Tim Birkhead loves to tell stories. They may be about bird eggs (The Most Perfect Thing: The Inside (and Outside) of a Bird’s Egg, 2016), or a 17th-century ornithologist (Virtuoso by Nature: The Scientific Worlds of Francis Willughby, 2016), or How Bullfinches learn songs from humans (The Wisdom of Birds: An Illustrated History of Ornithology. 2008 and this video recommended by the Ted Talk people: The Early Birdwatchers), or the social behavior of Common Guillemots (what we North Americans call Common Murres) (Bird Sense: What it Is Like to Be a Bird, 2012). Stories enhance his 2014 history of modern ornithology, Ten Thousand Birds (co-written with Jo Wimpenny and Bob Montgomerie). And they are key to his latest title, Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History from Cave Art to Conservation, a buoyant, bustling history of scientific ideas combined with snapshots of eccentric personalities, ornithological anecdotes unearthed from the pages of old journals, and personal recollections. The book is chiefly about how people have conceptualized and studied birds, but there is an underlying theme, the changing ways in which our Western culture has viewed animals, nature and God. It’s a huge scope for a 338-page book. Birkhead, the experienced storyteller who is also Emeritus Professor at the School of Biosciences, The University of Sheffield, author of multiple scientific articles as well as books of popular science, knows how to make it readable and fun.

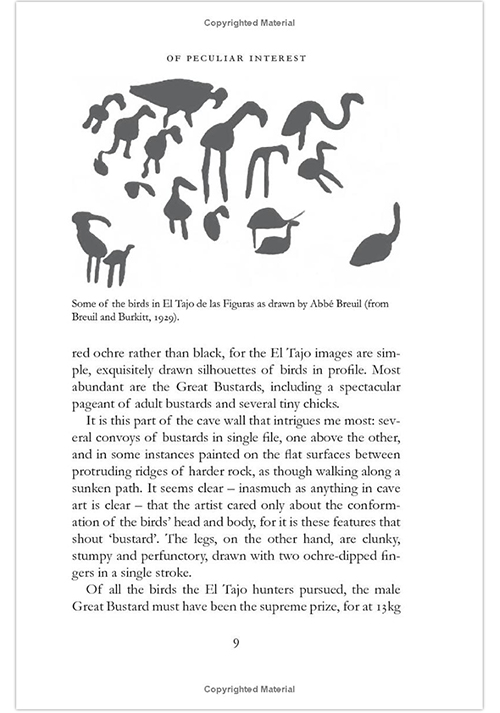

Birds and Us starts with Birkhead’s visit to Cueva del Tajo de las Figuras, located in Andalusia, Spain and the Neolithic bird paintings on its walls. This is “the deep cradle of Western ornithology: the birthplace of bird study,” he tells us as he writes about gazing at the 8,000-year old depictions of “flamingos, herons, raptors, avocets and many other species” (p. 1). Birkhead recounts the story of how the cave was discovered (sort of, it was previously known to the local people who told him about it) in the early 20th-century by Colonel William Willoughby Verner; gives a mini-biography of William Verner, British soldier, bird photographer, and inventor; then goes back to the cave’s discovery and documentation by Verner and another personality, Abbé Henri Breuil (it’s complicated); summarizes academics’ efforts to identify the 208 birds on the cave walls; and then engages in larger scope discussion about why the paintings were created and how proposed explanations have changed over the years: totemism? sympathetic magic? shamanism? Or, as Birkhead half seriously, half whimsically suggests, a field guide? The chapter is a dizzying, though always entertaining, narrative progression from the personal to the historical to the analytic and then back again, representative of the 11 additional chapters that follow.

