Bird pellets are wondrous things. Open them up and see tiny mammal skulls, teeny thigh bones, beetle wings, fusty feathers, squirrel hair, reptile scales, grasses, fruit seeds, maybe even bird bands and plastic bits. They’re useful resources for researching bird food sources (present and historical), relative numbers of small mammals in a bird’s prey area, and seed dispersal. And they’re a great way to get kids involved in birds and ecology, something I know from experience, when my five-year old granddaughter told me enthusiastically about how owls eat mice and you can see the bones. (It was rather ego-deflating that a pellet dissection at a birthday party could do in 20 minutes what I’ve failed to do in five years.)

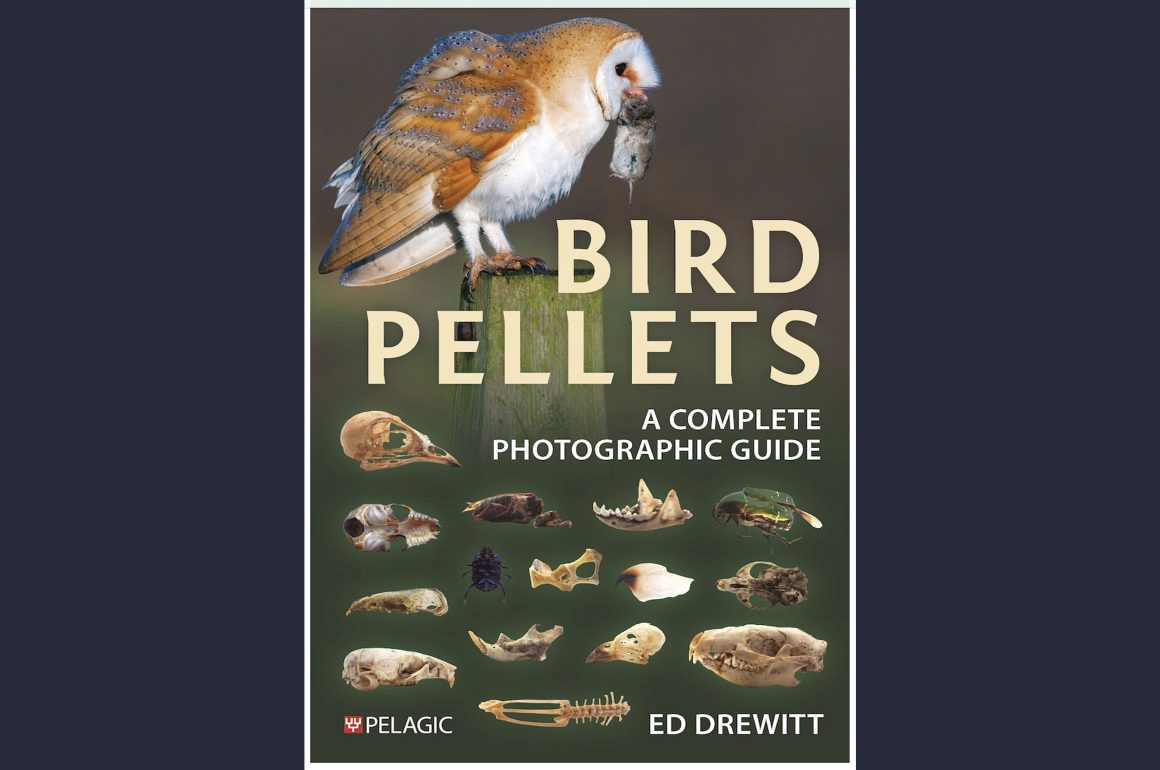

You can find some material on how to dissect owl pellets online, often in the form of a teaching module, but I don’t think a book-length guide to pellets has been published until now. Bird Pellets: A Complete Photographic Guide by Ed Drewitt is a comprehensive guide, a combination of manual and handbook, to dissecting bird pellets and identifying their contents. Published by Pelagic Publishing, an independent academic-oriented British publisher that has been coming out with titles filling unique knowledge niches, the book is oriented towards British birds and locations. Nevertheless, there is enough general material here and species overlap that it may be of interest to North American naturalists, nature educators, and birders. I’m also hoping that some of 10,000 Birds growing British audience will be reading this!

