Here are some of the things I learned reading Birds in Winter:

- Birds who store food in advance of winter (corvids, tits, and nuthatches) have a larger hippocampus (the brain structure that regulates memory) than non-storing birds do.

- American Avocet, Black-bellied and Semipalmated Plovers feed nocturnally during winter, the same number of hours as they feed during the day; smaller shorebirds feed more at night.

- Harris’s Sparrows denote dominance by the amount of black on the head, the adult male birds with the most black ranking highest. This visual marking of who’s in charge (and who’s not) helps reduce aggressive actions within the flock during winter, so the sparrows’ energy can be used more productively for finding food and watching out for predators.

- Skiers and snowboarders in the Swiss Alps who explore on their own contribute to the winter stress of Black Grouse by flushing them in the middle of the day, exposing them to predators and causing them to use up energy stores; proof was found in a study that analyzed the birds’ fecal matter and found high levels of corticosterone, a stress hormone.

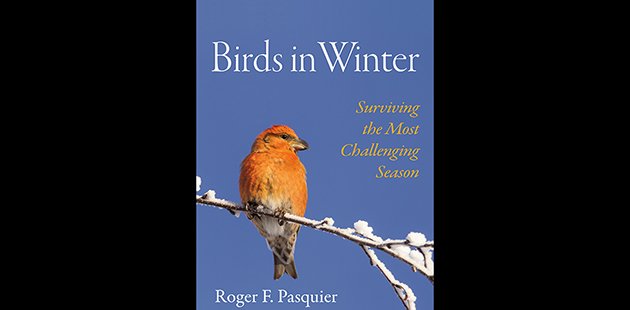

There’s more, so much more, in this highly informative, detail-packed, research-based description of bird behavior. Author Roger F. Pasquier has set himself a formidable challenge in Birds in Winter: Surviving the Most Challenging Season. He aims to bring together all ornithological and ecological research on birds and winter the world over–not just in areas covered by snow–and summarize the findings in non-scientific language. This includes current research (up to about 2016, but mostly earlier) on how climate change and human change are affecting the birds’ ecology and behavior. The book offers numerous facts about many species, findings of hundreds of research projects, notes on trends and exceptions from the norm, but little that captures the poetry of winter bird behavior or ignites a passion for change.

Page 53, Illustration by Margaret La Farge, used by permission of Princeton University Press, https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691178554/birds-in-winter

The book is organized logically by seasonality. An introductory chapter describes how migration evolved in response to winter hardships, different types of migration, and how scientists use technology to study migration. We are then taken through what birds do before, during, and after the winter months, chapter by chapter: how the prepare for winter (molt sequences, food hoarding as early as summertime, triggers for departure); migratory ranges and habitat selection (habitat partitioning, site fidelity, migratory connectivity); social organization and territoriality (flocking, dominance, interactions with resident species); survival techniques (diet shifts, predation, dealing with the cold); optimizing “The Winter Day” (when to feed, roost, and sleep, roosting alone or in flocks); getting ready for spring (winter pairing, winter breeding, effects of winter experience on spring and summer breeding); and “Departure’ (when to leave, how to leave, differential timetables). Two sobering chapters on “Conservation” and “Climate Change” end the text section of the book, followed by a 36-page Bibliography and a detailed Index.

The seasonal life of one bird species is complex; life cycle events like aging, breeding, molt, and migration are intricately tied to habitat, food availability, genetic ‘instincts,’ hours of daylight, and weather. These complexities multiply when describing the winter (and pre-winter and post-winter) lives of more than one, in this case, any and all species that have been studied for their migratory, winter feeding and protective movements, or any related behavior. Pasquier cites study after study, often jumping from one continent to another, from one bird family to a totally different group, relying on a bibliography of over 660 studies to lay out the variable, diverse behaviors birds employ. For example, in the section on the advantages of single-species flocking behavior, we learn about Eurasian Hazel Grouse in Sweden and Siberia, then Black-capped Chickadees in Ithaca, New York, and then Eastern Kingbirds in Peru and Panama. The effect can be overwhelming, and I found myself reading some sections two, even three times, to understand it all. This is, of course, because research itself is specific, and developing generalizations from ornithological specificity is tough. There are too many buts, excepts, and maybe’s, a lot of research on some species and very little on others. Still, I liked the idea that all of these studies, many seemingly disparate, have been brought together to form one body of knowledge.

