You wrote a book about a year in the life of a Little Tern colony, “Clinging to the Edge”. Can you tell us a bit about what you describe in your book and why you wrote it?

The heart of the book is a month-by-month account of one breeding season in the life of this vulnerable summer migrant with all that entails in terms of protecting and monitoring the birds: 24/7 wardening, electric fencing operation, data-gathering, beach-cleaning, ringing (banding), public engagement and so on.

The colony in question is on the coast of Yorkshire, the UK’s biggest county, near a unique and magical place called Spurn Point – and as the book grew I found a wanted to write about sense of place too – its geography, its natural and human culture. And inevitably larger questions arose to do with conservation and our whole relationship with the natural world. So the book grew, but retained, I hope, a sense of a ground-level approach: I wrote it for people like me really: enthusiastic volunteers, citizen scientists… and I hope there’s something in it for students and early-career conservationists too.

The Beacon Ponds Little Tern colony, pictured from the south in midsummer. As well as the Little Terns, also breeding here are Ringed Plovers, Oystercatchers, Avocets and Black-headed Gulls. Among other species caught in the frame are Common, Arctic and Sandwich Terns, though only Common Terns attempt to breed.

What makes Little Terns special for you?

Qualities, characteristics and behaviours which aren’t unique to them but which they enshrine particularly well: their 8000 mile round-trip to and from West Africa, set against their small size and apparent fragility; their behavioural complexity, from courtship to fledging; their struggles against whole range of ground and avian predators; their aesthetic appeal and so on.

An adult prospects for a nest site. She eventually settled here and produced two chicks.

To play the devil’s advocate, are Little Terns – which are classified as Least Concern – really worth all this effort?

Well, they’re classified as Least Concern at the moment… I think with the current global crises in nature we can’t afford to be complacent about the health of any natural population. One of the things the book deals with is the horrific impact of avian flu on our seabird populations that year. Our Little Terns escaped it, but there’s no saying they always will. Conservation aims to be preventive – and our Little Tern population in the UK might be stable at the moment but it is low from an historical perspective and for all our efforts isn’t growing – unlike the threats to them. If our colony collapsed, there would be an impact on other UK colonies many of which are already under pressure. There’s always a danger of the domino effect.

It’s not just the terns we protect in the colony, either: there are breeding populations of Ringed Plovers and Oystercatchers too, both of which are declining. And the data we gather on all of them is passed on to the big conservation organisations for research purposes. I also feel, quite strongly, that we have a moral duty to try to defend nature from the onslaught we have ourselves launched against it.

An Oystercatcher about to settle on her nest

What are the biggest threats to the Little Terns in your colony?

Loss of habitat because of human disturbance. The terns need the kind of sandy and gravelly beaches we use for our leisure activities: sun-bathing, fishing, walking for exercise or with dogs, fossil-hunting and so on. More than that, the relentless development of coastal infrastructure – harbours, marinas, docks, terminals, housing, roads and all that’s associated eats away at the places terns need. They have quite precise requirements, and don’t adapt very easily.

And that’s before we get to the issue of their natural predators!

Little Tern eggs in their scrape

What aspects of your volunteer work at the tern colony do you particularly like and dislike?

There’s a lot of administration and fund raising to do. Thankfully others, more qualified than me, do the great bulk of it, but it’s still frustrating. The land the colony occupies has changing patterns of ownership to deal with and our work has to answer to two different government bodies. Fund-raising is endless, and negotiating the different criteria of awarding bodies takes a lot of effort. It could all be so much simpler, and hence so much more efficient and effective.

As to what I like – everything else, from actually protecting the birds to the folk I work with and the beauty of the place itself!

A tern chick, only a few days old, getting its metal ring during our late July walk-through

Isn’t watching a tern colony for hours and hours sometimes just a bit boring?

Yes! But you keep your eyes on the horizon, literally and metaphorically. And there’s nearly always something to watch even if you are not counting birds, recording your data, scaring predators off or chatting to the passing public. Odd bits of behaviour, other aspects of the natural world… And just being there.

Some of the photos in your book reminded me how cute Little Tern chicks can be. Is cuteness also a motivational factor for you?

Not in itself: ugly things need protecting too ! But it is hard not to get attached to the birds – their struggles against the weather, predators, us; the complexities of their behaviour, their simple beauty.

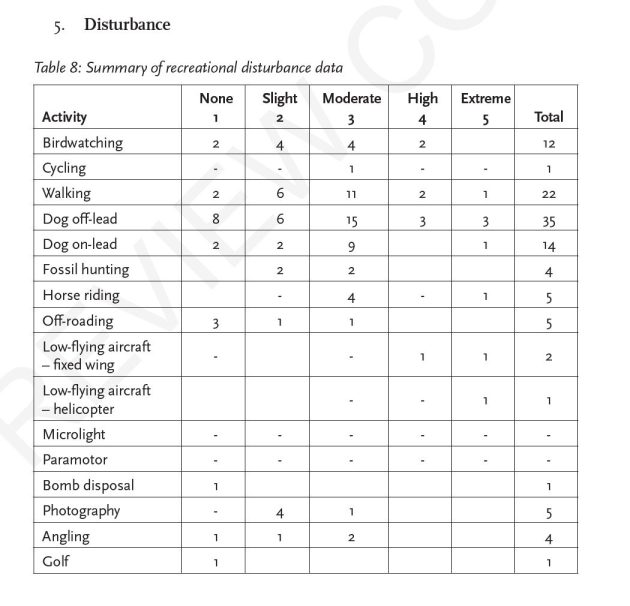

As a cat owner, I was glad to read that dogs seem to create the most disturbances at your colony, even more than that other obnoxious creature, the birdwatcher …

Summary of recreational disturbance data

Cats aren’t a problem for us: we’re pretty isolated from their ‘natural’ habitat of local farms and villages. But one rampaging dog can finish a colony for a whole season. Most birders are understanding and supportive, though a few – photographers, usually – are tempted too close.

Too close …

“Clinging to the Edge: A Year in the Life of a Little Tern Colony”

By Richard Boon

To be published by Pelagic Publishing on Nov 15, 2024

ISBN-13: 978-1784274894

Risking pedantry and before we get any complaints from Scotland: Highland, in Scotland, is the UK’s biggest county. Yorkshire is the biggest in England.