Some of the cave paintings of El Tajo de las Figuras taken from H. Breuil and M. C. Burkitt, Rock Paintings of Southern Andalusia, 1929. Text © 2022 by Tim Birkhead

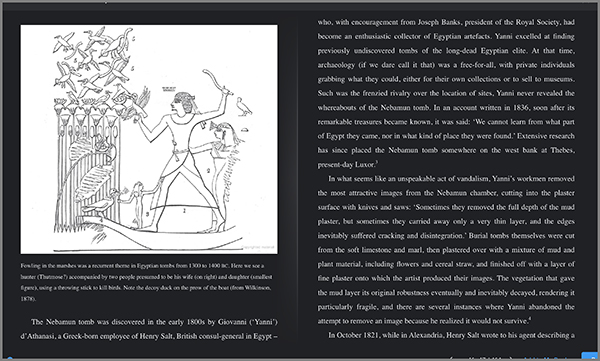

Each of the 12 chapters focuses on a chronological era and sometimes a place, through the details within often jump around in time and space, echoing Birkhead’s personal and scientific associations with the topic. There’s the Neolithic era; Ancient Egypt (bird mummies!); Ancient Greece and Rome (Aristotle liked birds, as did Pliny and Plutarch); Medieval times (mostly falconry); the Renaissance (dissection and anatomical studies, the first appearance of Neotropical birds in European ornithological works); the groundbreaking classification work of Francis Willughby and John Ray in the late Renaissance; the seabirds of the Faroe Islands (an essay on the interaction between puffins, murres, fulmars and the people who kill and eat them, a delicate balance first observed by a Danish priest in the mid-17th-century); the 19th-century ideological explosion that followed the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species (appropriately titled “The End of God in Birds”); the Victorian Era’s obsession with the collecting of bird skins and eggs (leading to the development of museum collections and eventually, today, to the controversy about shooting and collecting of specimens–remember, I did say there are jumps in time); the emergence of a new relationship with birds in 20th century Great Britain (birdwatching!); the development of field-based ornithological research in Europe and Great Britain; a quick step back through the history to look at bird protection, conservation, and our precarious future, with a focus on Birkhead’s long-term (50 years!) Common Guillemot research at Skomer Island, Wales.

Birkhead focuses on those stories that both illustrate each chapter’s theme and clearly have meaning to him, and though the Birds and Us of the title primarily refers to how we, humans, observe and value birds, there are forays into birds and art, literature, medicine, food, religion, and biography. His musings on falconry in Medieval times begin with the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the Norman Conquest and is full of birds, including hawks and falcons on the wrists of the main contenders. He continues with images found in illuminated manuscripts such as Catherine of Cleves’s Book of Hours and Frederick II of Germany’s On the Art of Hunting With Birds. And interspersed with these artworks is one of the more curious digressions in the book, the life of William Brunsdon Yapp, a 20th-century British ornithologist who studied medieval iconography in retirement. Birkhead rightly credits Yapp and his obsessive research for a lot of what we know about medieval falconry, but it’s not clear why he needs to describe the scholar’s notorious curmudgeonly personality or his sad old age. It’s at moments like these that I felt like I was listening to a podcast or one of Birkhead’s popular lectures rather than reading a history book. There’s an intimacy to these stories, the memories connected to the telling of the histories, that’s appealing and a bit surprising. With Birkhead, you never know what’s going to come next.

Egyptian tomb painting depicting duck hunting in the marshes, from the eBook version of Birds and Us, © 2022, Tim Birkhead and Princeton University Press.

There are two subjects which I think could have been explored more thoroughly–women in ornithological history and colonialism. Birkhead knows that these are sensitive topics. He writes: “In nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe, North America and Australia, a serious interest in bird was predominantly a white, wealthy, middle- or upper-class and often-colonial male preserve….The start of birdwatching in the early 1900s…–with some notable exceptions–was still pursued principally by men” (pp. 266-67). He scatters mentions of female naturalists and artists throughout the book, but almost always it’s simply a mention. One exception is Magdalena Heinroth, a German ornithologist who, with her husband Oscar, raised and studied thousands of birds in her apartment in pre-World War II Berlin. Magdalena’s story seems to appeal to Birkhead for two reasons: his fondness for raising birds in the home, something he did as a boy, and the Heinroth’s pioneering work in the study of bird behavior, his own scientific specialty. Other women do not seem to have captured his attention. Florence Merriam Bailey is quoted in the beginning of Chapter 10, the chapter on the emergence of birdwatching. Yet Birkhead credits British ornithologist Edmund Selous with sparking the world’s interest in watching rather than killing birds, despite the fact that Bailey’s “interest in bird-watching predates his,” as he admits in a footnote (p. 374). The difference seems to be that Selous had previously killed birds and she had not. I do not understand why this should take away from the American woman’s achievement.