© Donna L. Schulman, 2021. Barred Owl coughing up a pellet, Central Park (this is probably the beloved ‘Barry,’ though there were a couple of Barred Owls in the area at the time).

My first exposure to owl pellets was searching for them on my bird club’s annual trip to Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx in the fall; where you found pellets, I learned, you’d find Great Horned Owls and, if we were lucky, a Barred or even Saw-whet Owl. I loved knowing that there were owls in the Bronx, familiar to many people as New York City’s symbol of urban decay. I soon learned that if I watched a Great Horned or Barred Owl long enough, in the one of their many but often secret locations in New York City, I’d see it coughing up a pellet (though I could never go looking for that pellet since that would mean getting too close to the owl). What I didn’t know till I read this book is that owls are not the only birds that cough up pellets, many bird species do, including most raptors (not Osprey), seabirds, gulls and terns, cormorants, cormorants, crows and other corvids, kingfishers, shrikes, and even garden birds like thrushes. I wonder now how many pellets I passed over thinking they were poop, not pellets.

This is actually a major part of the introduction to Bird Pellets, how to distinguish bird pellets from poop (or ‘poo,’ as it’s called here). As he does throughout the book, Drewitt offers pages of large, color photographs to illustrate his text–badger poop, hedgehog poo, fox scat, otter spraint, mink scat, woodpigeon and magpie poop. Poop is what birds defecate after digesting food, pellets are what they spit out of their mouths, the indigestible parts that have been collected in the stomach.

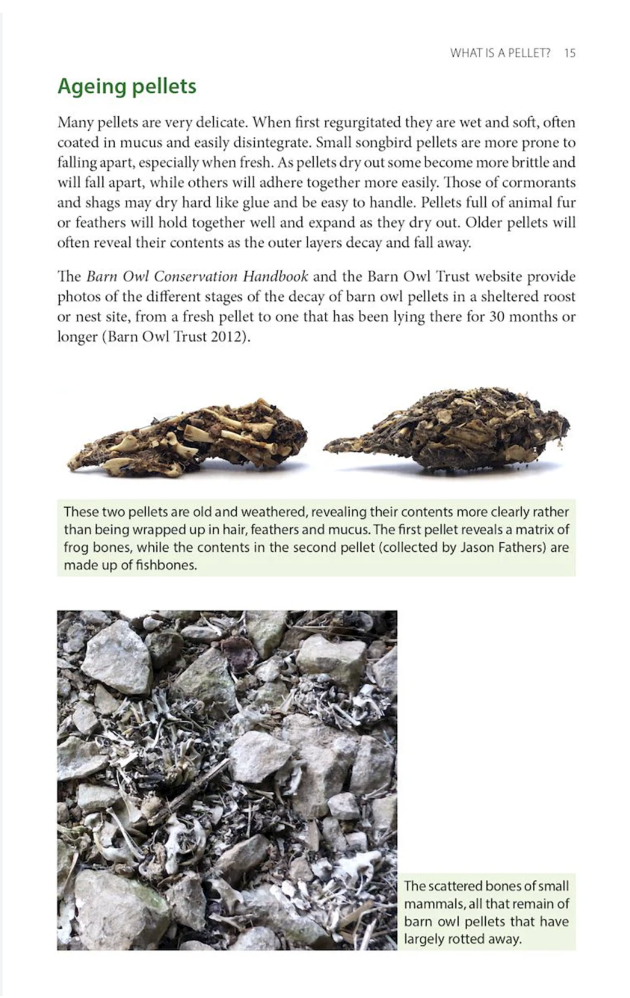

In the second introductory chapter, Drewitt describes what pellets look like in general terms (soft or rough, hairy or textured, depending on what the bird has eaten, more details given later in the book) and where to find them–generally, roost sites, but also anywhere a bird may perch, forage, or loaf. He points out, as he does throughout the book, that access to some of these sites, such as seabird colonies or tern nesting areas, may require specific permits, experience with collecting specimens from bird colonies, or simply awareness about not disturbing a roosting bird, like those owls I saw in Pelham Bay Park. Other considerations are aging the pellet (the older, the drier, the less hair and mucous), the presence of plastics (an increasing concern), and, most interesting to me, finding elements of ‘secondary consumption,’ the remains of food eaten by the bird or mammal eaten by the bird who has regurgitated the pellet.

