“They charm the females by instrumental music of the most varied kinds”

And thus, Charles Darwin adapted the phrase “Instrumental Music,” previously used to mean humans with instruments making music, to name one of the most important “secondary sexual characters … diversified and conspicuous in birds” which, added to “all sorts of combs, wattles, protuberances, horns, air-distended sacs, topknots, naked shafts, plumes and lengthened feathers gracefully springing from all parts of the body” mediate avian sexual selection1.

Bird “instrumental music” is bird song. Bird song is defined in various ways, but I prefer the functional definition used by evolutionary biologists. A bird song is a communication having to do with sexual selection. The modal bird song is made by a male to signal his quality to females who are busy choosing among a number of possible nest mates. That same song may be thought of as a territorial marker, but the territorial nature of bird song is probably more of an atavism than a demonstrated fact. If keeping other males away is a function of song, it is probably a secondary one. The song is better thought of as a quality of the territory and the male, and that quality indicator may well have ‘meaning’ to both male and female birds.

The modal bird song is a song, but not all ‘songs’ are song-like, in the sense that we expect song to come out of the ‘mouth’ (bill) and to consist of modulated air currents (like human voice). Just as human language is not always spoken (it can be signed, for instance, or in some cases, transmitted with a certain look) “bird song” may be generated by beating of feathers, clattering of a bill, or some other noise-making somatic activity.

One of the most spectacular examples of communication among birds that is all about mating but involves no song is the bower and gifts assembled by the male bower bird, where just like in humans, a nice place to hang out, a pile of cool but useless presents, and excellent dancing often leads to a second date.

Drawing of bower birds from Darwin’s 1871 volume on sexual selection.

Just as importantly, not all bird sounds are bird songs. One of the (undesirable, in my view) definitions of bird song is that it must be complex. Thus, the cooing sound of a pigeon is not a bird song. But it is, if it is what Male pigeons do in relation to mating and sexual selection. But other sounds, like the hard to localize tsick tsick of nuthatches or chickadees which we may refer to as “contact calls” are not songs. They are modulated air streams coming out of the beak, they are sounds, they may have a role in the percussion section of the “instrumental music” of the avian cacophony, and they may even be social communication at that, but no matter how sexy a nuthatch’s tsick tsick may be to a birder who has not seen a nuthatch in a while, it is not going to get the bird a date or even a glance (well, not that kind of glance).

So defined, bird songs are the sounds, often but not always loud and musical, that (mostly) male birds make as part of that species’ mating system. This kind of vocalization may have evolved a few different times, though I for one am not going out on a limb to explain what some call “songs” in hummingbirds or parrots. If we think of bird songs as whatever sounds male birds make for mating purposes, then there are far more parallel examples among the birds. If we require that bird songs sound like the sounds that “song birds” make, then, well, this behavior evolved once, in the song birds (duh). Sticking strictly with the usually melodious and mating related form of the behavior, as is found in the Passeriformes is a good bet and allows us to talk about a well studied and understood phenomenon.

These bird songs have two aspects, and I oversimplify but not excessively so: A genetically inherited template, usually specific to the song-producing sex, and a learned song that consists of the template shaped by experience as a developing bird hears the adult version of its own song. The templates can be discovered by raising birds in the absence of adult song, and they often sound very little like the normal final product.

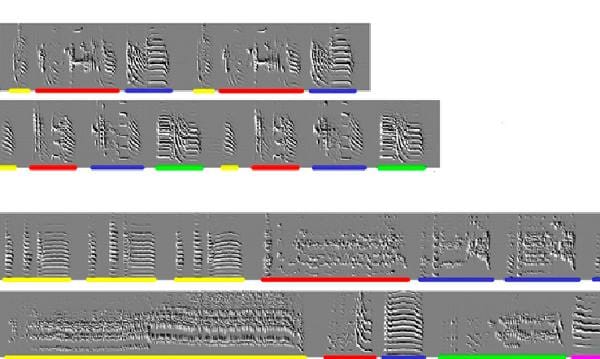

These are sonograms representing the song of four Zebra Finches. The top two are individuals with normal song. The bottom two are the songs of individuals raised in isolation, representing only their “built-in” template unaffected by the experience of hearing normal adults.

In these song birds, we often see dialect differences between regions. If a hatchling is raised in the region in which a dialect other than that of its parents is used, it will develop its genetically determined and undifferentiated template into the dialect used in the area to which it is moved, just like a French infant conceived of French-speaking humans in Paris but raised by Americans in Dallas, Texas will speak English.

