Bird Day is a lovely, little jewel of a book. The idea is to portray one bird for each hour of the day in words and art, presenting the diversity, beauty, and wonder of avian life. The partnership of its creators, ornithologist Mark E. Hauber and artist Tony Angell fulfills this goal beautifully and was the factor that motivated me to review this book. Angell’s black-and-white illustrations bring sparks of energy and visual clarity to the fascinating bird behaviors described by Huber. Each element is very good on its own, together they make a magical argument for valuing birds and learning more about them.

The scope is worldwide; of the 24 birds depicted, five are from the Americas; five from Eurasia; three from New Zealand; two from Australasia; three from Africa; one from Africa and Asia; one from Antarctica; two worldwide, and two from Asia, introduced worldwide. There is also diversity in type of species, which I think you need if you are going to portray birds in a 24-hour cycle; they range from water fowl (Common Pochard) to Galliformes (Indian Peafowl) to seabird (Cook’s Petrel) to parrots (Eclectus Parrot) to raptors (Bat Hawk) to some of our favorite passerines (American Robin and European Robin). And there is diversity in charisma–few people can resist an Emperor Penguin or a Secretary Bird, but common birds like Indian Myna and Black-crowned Night Heron also get their due respect.

© 2023 Tony Angell; © 2023 Mark E. Hauber

Hauber’s mini-essays focus on specific behaviors, enhanced by references to recent research yet written in a relaxed, personal way. Each chapter starts with the bird’s activities at that hour of the day–a Barn Owl is hunting at midnight; a female Brown-headed Cowbird is secretly laying her egg in another species’ nest at sunrise; an Ocellated Antbird is devouring insects fleeing from a swarm of army ants at noon; a male Standard-winged Nightjar is courting females in flight while also feeding on flying insects at sunset. The scope quickly widens to questions we all have when observing birds feeding, courting, nesting, flying– the why and how of it–and possible answers offered by scientific research and theory. Hauber is really good at presenting scientific findings so they don’t seem scientific at all, simply reasonable answers to our questions. He is particularly adept at explaining obligate brood parasitism, a subject he has researched extensively, for both birds that practice it (Brown-headed Cowbird at 5:00am, Common Cuckoo at 4:00pm) and host birds (American Robin at 8:00am). The essays also touch on conservation, though less that the amount I would have assumed would be in a book that is part of an “Earth Day” series.

The selections appear to largely reflect Hauber’s personal experiences around the world and he does occasionally bring himself into the essay, reflecting on a European Robin he observes at dusk in northwestern Germany or searching for American Robin nests on a tree farm in the Midwestern United States. Mark Hauber is currently (just appointed!) executive director of the Advanced Science Research Center of the City University of New York, former Harley Jones Van Cleave Professor of Host-Parasite Interactions at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign School of Integrative Biology, former professor and administrator at CUNY, and former editor of The Auk: Ornithological Advances (now called Ornithology). He has written and co-written over 400 scientific papers on brood parasitism, Common Cuckoos, egg rejection and other nesting behaviors, and fairy wren learning in addition to The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World’s Bird Species (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2014). He has spent time studying and teaching in New Zealand and more recently in Germany, which explains some of the bird choices in this book. I do wish he had included Fairywrens!

