To birders, the search for raptors perched at the very tops of telephone poles, or for neatly arranged rows of sparrows or buntings sitting on the low-slung lines draped between them is one of the chief joys of any drive through the country. The tendency of birds to alight onto the wooden posts, steel towers, and metal wires that constitute our power and communications infrastructure turns any car ride into exciting and endless game of drive-by identification. Cruising along, we crane our necks, puzzled at first, squinting skyward through the grimy windshield at the distant speck on the wire up ahead – “Is that a bird?” – becoming more hopeful as we speed closer, trying to catch a glimpse of any telltale field mark – “Y’know, that kinda looks like a meadowlark from here…” – with resignation finally setting in as the true identification is revealed in a fleeting instant at 50 miles per hour – “Never mind – just another starling.” And we move on to the next speck looming ahead and the game repeats itself, over and over.

A common sight to all birders: the bird on the wire. This Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) was a life bird for me at the Salton Sea in California in 2018.

Utility poles and wires have become such obvious perches and nesting spots for birds that it’s hard to remember that our feathered friends have been availing themselves of this convenience for only about 175 years. Wooden poles were first used to suspend electric telegraph wires along the tracks of Britain’s Great Western Railway in 1843, using a system patented by William Forthergill Cooke. In the following year, American telegraph pioneer Samuel Morse encountered such difficulty in his original plan to lay underground telegraph cable between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. that he had several miles already buried dug up and the entire system strung overhead on poles. The utility pole and the gossamer wires threaded between them have been part of the global landscape ever since, imposing a regular web of horizontal and vertical geometry over our increasingly electrified world.

Utility poles have been with us for some time: Vincent van Gogh depicted some in this 1888 roadside sketch. But history doesn’t seem to have recorded which species of bird first dared to land on an electrical wire.

Birds may have taken to these artificial perches like ducks to water, but human reactions to the newfangled poles and wires were hardly as appreciative, especially in the early day. As Daniel L. Wuebben relates in Power-Lined: Electricity, Landscape, and the American Mind, noted American architect and urban planner E.H. Bennett alleged in 1925 that American cities had been “rendered hideous by poles of every kind.” Quite aside of aesthetic concerns, this new infrastructure could be dangerous as well – even deadly. The “Electric Wire Panic” of 1889, which saw the horrific deaths of several electrical linemen in Buffalo and New York City, did little to quell public fears about the overhead tangles of wires proliferating in the rapidly electrifying metropolises of the late 19th century – but it did help settle the “War of the Currents” and usher in a new age of much-needed regulation. Today, even as technological progress untethers us with more and more wireless applications each year, up to 185 million utility poles remain erected across the United States alone as permanent vestiges on our landscape.

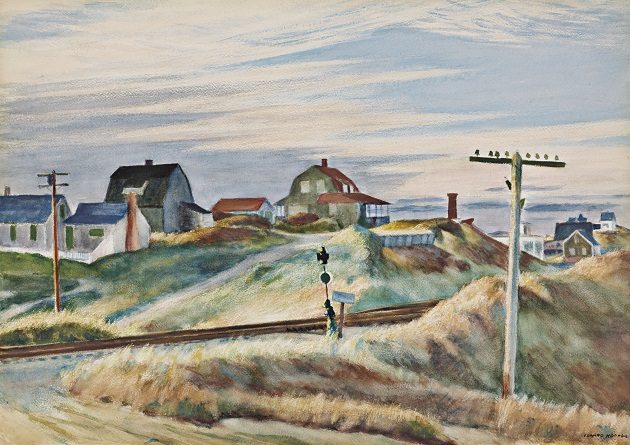

Utility poles have been an unavoidable element of the modern world, signifying the ubiquitous imposition of technology across the landscape, as in this 1938 watercolor by Edward Hopper.

While utility poles and lines provide benefits to birds, there are obvious hazards in their interactions with this infrastructure – namely, the risk of fatal electric shock. Probably every schoolchild (and many an adult) has wondered at some time how birds can sit on live utility wires without being electrocuted. The answer is that – thanks to the tendency of electricity to travel along paths of least resistance – these high-voltage perches are safe to use as long as the birds avoid becoming conductors between two wires, or between a wire and the ground (usually by touching the pole and a wire simultaneously). But electrocutions do happen, most often to larger birds that are more likely to inadvertently touch two lines at once, like hawks, owls, cranes, herons, egrets, and storks. There’s also the risk of fatal collisions, as hard-to-see overhead wires are strung at a height at which many birds tend to fly. In North America, the United States Fish & Wildlife Service estimates that up to 57 million birds perish every year in collisions with electrical utility lines. It’s a serious problem being addressed by conservationists, and there’s even an Avian Power Line Interaction Committee that seeks to reduce the frequency of these fatal accidents.

