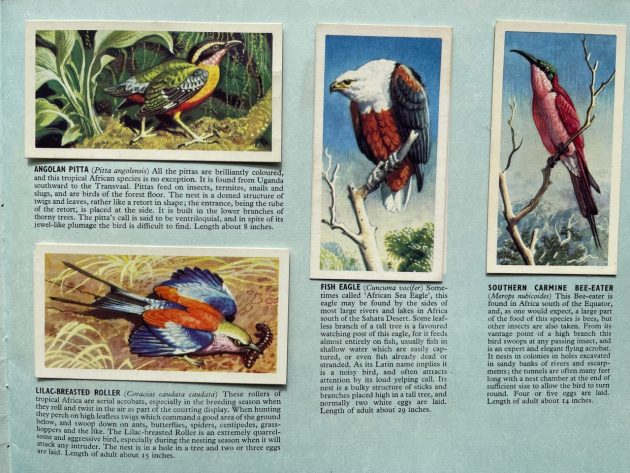

African exotics from Tunnicliffe’s Tropical Birds. I’ve never been fortunate enough to have seen the Angolan Pitta, one of Africa’s most elusive birds

Many of the birds featured in Tropical Birds I have seen in the wild, ranging from the Bateleur Eagle to the Magnificent Frigate Bird, but ever since I first looked at Tunnicliffe’s portrait of a Scarlet Cock of the Rock it’s been my ambition to see one “in the deep forests of northern Peru and the upper reaches of the Amazon” where “the flame-coloured birds have their home”. Sadly, I’ve yet to travel to the Amazon. I also have to admit that despite my enthusiasm for collecting Brooke Bond’s tea cards, I never became a tea drinker, so I’m not really a typical Englishman.

To be concluded.

Completely understanding the nostalgia of this piece, wonderful writing.

It’s interesting how an early picture can capture us for life. Back in the 50s–early 60s the Gannet was featured in something like Radio Times, or perhaps the Childrens Newspaper (or whatever it was called). I loved the elegant outlines on the head and bill, and was thrilled to see them in person — and am still thrilled to see the single bird in the Pacific, which happens to be near me and is familiarly referred to as Morris.