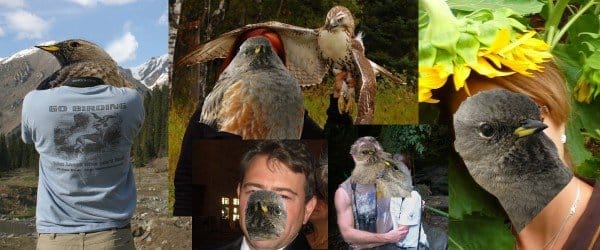

Sharon has 3 children, sired by either Corey, Mike or Kenn**; but she is not that concerned because Dawn suspects that her 17 little ones might not only have been from these three young males, as there were also many visits by Jochen and many a pleasant afternoon spent with Charlie, who now lives in another area. Dawn and Sharon are neighbours, but the males move freely through and between the two areas. And their Facebook status is always stuck on “its complicated” – a stable marriage of three males and two females. Nice.

((** all names have been changed to protect identities and have been substituted with (almost) randomly chosen substitutes suitable for a family of Alpine Accentors.))

Over the next few days, the Alpine Accentors (Prunella collaris) will arrive on their high-Alpine breeding grounds – it is time to start singing, despite that the treeless Alpine landscape is still under metres of snow. At first, they seem to “stage” in the general area of their breeding territories, feeding in skiing resorts or anywhere else where the snow is a little more open and food is a little more available. Over the next month, they will spend more and more time singing in their breeding territories, and travelling to feed in other areas, up until they can find enough food within their territories:

typical Alpine Accentor (Prunella collaris) habitat at breeding time

typical Alpine Accentor (Prunella collaris) habitat at breeding time

So you have probably come across cases of Polygyny (one male, multiple females), as in the case of lions, Red-winged Blackbirds or Northern Harrier; and you may even have heard of a few cases of Polyandry (one female, multiple males), such as Red Phalarope and many Jacanas.

all Alpine Accetor photos digiscoped (c) Dale Forbes. Swarovski ATM scope & Canon A590

all Alpine Accetor photos digiscoped (c) Dale Forbes. Swarovski ATM scope & Canon A590

Now Alpine Accentors have a much more interesting strategy: 3-5 males defend a single breeding territory, containing 2-3 spatially separated female Accentors. All individuals in this Polygynandrous relationship may mate with each other, but more dominant males will typically have greater access to females.

Here are two really interesting papers on the fascinating private lives of Alpine Accentors, if you would like to read a little more:

Heer, L 1996 Cooperative breeding by Alpine Accentors Prunella collaris: Polygynandry, territoriality and multiple paternity. Journal of Ornithology 137 (1): 35-51

N. B. Davies et al. 1995 The polygynandrous mating system of the alpine accentor, Prunella collaris. I. Ecological causes and reproductive conflicts. Animal Behaviour 49 (3):769-788

Polygynandry seems to be rather rare, but some examples of other species which may potentially be partially or fully polygynandrous include:

Highland Tinamou (Nothocercus bonapartei), Slaty-breasted Tinamou (Crypturellus boucardi), Great Tinamou (Tinamus major), Chilean Tinamou (Nothocercus

perdicaria), Brushland Tinamou (Nothocercus cinerascens), Spotted Nothura (Nothura maculosa) and Red-winged Tinamou (Rhyncothus rufescens) (see Brennan 2004 and references therein).

Purple Swamphen/Pukeko (Porphyrio porphyrio melanotus) (Jamieson & Craig 1987)

Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) cooperative breeders with up to 6 co-breeding males, 3 females in the same nest, and numerous non-breeding helpers (work by Koenig, Stacey, Mumme and Pitelka and references therein)

The New Zealand honeyeater-like bird, the Stitchbird / Hihi (Notiomystis cincta) (Castro, Mino, Fordham & Birkhead 1997)

Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) (Carey & Nolan 1979)

Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) (McFarland, Rimmer & Goetz 2000)

Smith’s longspur (Calcarius pictus) (Meddle, Owen-Ashley, Richardson & Wingfield 2003)

Galapagos hawk (Buteo galapagoensis) (Faaborg, Parker, DeLay, De Vries, Bednarz, Paz, Naranjo & Waite 1995 – the authors refer to the system as being cooperative polyandry but numerous authors have quoted this paper as evidence of polygynandry in the Galapagos Hawk)

Tasmanian Native Hens (Gallinula mortierii) exhibit all of monogamy, polygyny, polyandry and polygynandry in the same population (Goldizen, Buchan, Putland, Goldizen & Krebs 2000)

and the “lowland” accentor: Dunnock (Prunella modularis) (Davies, Hartley, Hatchwell & Langmore 1996 and references therein). I cannot seem to find any evidence that any of the other accentors are polygynandrous; at least some of them seem not to be.