One question I had was about the legality of collecting pellets in the United States (Drewitt cites U.K. legislation). The answer was easily found online; the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service states that under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, “Owl pellets, albatross boluses, bird feces, and similar items that are naturally regurgitated or excreted by birds are not protected provided items are collected without disturbing the bird or bird nest. Even though there is a possibility that the item may contain pieces of migratory bird species, they are primarily composed of rodents and fish. A permit is not required to possess these items; however, a permit is required if an individual is in possession of a bird when collecting these items.”

Chapter 3, ‘Dissecting your own pellets, where to begin,’ is a good introductory resource for nature educators and teachers who would like to do group projects or demonstrations. In a manual-type way, Drewitt takes us through the steps of an educational dissection, listing materials needed, cautioning about safety and health, suggesting follow-up activities, with photographs showing a pellet dissection in action. He recommends getting pellets from a local raptor organization; I’m not sure how easy that would be in the U.S. where we do have scattered raptor trusts and wildlife rescue groups, but no Barn Owl Trust. Although no specific curricula are included, there is a boxed section featuring Kate MacRae (WildlifeKate), who talks in detail about how she conducts Barn Owl pellet dissections with children. Drewitt also touches on scientific uses for pellet dissection, which may expand in the future with technologies such as metabarcoding and isotope analysis. My favorite part of this chapter is the ‘Basic guide to identification,’ which in five bullet points succinctly tells us how to know if your pellet contains a vole or a mouse or a shrew or a rat, accompanied by a terrific full-page diagram.

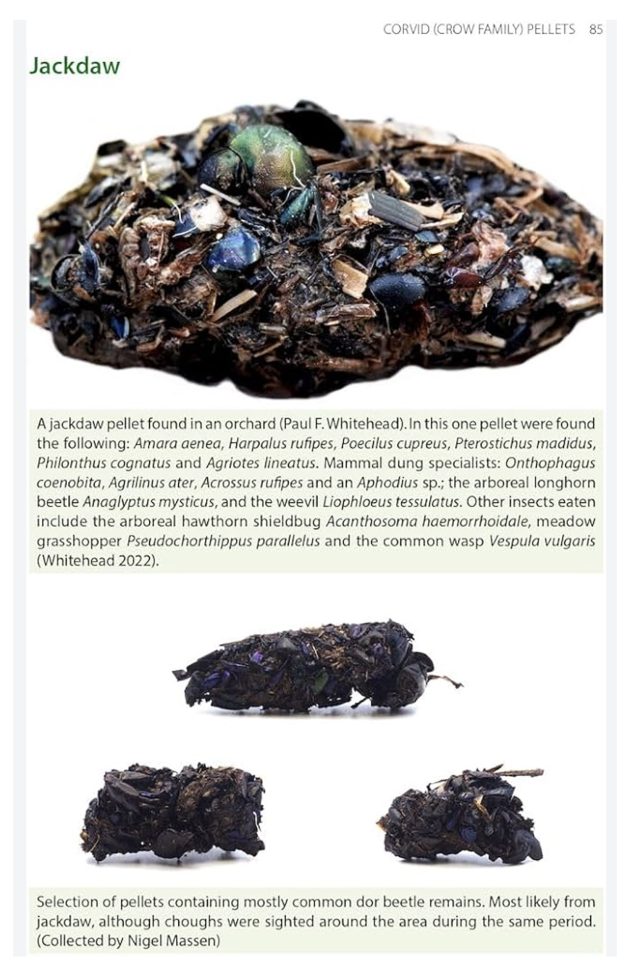

The remainder of the book is a sort of species accounts for pellets and their contents. Chapters 4 to 10 list, describe, and illustrate an amazing range of bird pellets: Owls; Corvid; Gull, tern and skua; Other seabird and waterbird; Garden bird; and Other species’ pellets. Chapter 11 is on “Identifying small mammal bones,” chapter 12 is “Identifying other small animal parts,” and chapter 13 is “What else might you find in a pellet?”. Bird species pellet accounts are organized uniformly, listing diet (an indication of what you are likely to find in its pellet); identification (what the pellet looks like–general size, shape, what is usually found in the pellet); where found; measurements of pellet; notable features (a catchall for scientific findings, likelihood of finding bird bands, similarity to other pellets, and tidbits like an unusual odor or fragility). Illustrations, most by Drewitt, are large–a quarter or half-a-page–and as colorful as could be considering most of the subject matter are brown and gray (exceptions are pellets filled with red and yellow fruit matter and white stork pellets). Some are of the pellets where they’re found in the field, giving an idea of what to look for. A fresh Goshawk pellet, for example, has a pigeon foot sticking out of it. A Jackdaw pellet was discovered by British entomologist P.F. Whitehead to contain the remains of click, woodland ground, and dung beetles, plus meadow grasshopper and common wasp.