The most important thing about this is the following: The parts of the bird song that determine the Darwinian success of a bird … via its ability to find a mate or to do whatever else we find the bird is doing with its song … is not determined mainly or even measurably by the template for that song. It is, rather, determined by its correct learning of the song as it is sung locally by members of its species, plus other non-genetic factors we will not investigate today.

This is important because when we think about evolution, we often (because we are humans, and humans are not all that smart) immediately simplify the world into one in which organisms carry (variant copies of) genes that they (may or may not) pass on to offspring and that determine that organism’s behavior. In this simplistic view, anything that varies that is not genetic is noise. But this can not possibly describe bird song. In song birds, the song is learned, and it is learned in a way that is determined entirely by local conditions which clearly change across space from region to region, as a dialect of a widely spoken human language may vary from place to place.

Putting it a slightly different way, the template from which a bird builds its song is passed on genetically, and the song itself is passed on culturally, or if you prefer a different term, “extrasomatically” or “non-genetically” or whatever you like. But not genetically.

This parallel transmission is certainly “Darwinian” and evolutionary in both tracks. A gene that has a mutation causing the protein it expresses to be ‘broken’ in a way that messes up the bird’s template will find itself in a mute male bird and thus not be passed on. A variant of a gene that produces a template that has some sort of advantage might be passed on to more offspring. But the same is true of the song itself. Imagine starting with two sets of Zebra Finch hatchlings. One group is exposed to normal zebra finch song for a given area, the other to a fake bird song that is sufficiently like a zebra finch to cause the birds to learn a “song” but one that would be ineffective in its social role for wild zebra finches. Now, release the finches. Which ones will contribute both their genes and their song to future generations? Unless the fake song you used in this experiment was, accidentally, an extraordinary song, the basis for the next avian idol, the birds in the second group and their ‘song’ would be evolutionary dead ends. Their genomes would be an evolutionary dead end AND their song would be an evolutionary dead end.

This parallel transmission is certainly “Darwinian” and evolutionary in both tracks. A gene that has a mutation causing the protein it expresses to be ‘broken’ in a way that messes up the bird’s template will find itself in a mute male bird and thus not be passed on. A variant of a gene that produces a template that has some sort of advantage might be passed on to more offspring. But the same is true of the song itself. Imagine starting with two sets of Zebra Finch hatchlings. One group is exposed to normal zebra finch song for a given area, the other to a fake bird song that is sufficiently like a zebra finch to cause the birds to learn a “song” but one that would be ineffective in its social role for wild zebra finches. Now, release the finches. Which ones will contribute both their genes and their song to future generations? Unless the fake song you used in this experiment was, accidentally, an extraordinary song, the basis for the next avian idol, the birds in the second group and their ‘song’ would be evolutionary dead ends. Their genomes would be an evolutionary dead end AND their song would be an evolutionary dead end.

A variant song that is hard to learn, inaudible to other birds, or that causes some sort of inappropriate response or confusion will undergo Darwinian selection just as a variant gene that causes a bird to have an ineffective template will undergo Darwinian selection. Minimally, bird songs are selected to be something a bird can generate and something another bird can hear, against the background of ambient sounds, at the distances at which these birds are communicating, and in the birds’ local cultural context.

![]() A recent series of demonstrations has been published of how plastic bird song is, and how the learned part of this parallel process of transmission can be adapted, in a Darwinian sense, just as a population of genes might be adapted, to changing conditions. Birds living in urban environments must sing against different background from their rural counterparts. Urban noise covers over sounds at certain, typical lower, frequencies, and may also drown out other sounds in general. The following studies show that there may be an effect on the bird songs (not the genes) in urban environments:

A recent series of demonstrations has been published of how plastic bird song is, and how the learned part of this parallel process of transmission can be adapted, in a Darwinian sense, just as a population of genes might be adapted, to changing conditions. Birds living in urban environments must sing against different background from their rural counterparts. Urban noise covers over sounds at certain, typical lower, frequencies, and may also drown out other sounds in general. The following studies show that there may be an effect on the bird songs (not the genes) in urban environments:

… bird songs are modified in different ways to deal with urban noise and promote signal transmission through noisy environments. Urban noise is composed of low frequencies, thus the observation that songs have a higher minimum frequency in noisy places suggests this is a way of avoiding noise masking. … we experimentally test if house finches (Carpodacus mexicanus) can modulate the minimum frequency of their songs in response to different noise levels. … We conclude that house finches modify their songs in several ways in response to urban noise, thus providing evidence of a short-term acoustic adaptation.2

… We compared the songs of blackbirds, Turdus merula, from the city centre of Vienna and the Vienna Woods and found that forest birds sang at lower frequencies and with longer intervals between songs. This difference in song pitch might reflect an adaptation to urban ambient noise. However, the song divergence could also be the result of more intense vocal interaction in the more densely populated city areas or a side-effect of physiological adaptation to urban habitats. 3

We studied three adjacent dialects of white-crowned sparrow songs over a 30-year time span. Urban noise, which is louder at low frequencies, increased during our study period and therefore should have created a selection pressure for songs with higher frequencies. … We suggest that one mechanism that influences how dialects, and cultural traits in general, are selected and transmitted from one generation to the next is the dialect’s ability to be effectively communicated in the local environment.4

I’m fairly certain that if a similarly structured set of findings were presented for humans, there would be many who would jump in and insist that the change is genetic. Humans have fetishized their own genetic evolution to the point that if something is not considered genetic, then it may as well not be considered biological at all. But people who study birds know better. And, it may simply be the case that our feathered friends demonstrate parallel evolution more clearly than do humans, in part because the learning of song is accompanied by overtly visible neurological changes in the birds, while learning, when it happens in humans, does not. In any event, the songs of song birds focused Darwin’s writing about the evolution of humans “and selection in relation to sex” in 1871, and it tends to focus our thinking these days about the evolution of language and other cognitive facilities in humans.

So next time you hear a human blathering on about the genetics of human behavior, ask them to listen for a minute to the birds chattering outside. Ask if he thinks bird song is a genetically determined behavior. And use that special look you’ve surely developed by now indicating that this is a trick question. One raised eyebrow can be worth a thousand tweets!

__________________________

1Darwin, C. R. 1871. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray. Volume 2. 1st edition. The quoted parts are from page 414. Online here.

2Bermudez-Cuamatzin, E., Rios-Chelen, A., Gil, D., & Garcia, C. (2010). Experimental evidence for real-time song frequency shift in response to urban noise in a passerine bird Biology Letters, 7 (1), 36-38 DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0437

3Nemeth, Erwin and Henrik Brumm. 2009. Blackbirds sing higher-pitched songs in cities: adaptation to habitat acoustics or side-effect of urbanization? Animal Behaviour

Volume 78, Issue 3, September 2009, Pages 637-641.

4Luther, David and Luis Baptista. 2009. Urban noise and the cultural evolution of bird songs. Proc Biol Sci. 2010 February 7; 277(1680): 469–473.

The image of the sonograms is from Lipkind, Dina and Tchernichovski, Ofer. 2011. Quantification of developmental birdsong learning from the subsyllabic scale to cultural evolution. Published online before print March 21, 2011, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012941108 PNAS March 21, 2011.

Great post.

Do you know if any research exists that indicates if individual birds ever change their songs in response to ambient noise? It seems doubtful that it would happen and have been studied but imagine the advantage that such a bird would have…

Thanks for the question. Other than the changes in frequency during learning? It has been argued that bird song generally is a response to ambient noise (natural and, now more recently, human-made); Alejandro Ariel Rios-Chelen of the Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México suggested that different ambient noise might interfere with the functions of bird song to different degrees, resulting in different degrees of selection. Using this idea it may be possible to predict what species might be more likely to have the ability to change as adults in response to noisy backgrounds.

The first thing that comes to mind are the imitating birds. There is a paper on mockingbirds that only talks about them raising their voice, as it were. One time in the Ituri Forest a bird seemed to adjust its song to imitate my watch which I had been using to announce time intervals as part of my research. Messed up my data collection a little, but I’m not sure if it did the bird any good.

Maybe whales do the same thing? In which case they’re learning to sing around propeller noise.

I think one of the most interesting – and basic – points to take away from this is that it is not just genes that respond to selection pressure, but other “non-gene” things as well. Birdsong is one thing, and (I think) memes in humans is another.

Could an evolutionary parallel be drawn between the “overt neurological changes” exhibited by adapting birdsong and human dialects – a southern drawl or a southie accent – within a common language? Or is that too simple a comparison?