Birkhead also misses the perfect opportunity to talk about one of the most undervalued women in ornithological history, Elizabeth Gould. The wife of taxidermist, naturalist, and author John Gould, Elizabeth painted, designed, and lithographed over 650 bird illustrations which appeared in John’s famous ornithological works and, uncredited, in Darwin’s The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, pt. III. Birds. Although historically Elizabeth has been credited with creating lithographs based on others’ drawings (her husband’s), there is research indicating that she was actually the artist who drew and colored the original images. Birkhead talks about John Gould in several contexts, including a portrait of him and his family and his bird skins by John Everett Millais, reproduced in the color plates section, the only mention of Elizabeth is her co-authorship with John Gould, of another color plate, ‘Comb-crested Jacana.’ Ironically, this is from Birds of Australia, which scholars and art historians suspect was more Elizabeth’s work than John’s.*

Colonialism and appropriation of knowledge is discussed in Chapter 6, The New World of Science. This is the chapter about the 16th- and 17th-centuries, when information about the birds of the ‘New World’–what they looked like and the use people of the New Worlds made of them–was making its way to England (and to Willughby and Ray, who were writing their taxonomy of all the birds of the world) via a long, complicated route involving naturalists’ observations filtered through political patrons, censored by religious ideology. Yet the knowledge always began with what the European explorer/naturalist saw and was told by the country’s indigenous peoples, And it always ended with no credit being given to these people. Birkhead acknowledges the view of historians like Nancy Jacobs, who criticizes European/Western ornithologists for exploiting their indigenous assistants and informants and stripping away original meaning from indigenous practices and knowledge bases (Jacobs writes about Africa, but her critique is easily applied to any place where colonialism occurs). But he also defends those ornithologists, saying that the British and European people he’s writing about really did value their assistants, and reducing the otherness of colonialism to an issue of giving appropriate credit.

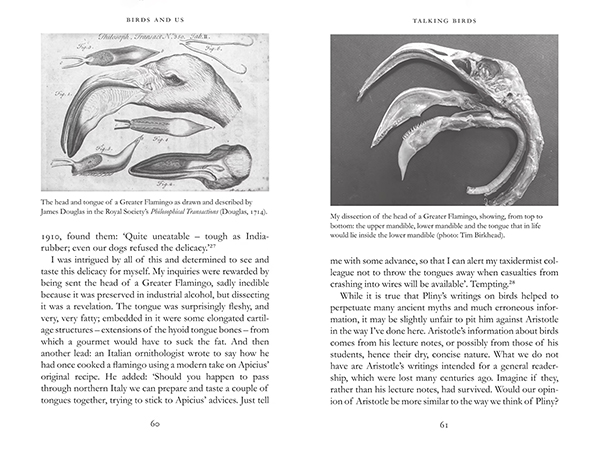

A book about the study of birds cries out for illustrations, and Birds and Us offers quite a lot–color plates in a separate section and black-and-white illustrations integrated in the text. The 32-page insert of color plates presents 63 images of paintings, book plates, mosaics, photographs, and a map, culled from Wikipedia Commons and other sources. The images tie directly to the text. We see the reddish El Tajo cave paintings, Sacred Ibises carved on Egyptian tombs, closeups of the Bayeux Tapestry (interestingly, five of the 32 plate pages contain falconry images), tiny paintings of birds from Brazil commissioned by Count Johan Maurits in the 1600s, photographs of the Heinroths and their home-raised birds, John James Audubon’s painting of the now extinct Guadalupe Caracara (one of Audubon’s only appearances in the book), and Birkhead’s own photographs from his travels to Andalusia and Peru and his research at Skomer Island. The plates are listed in the front of the book, but are not referred to in the text or the index, which means they exist in a partial vacuum; you need to really study that listing to know that they’re there when you’re reading a relevant part of the book. The 70 black-and-white illustrations are much more helpful since you see them as you read about them. They are also included in the index. A nice example of their usefulness are these contrasting illustrations of the head tongue of the Great Flamingo, which Birkhead writes about as an anatomical curiosity and a reputed culinary delicacy. The drawing on the left is from 1714, the one on the right is the result of Birkhead’s own dissection.