© 2024, Ed Drewitt, p. 55, section on Jackdaw pellets.

© 2024, Ed Drewitt, p. 55, section on Jackdaw pellets.

I suspect that the mammal chapters are the ones that will enthrall nature enthusiasts and anyone who loves the cataloging of things, especially small things that rarely get any attention. A manual for identifying the bones most commonly and sometimes not so commonly found in pellets, each section describes and illustrates the skulls, jawbones, teeth, and sometimes other parts of voles, mice and rats, squirrels, dormice, rabbits and hares, shrews, bats, moles, hedgehogs, stoats and weasels. Also, how to identify the remains, which vary from vertebrae to teeth to skin, of amphibians and reptiles. And…let’s not forget insects shrimp, fish, and birds (because birds do eat birds). It’s an amazing collection of very specific, very detailed expertise. The sections on voles and shrews are lengthy, as suits the favorite prey of our raptors. All the larger mammal groups are divided into ‘species accounts,’ which include sections on what to look for quick identification, skull length range, and the ‘clincher,’ details (usually teeth details) that will confirm the identification. The book design, which leaves lots of space for illustrations, utilizes arrows to caption tiny details in the photos, and encases important identification facts in light green boxes, is a huge element is making all this information readable and accessible. The incredible number of photographs are the critical element here, and frankly my mind is blown thinking that the author drew on his personal collection for most of them. The photographic quality is pristine for the most part (a couple of the photos of very small parts are hard to make out clearly, I kept wanting to enlarge them with my fingers), helped by the high-quality paper and color printing.

Drewitt has drawn on an impressive number of scientific journal articles and handbooks for data and natural history information; they are listed in an impeccably written References section. Strangely, the section does not include a major source cited in chapter 12, a manual for identification of fossil amphibian remains that is cited instead in the chapter, and I wonder if this was a last minute addition. Other back of the book sections are Latin Names of Species and an Index (possibly the only index I’ve seen that has “poo” as a subject heading). Photographic credits for images not taken by Drewitt are given in the photographs’ captions.

Author Ed Drewitt has a resume that read like naturalist-of-all-trades (and master of many). He describes himself as “a naturalist, author, tour leader, birder, photographer, public speaker, bird ringer, zoologist, feather expert and peregrine researcher.” Previous books are Urban Peregrines (Pelagic, 2014), based on years of Peregrine research, and Raptor Prey Remains: A Guide to Identifying What’s Been Eaten by a Bird of Prey (Pelagic, 2020). He is currently studying for a Ph.D. on Peregrines and leads bird walks, fossil hunting walks in the Forest of Dean, where he lives, and does bird ringing (banding) at Pilning Wetlands and ringing demonstrations on television. Drewitt’s enthusiasm and knowledge of bird pellets, he explains in the beginning of this book, started in boyhood and became a professional interest in the mid-2010s when he worked in the teaching laboratory of the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Bird Pellets: A Complete Photographic Guide by Ed Drewitt is a unique and fascinating book, one that I think will be appreciated and used by naturalists of all ages in Great Britain, particularly nature educators and birders who love owls and raptors. I think it would also be helpful to nature educators in North America, though I’m hoping someone somewhere will be inspired to write our own guide to bird pellets. Till then, I’ll be looking down a lot more as I bird, trying to figure out which lumps are poop and which are pellets.

Bird Pellets: A Complete Photographic Guide

by Ed Drewitt

Series: Pelagic Identification Guides

Pelagic Publishing, June 2024; 250 pages, 685 illustrations

ISBN-10 : 1784274712; ISBN-13 : 978-1784274719

Paperback, $38.00 (from publisher); Kindle, $30.49 (from Amazon)

Leave a Comment