Excellent start, Greg! One thing, though: Do you have any citations to studies indicating the ‘atavistic’ nature of territorial singing?

Great story. So if I understand correctly, the birdsong is a meme undergoing Darwinian selection.

I also noted point about selection being for the ability to sing the (presumably established) local variant correctly. Interesting contrast to the song of humpback whales, which changes over a season, with an apparent premium on novelty.

Brent, I don’t think that is too broad of a comparison, though human and bird language/song are very different. The bird “template” is not a chomskian grammar, I assume.

Pete, let me clarify: Male birds in many species have territories and they may perch in those territories and sing. This is a sign of their location, their intent (to defend a territory) and may indicate quality. But both the song and the territory are things that have one main purpose: To be observed, measured somehow, and taken into account by females.

The signals provided by the song are probably in some or many cases effective for both impressing a female and impressing (in a different way) potential territorial rivals. Territory is very much involved in the system.

My reference to identifying bird song as a territorial marker goes to the mid 20th century interest in territoriality and the trend towards forgetting about sexual selection in understanding animal behavior. The territory itself is feature of sexual selection, and individual (male and female, separately) behaviors combine to create an overall ‘strategy’ in which both territory quality, male-male competition, and direct selection of individuals play a role. In this context, the qualities of most bird songs play a major role in mate choice.

One key piece of evidence supporting this generality is that monogamously mated birds that don’t re-mate each season can have a very strong commitment to a territory (during breeding) and don’t use song at all. Eagles come immediately to mind.

This is true, Greg; but then eagles don’t sing to attract mates either. I was thinking more along the lines of passerines, which have songs that are distinct from their various callnotes.

Pete: Exactly. Eagles are more territorial than average for a bird, but their mating system does not use song. These are birds that do territory without song. This does not prove that other birds don’t us, or even need, song to create territories, but it does mean that it is not necessary for birds in general.

See post for discussion of calls/sounds vs. song.

The thing is, there was a time when most signaling, including color and song, in birds, primates, and other creatures, was attributed to a narrow range of functions such as “species identification” or ‘defending’ territory by the basic function of telling con-specifics that you exist and are there. The big revolution with behavioral biology was to attribute a different meaning to the visual and auditory signals. Singing is costly behavior that indicates quality, and that quality indication is primarily for females to use in choosing mates. Territorial marking and species identification may not even happen because the former is unnecessary because that function free-rides on the sexual choice signal, and the later because it is probably rarely needed by any species ever, though it still persists in some of the literature and discussion.

Paul: Actually, the word “meme” is used in bird song evolutionary biology with a straight face, possibly because it actually, really, does work that way. I almost wrote a paragraph or two on that but realized I have 12 more of these posts to do over the next years and needed to save something back!

We had some Zebra Finches who were fostered by a Society Finch. Remarkably, corruption of song was a nice birth control method, because the girls did not dig that Society influence at all. I did not upload the follow-up sonogram, but nearly a year later, the fostered Zebra Finch lost some of the trilling Society-like features from his song.

By the way, for those who have not heard it yet, there is an awesome archive of Zebra Finch songs (click on Family Tree).

Greg, have there been any studies where they have taken (for instance) a starling from the west coast, either to the east coast or to England to see if its language has changed enough over the years of separation to affect its ability to attract a mate?

Are there female birds that sing?

There are females that sing, and there are birds that do duets between males and females. That would be a good future blog post.

Gwen, I don’ know of that exact experiment. It would have to be done in the lab to avoid violating multiple state and federal laws against transport of wildlife. But it would be interesting.

@gwen, there was some study of White-Crowned Sparrows sampled from different “neighbourhoods” of Marin County in Northern California. There was another in which it was demonstrated that those who sang a foreign dialect were less successful than the native-singers at attracting mates. Even some, who live on the border between two neighbourhoods, are “bi-canticular.”

@claudia, above-mentioned is one such species of songbird of which females can sing, but let us stay tuned for future post!

@Greg Laden, I think that European Starlings are exempted from many wildlife laws (at least, they are not protected under MBTA).

Thanks Sara!

Sara, good examples. Regarding moving the birds: It’s not about protection of the birds but rather about moving animals. In Minnesota, unless you are a) carrying a permit or b) under 13 years old (strangely enough) you can’t move a wild animal anywhere. If you are a kid you can capture wild animals and keep them in your house (this is mean to cover snails and little fish, frogs, etc) though there are lots of protected animals, protected even from 11 year olds. I don’t think it is legal, or safe, to move a bird across the country, ever, unless you are the feds. You might do the bird equivalent of what those guys who moved an Arizona-caught raccoon to Arkansas a few year back, starting one of the more impressive rabies epidemics (among raccoon) ever!