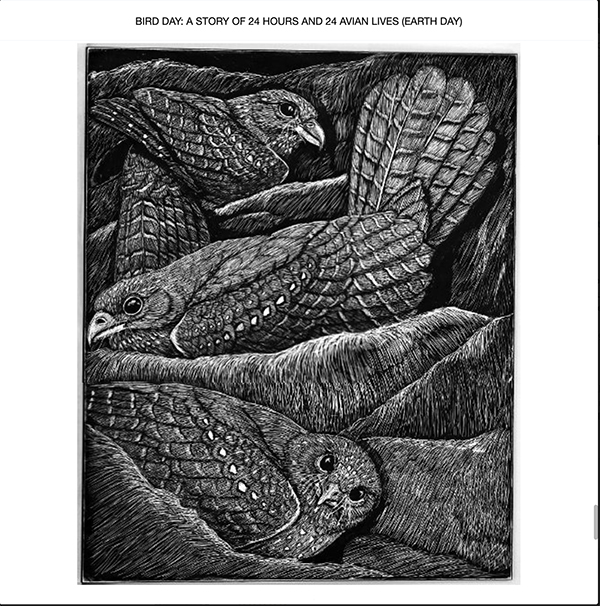

Tony Angell is one of my favorite bird artists. He is also a sculptor and a naturalist and has combined his observations with his art in past titles, notably House of Owls (2015), In the Company of Crows and Ravens (2005), and Marine Birds and Mammals of Puget Sound (1982). Angell works in black-and-white, using, from what I can tell and read, the scratchboard method, a form of engraving which involves carving lines out of dark ink to reveal a lighter layer underneath. The result is artwork that is precise yet dreamy, echoing a history of scientific illustration that relied on drawing and etching while also conveying the immediacy of the bird’s presence as seen and imaged by the artist and the writer.

Angell’s black-and-white methodology works well for crows, ravens and owls, his chosen subjects, and it also surprisingly well for more colorful birds, even Indian Peafowl. The limited palette allows the illustrations to echo the time of day of each chapter and habitat of each bird. The Barn Owl sweeps down in darkness at midnight, moonlight illuminated his wings and face. The Ocellated Antbird is shown in the company of a tropical butterfly and grasshopper and other, smaller neotropical followers of army ants, the noon light peering through vines but not reaching the darkness of the rainforest foliage-filled floor. The light is much brighter for the Superb Starlings at 3:00pm in Africa; the high ratio of white and light-gray space tells us that the sun is hitting their large, domed nest (“Their feathers shine especially bright in the afternoon sun already starting to set,” page 85), and although we can’t see the famously bright plumage, we see the difference in shading and know that they must be as spectacular as the text promises.

Black-and-white also allows Angell to play with design and shape. Emperor Penguins march in diagonals down the ice field at 2:00pm, almost like an Escher drawing except for that one happy Penguin at the bottom, sliding with glee. Oilbirds roost in their cave, forming a puzzle of shapes (see above). The Secretary Bird capturing a snake an hour earlier in Africa fills the frame with its great wings, rear plumes, eerie face, and long, scale-covered feet. This is my favorite illustration. After seeing Secretary Birds in real life enticingly faraway, it’s wonderful to see one depicted close-up in all its sexy ferocity, stomping the snake to death (and seemingly enjoying the stomping quite a lot), as described in the essay. Angell’s genius lies in finding the avian drama in Hauber’s essays without losing the detailed beauty of each bird’s plumage and anatomy.

For readers who want to learn more about the ideas Hauber sketches out–obligate brood parasite, evolutionary gain, evolutionary development of alternative senses, heterospecific eavesdropping, to name some–there is a “Further Reading” section in the back of the book, listing five excellent general bird books and “relevant peer-reviewed papers” by chapter. There is also an index, which I am very happy to see, though it could use proofreading. Personally, I am so happy that the authors and publisher understand the importance of both these items!

Bird Day: A Story of 24 Hours and 24 Avian Lives is a book that can be read by anyone. People not very interested in birds will, I hope, find that they are more than creatures who fly and build nests; beginning naturalists will find so much rich material to digest, and more experienced birders will enjoy the artwork and, I think, find information nuggets that are intriguing. The book is listed in the University of Chicago Press as the first in an “Earth Day” series, described as a series of short books offering “twenty-four chapters, corresponding to twenty-four hour-long windows to witness the diversity of life.” I’m assuming that the series seeks to elevate people’s awareness of the dangers presented by modern life and climate change and encourage conservation and environmental protection, the whole purpose of Earth Day on April 22nd. Indeed, Hauber does make this plea in his concluding chapter. I’m curious what form of life will be presented next in the series.

Bird Day: A Story of 24 Hours and 24 Avian Lives

by Mark E. Hauber; Illustrated by Tony Angell

University of Chicago Press, Dec. 2023

168 pages; 24 halftones; size: 4-3/4 x 6 inches

$18.00; also available in PDF and eBook formats

Leave a Comment