If you know or hear of other examples, please let me know and I will add them to this list.

Happy birding,

Dale Forbes

Nobody tell Daisy, OK?

JAJAJA!

NO Comment 🙂

Yeah, polygynandry is really weird…what other species have this breeding system?

You people with your licentious ways. You disgust me. Don’t you realise there may be children reading this blog? You have warped their fragaile little minds!

Hi Dawn, any plans for this afternoon?

Yes? Oh…

Sharon?

🙂 😉

*Ahem* NOW, I know why you called me yesterday, Mr. Forbes! Under the guise of “talking optiks” but, in fact, it was really just to see if I was going to give you a hard time for this post! 😉

@Corey, Is there also a Daisy involved in this Group Marriage? We are now up to 3 males and at least 4 females (I see there is a Kim in the group photo too). These group dynamics are always hard to track, but this group seems particularly complex.

€Dawn, you are looking coy in you profile photo. Any reason?

@yourbirdoasis, I added a list of some examples which I had found. If you hear of any others, please let me know and I will add them.

@Duncan, they would only be licentious if one thought Group Marriage to be bad.

@Jogi, is that Jochen the accentor or Jochen the person trying to arrange a hook-up?

@Kim, that is exactly why I called you. I wanted to butter you up before corrupting your namesake (and image) 😉

I remember having read the excellent book from Alexandra David-Néel, who was the first european woman to travel to Lhassa in Tibet, in the 1920’s. She described in her book “My Journey to Lhasa” (1927) how, in the rugged mountain of tibet, women were commonly married to 2 men (sometimes brothers), making it easier (or simply possible?) to have and raise children.

Should we see a parallel between the alpine accentor and traditional populations of the highest mountains in the world? Do all the males provide food for the few nests, increasing the chance for all of them to transmit their DNA to the next generations?

Hi Laurent, that is a fascinating example of humans responding to difficult environmental challenges. In this case, they would be exhibiting polyandry. Might I assume that women typically bear fewer children, or fewer survive? (i.e. small families putting less pressure on the adult members of the family).

Kim~Please forgive me 🙂

@Dale: It’s “Jochen the guy who is desperate for a trip to North America”.

I’d do anything !!

@Jochen~I don’t need any more men in my life..but if you are willing to support my 17 offspring…I might think about it 🙂

@Dale~ Me? coy? 🙂

@Dawn: now, if I was a drake Mallard, I’d readily offer to look after your female offspring sired by … you know … not me.

But I am not a mallard.

🙂

🙂

So polygynandry really is rare, but I can’t believe I forgot about Acorn Woodpecker! Not only is it rare, but taxonomically all over the map. I’m guessing that there are a lot more polygynandrous species than we realize, but that we just haven’t discovered it yet due to the combination of still fairly recent advances in genetic techniques to asses breeding systems and only a handful of researchers doing this sort of work.

Would the white throated sparrow qualify for this?

@yourbirdoasis, I think one of the problems in showing polygynandry is individual identification and figuring out the complexities of the interactions. From what I understand, polygynandry is typically separated from promiscuity in that the individuals in the former are typically in some sort of bond with the other individuals (Group Marriage, to use an anthropomorphism) as opposed to sleeping around (to use another anthropomorphism).

In the case of Acorn Woodpeckers, they are cooperative breeders (as with many other polygynandrous species), which seems to predispose species to polygynandry. Cooperatively breeding species tend to have a strong alpha-pair + helpers structure with occasional beta males/females getting involved in the gene flow process.

Alpine Accentors, on the other hand, are not cooperative breeders and females typically have very little to do with each other.

All of this is just my understanding of it – I would love to be corrected by someone who knows better. In fact, that gives me an idea; maybe I should do something of an interview with a cooperative breeding specialist. That would be mighty interesting.

@Jochen, if you helped make them, you gotta take care of them!

@Laurent, I cannot find anything on White-throated Sparrows being polygynandrous. Do you know of any references for this?

yes you, Dawn, coy.

Thanks Dale, I am inclined to believe that you are right on all counts. There is much more of a ‘social structure’ that helps to characterize polygynandrous speices from those that are more obviously promiscuous. I think if you were interested in studying an unknown polygynandrous species, you might start by looking at species assumed to be promiscuous. You are also right about cooperative breeding as a sort of preadaptation (if you will) for the evolution of polygynandry from promiscuity.

Dale,

you may like to look into the social system of Eclectus roratus, an Australasian parrot.

They exhibit cooperative polyandrous behaviour, and possibly polygyandry.

Heinsohn R, Ebert D, Legge S, Peakall R. Genetic evidence for cooperative polyandry in reverse dichromatic eclectus parrots. Animal Behaviour. 2007; 74:1047-1054.

Hope this interests you 🙂