Lots and lots of experiments have done testing the reaction one gets when messing with the bird song, including dialect differences, just not at that scale of space that I know of. The article that is mentioned at the very end of the post (where the sonogram comes from) reviews a lot of that research.

I can see how moving birds across the country could introduce a zoodemic(sp?). Here is an article about these risks: http://www.fao.org/DOCREP/004/X2096E/X2096E01.htm I suppose recorded bird calls might give some hint of how successful they might be in attracting females of the species. I love how some urban birds have incorporated common urban sounds into their courting repertoire. I saw one bird (on youtube) alternate between a leafblower and car alarm horn. Another example of how we are impacting the wildlife around us. I hope it helped his cause.

I heard he had a great time with the leaf blower but the car alarm horn was actually seeing someone else and there was a big scene.

LOL! That will teach me to write more precisely!

a note -hmm- on birds responding to other sounds. Just for fun here’s one for you. Aside from learning and call and answer with crows and their wide vocabulary; I also play a variety of flutes.

Cardinals will respond to my flute – more that a few times – a cardinal will sing a string of notes; I repeat these on the flute – the cardinal will sing back and add a note – I have done this for close to; my guess half an hour at a time. The cardinal usually wins; that is; I can’t remember all the notes; and if I mess one up; the cardinal will go back to the ‘tune’ that we started with.

Great post. I remember reading a while back about the plasticity of birdsong and of the neural circuitry of birds. I was really surprised that new neurons are formed in these birds during adulthood as they learn their songs. Do you know if the birds that are raised in captivity and “taught” incorrect songs are able to correctly learn their song if they are later exposed to it as adults?

Yes, in at least some song birds, the seasonal learning is essentially independent. After a year of suffering through the mad scientist’s messing with your head, you can go back to learning the normal song if they didn’t take your brain out or anything like that.

What’s really cool about this is (at least in my opinion, this is not verified to my knowledge): birds actually grow brain tissue to do all this singing, then resorb it later. This makes sense since neurons are very costly tissue, and birds live, in a sense, on the edge of their energetic budgets, more so than many other vertebrates.

@Greg Laden, I know that a professor on my campus who works with live Starlings is not required to possess a Scientific Collection Permit, but he does not transport them. Meanwhile, I must have a scientific collection permit for feathers but only of migratory birds. Also, some people keep Starlings as pets. If some such Starling custodian moves from one state to another, even if this is violation of Lacey Act (or something else), I do not know how it would be overseen (although, risk of disease propagation is low if the bird does not escape). I agree that precautions should be taken but have little faith that even the feds could pull it off :/ Nevertheless, I do not think that the extra-laboratorial experiment is worth the risk.

Is the age limit of the Minnesota law intended as a permission for children to play with frogs and catch fireflies?

@Eriana, I had similar experiences with Northern Cardinals while practicing outside on flute. And there is an occasional whistle-war with Mockingbirds (I always lose!).

Female birds that sing are mostly found in the arid subtropical deserts and semi-deserts of Australia and Africa. In fact, in these regions of exceedingly infertile soils and unpredictable food availability the vast majority of female birds sing just as males do. This is because both sexes must be brought into breeding condition by song when adequate rains fall and food exists, and because many species need large numbers of beaks to fledge even a single chick (obligate cooperative breeding) which creates communal song to defend against threats. (Interestingly, human music originated in a manner similar to such birds as butcherbirds, fairywrens and sparrow-weavers).

Whilst some “rabid feminists” seem by the fact that only male birds sing in the Enriched World where strong and reliable seasonality makes study vastly easier, if one considers a few basic facts it makes sense that complex song in these young, fertile environments should disappear from females.

Pair-bonding is very short in the highly seasonal climates of Eurasia, North America, extratropical South America and New Zealand. The superabundant spring food supply means one adult can feed young – whereas up to five may be required for possible success in Australia and Southern Africa! As a result, males can compete much more intensely for females than when the care of many of them is essential for breeding success. Also, female singing in the Enriched World may be disfavoured by low sound attenuation and high densities of mammalian predators, which means females are more vulnerable than in low-fertility Australia and Africa.