Great Flamingo tongues & heads: p. 60, drawn and described by James Douglas, Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, 1714; p. 61: dissection showing upper mandible, lower mandible, and tongue, photo by Tim Birkhead, © Tim Birkhead; text © 2022, Tim Birkhead and Princeton University Press.

Great Flamingo tongues & heads: p. 60, drawn and described by James Douglas, Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, 1714; p. 61: dissection showing upper mandible, lower mandible, and tongue, photo by Tim Birkhead, © Tim Birkhead; text © 2022, Tim Birkhead and Princeton University Press.

There is extensive back-of-the-book material: a “List of Birds Mentioned in the Text,” Acknowledgements, Notes, Bibliography, and Index. The listing of birds in the text (common and scientific names and cross-references) is a puzzle. These birds (and their cross-references) are also included in the index and this separate listing does not include page numbers or any additional information. The Notes are on the other hand well-worth reading, including documentation of the text and additional comments, even more stories, by Birkhead. I found myself doing a lot of flipping around while I read Birds and Us, going from text to notes to bibliography to notes to text and back again. I haven’t had a look at any of the eBook formats, hopefully they include links to make this easier. The Bibliography is extensive (I wouldn’t expect anything less), 28 pages of articles and books in English, German, and Latin ranging in date from the 16th-century to 2021. The Index lists names, places, birds (by complete common name), and most of the book’s subjects (conservation, cruelty, extinction, morality, but ‘god’ is limited to animal gods).

Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History from Cave Art to Conservation is a fascinating, informative, sometimes frustrating, idiosyncratic history of the observation and study of birds from a Western cultural perspective. It’s content is very different from a similarly named book, also by a well-known British nature writer, Birds and People by Mark Cocker. Birds and People is encyclopedic and dense with facts, covering all aspects of the artistic and cultural places where birds and human beings intersect. Birds and Us travels through time and space, mostly a British and European space, at a meandering pace, stopping at unexpected times and places to tell the stories of the people who observed and thought about birds and the values and ideologies they brought to their observations; also stopping occasionally to take a holistic view of the interdependence of birds and people, how a system like the use of birds for food in the remote Faroe Islands is no longer sustainable. Birds and Us is a book that prompts us to think about big ideas through stories. The stories are true, I wish there were more stories about women and people from outside Great Britain and Europe, but they are good stories and I highly recommend you read them.

* Ashley, Melissa, “Elizabeth Gould, zoological artist 1840-1848: Unsettling critical depictions of John Gould’s ‘laborious assistant’ and ‘devoted wife’,” Hecate, No. 1/2, 2014: 101-122, accessed via Academic Search Premier, 08/26/22; and Wetzel, Corryn, “Meet Elizabeth Gould, the Gifted Artist Behind Her Husband’s Famous Bird Books,” Audubon Magazine, May 14, 2021, https://www.audubon.org/news/meet-elizabeth-gould-gifted-artist-behind-her-husbands-famous-bird-books.

Birds and Us: A 12,000-Year History from Cave Art to Conservation

by Tim Birkhead

Size: 6.13 x 9.25 in.; Illus: 63 color + 70 b/w illus. 2 maps.

Princeton Univ. Press, August 2022, 496pp., $35.00

Hardcover: ISBN: 9780691239927

ebook, ISBN: 9780691239941

Audio: ISBN: 9780691243788

British edition: Viking Press (Penguin), March 2022, ISBN: 9780241460498, £13.00

Leave a Comment