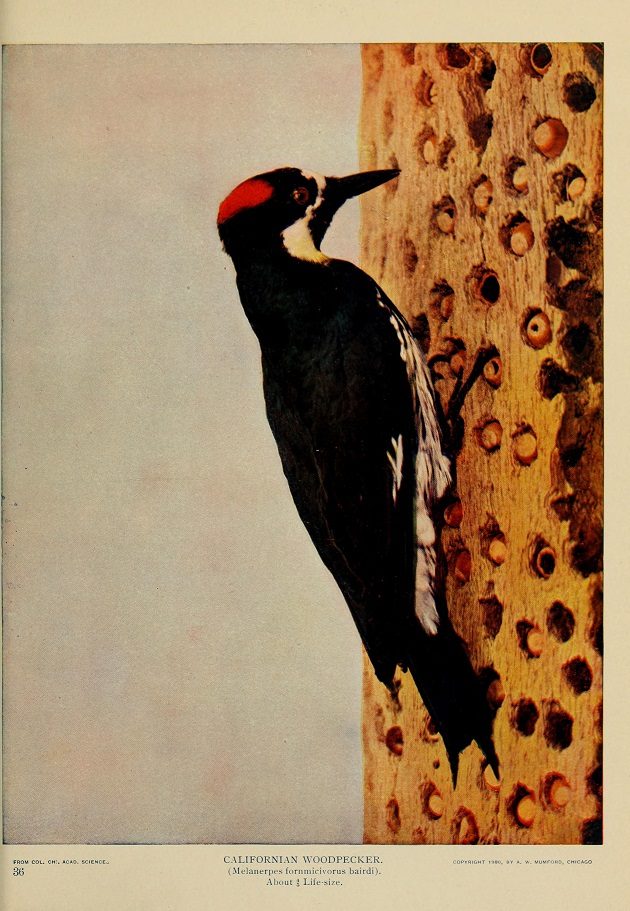

We humans tend not to think of utility poles and wires as “beautiful” or “natural” elements of the environment, when we notice them at all. But to many birds, they’re just as good as any tree, providing the requisite vertical and horizontal approximations of trunk and branch. They’re often even made of trees (mostly Southern Yellow Pine in North America, though many other tall and straight species will also do) and so attract many of the same critters some birds like to eat. Woodpeckers are especially fond of wooden utility poles, both for nesting and feeding, and the damage they and other birds cause to utility infrastructure is a serious problem for telephone and electricity companies.

This photograph of an Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) from 1900 shows that birds have been using utility poles as perches, nesting platforms, and food warehouses for quite some time.

There is an undeniable appeal to the sight of a bird sitting on a wire. Perhaps it’s the carefree bearing they assume up there, sitting high in the breeze, out in the open without any of the concealing foliage they might otherwise be hiding behind, with millions of lethal electrons coursing under their feet. Or maybe it’s reassuring for us to see birds so readily adapting to the ungainly structures we impose on their world, making some use of our towers of metal and wood. There’s also the simple visual charm of a lone bird sitting on a wire, interrupting the dull geometry of our mundane infrastructure with its feathery silhouette. It’s this image that serves as the inspiration for this week’s beer, a New England-style India pale ale made in collaboration between the Aslin Beer Company of Herndon, Virginia and Two Roads Brewing Company of Stratford, Connecticut called Under the Wire.

Under the Wire is a soft, floral, and fruity beer, with bright flashes of lemongrass, tangerine, and pine on the nose. Peaches, cantaloupe, grapes, and pineapple come through with each sip, though there’s a light touch of malt countering all this luscious fruit. Under the Wire ends with a slightly sweet, candied citrus finish with just a hint of pithy bitterness.

Under the Wire may be the only beer out there that features the improbable relationship between birds, our electrical wires, and the wooden poles that support them both. Perhaps just as unlikely is the appearance of the utility pole in literature, yet here’s a 1963 poem by John Updike titled “Telephone Poles”. It makes a far better conclusion to this than anything I could write – and I’m sure it pairs well with a nice, summery beer like Under the Wire or anything else you may be enjoying at the moment:

They have been with us a long time.

They will outlast the elms.

Our eyes, like the eyes of a savage sieving the trees

In his search for game,

Run through them. They blend along small-town streets

Like a race of giants that have faded into mere mythology.

Our eyes, washed clean of belief,

Lift incredulous to their fearsome crowns of bolts, trusses, struts, nuts, insulators, and such

Barnacles as compose

These weathered encrustations of electrical debris¬

Each a Gorgon’s head, which, seized right,

Could stun us to stone.

Yet they are ours. We made them.

See here, where the cleats of linemen

Have roughened a second bark

Onto the bald trunk. And these spikes

Have been driven sideways at intervals handy for human legs.

The Nature of our construction is in every way

A better fit than the Nature it displaces

What other tree can you climb where the birds’ twitter,

Unscrambled, is English? True, their thin shade is negligible,

But then again there is not that tragic autumnal

Casting-off of leaves to outface annually.

These giants are more constant than evergreens

By being never green.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Leave a Comment