Birds in Winter often reads more like a textbook than as an engaging discussion of bird life, but it is a book that fills a huge whole in the popular literature. I found myself thinking of Birds in Winter earlier this week, as I searched Willow Lake, a marshy, under-birded area near my home, for two elusive overwintering warblers, an Orange-crowned and a Nashville: food must be scarce and there’s little cover from predators, so those birds were covering a wide area, low to the ground, and understandably very skittish, they might not be where they were seen the day before. The thinking didn’t help me locate the warblers–Willow Lake has few trails and many were under water–but they did help me understand why I was not finding them.

The text is helpful on a more serious scale when it comes to considering conservation and climate change. These are the most important chapters in the book, in my opinion. Having established interrelationships amongst habitat, weather, food sources, water sources, migration, and hours of daylight, Pasquier then brings in the conflicts and mismatches that occur when one or more of these elements change. Much of this will be familiar to the informed birder: warblers wintering in the Neotropics are losing habitat to forests being converted to farms, but shade coffee plantations provide comparable habitat while sun coffee plantations and silvopastures (tree farms) don’t. Warming temperatures have resulted in gradual range shifts of resident and migratory birds and new migratory timetables. Long-distance migrants, whose migration times are set by changes in day length, arrive at their breeding grounds only to find that the plants or insects they rely on are gone or eaten by resident species. But a lot will be new, particularly the many studies that prove these are real changes supported by hard data.

A lot of thought and attention has clearly gone into the book design, and I think it adds immensely to the text’s readability, relieving some of its density. Headings and subheadings of varying sized fonts and dividers adeptly guide the reader through each topic and subtopic. And, the delicate drawings by Margaret La Farge illustrate selected points, providing both a visual counterpart to the research summaries and, more importantly, a sense of grace and wonder. There are 73 illustrations and 6 maps (I counted), though the publicity material lists 85 illustrations and 4 maps.

Page 169, Illustration by Margaret La Farge, used by permission of Princeton University Press, https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691178554/birds-in-winter

Author Roger F. Pasquier, currently an associate in the Department of Ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History, has had a long career involving ornithology and art history (and apparently, picking up coins, bills and Metro cards from the streets of Manhattan, according to an article in The New Yorker). He’s written books on birds and art (Painting Central Park with co-author Amanda M. Burden, 2015 and Masterpieces of Bird Art: 700 Years of Ornithological Illustration, 1991) and an introduction to ornithology (Watching Birds, 1977), and has been associated with the International Council for Bird Conservation, Environmental Defense Fund, and the National Audubon Society. He writes in his Introduction that writing this book, about bird behavior during winter, has been a dream since 1976, and charmingly talks about how much fun he had researching and writing Birds in Winter at the library of the American Museum of Natural History. I wish some of that sense of fun and personal involvement had been carried over to the text itself.

Birds in Winter: Surviving the Most Challenging Season treats avian survival processes in a unique way, focusing on winter, a time of year under increased scrutiny from scientists and policy makers. The uniqueness of the topic is modified by the textbook-like writing style. We get the facts, but, unlike research-based writings of other authors (Kenn Kaufman and Scott Weidensaul come to mind), we don’t get a sense of beauty or wonderment. So, this is a book to read if you want the information. You can then take those facts out into the snow (or, if you live in NYC, the sunshine under which the bushes are starting to bloom), and use the larger context to enhance your birding experience. And, bring a more informed view to discussions, referendums, and practices involving conservation and climate change. Because, whether our future winters are warmer or colder, we want to survive them with our birds.

Birds in Winter: Surviving the Most Challenging Season

Written by Roger F. Pasquier, Illustrated by Margaret La Farge

Princeton University Press, 2019

304 pages.

ISBN-10: 0691178550; ISBN-13: 978-0691178554

Price: $29.95; Kindle: $19.42

Leave a Comment