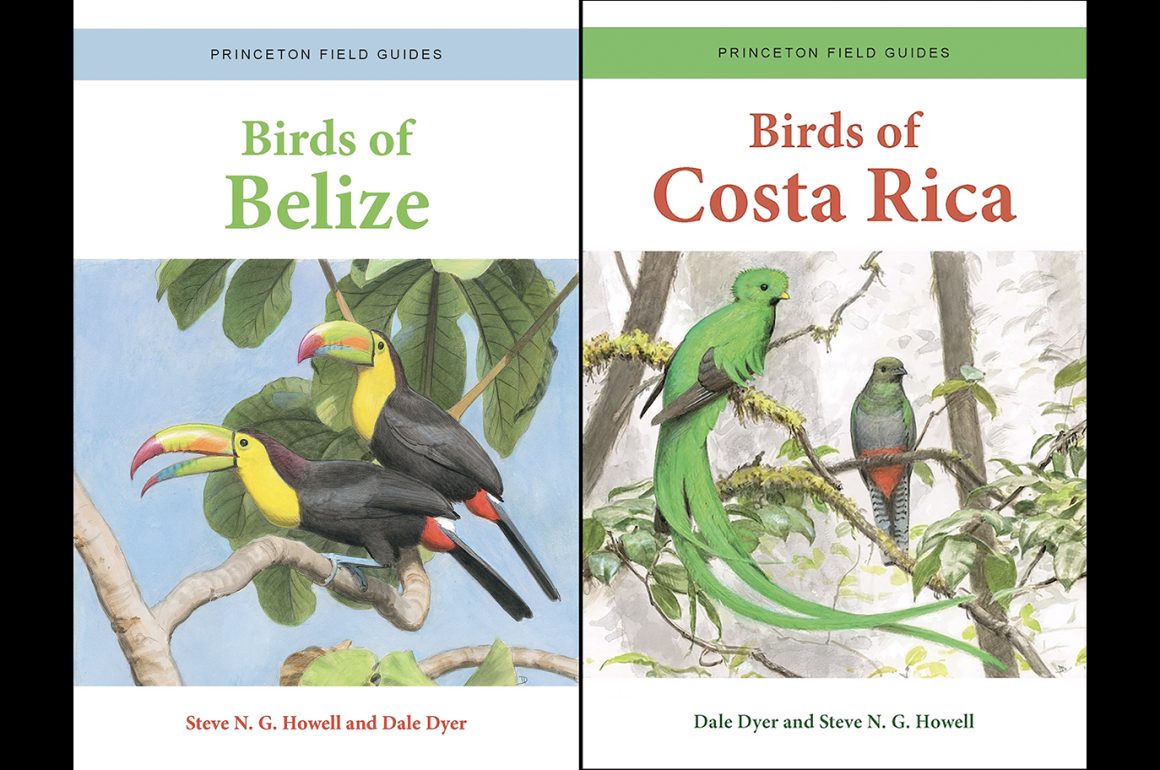

Two books, two authors, two countries bursting with neotropical avian diversity. Birds of Belize by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer and Birds of Costa Rica by Dale Dyer and Steve N. G. Howell joined the field guide roster this spring, very welcome in a year sadly sparse in new titles. Since the books share authors and a creation process, I thought I would review them together. Both titles are superlative guides to two popular birding destinations, featuring detailed yet succinct up-to-date descriptions, magical scientific illustrations, and the well-crafted organizational features by now expected from Howell, one of our most prolific bird book writers and a vocal proponent of user-friendly guides. Yet they also bring up questions, which I’m going to talk about right now before diving into the specifics of the guides themselves.

Two issues came to mind immediately when I examined my reviewer copies. The first is that the illustrations by Dale Dyer are based, and largely seem to be the same, as the illustrations for his previous guide Birds of Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama (co-authored with Andrew Vallely, PUP, 2018). It’s not clear how many of the plates have been touched up, redrawn or are new, and I hope we’ll learn more about the process, perhaps when the third book in the series by Howell and Dyer, a new guide to the birds of Mexico, is published.* An associated issue is that the Belize and Costa Rica guides share many of the same descriptions of species, written by Howell.

Why are these issues? I think because we, or at least I, have a fantasy of every field guide being created unique and new, that when I gently lift the cover a new guide, I’ll find treasures we’ve never seen before. Fantasy is the key word here. If we want new field guides, we need to admit that it’s not economically or humanly possible to draw and paint a new Clay-colored Thrush for each title. Doing this work takes time! Dale Dyer put in years working on his paintings for Birds of Central America, both in the field and in the museum. I don’t think scientific artwork holds less value when used more than once. Similarly, descriptions of species repeated across volumes do not lose their accuracy with each publication. Steve Howell has spent decades of experience in the field studying the birds of Belize, Costa Rica, and especially Mexico. There is no reason expertise and talent cannot be shared across field guides when the books are published close together, like these are. I think we do have the right to expect that artwork and species descriptions when repeated are current, reflect recent studies and taxonomic thought. And I think these guides do, that the authors are not just rubber-stamping their work but have sought to make sure the artwork and text in each guide represents the birds of each country.

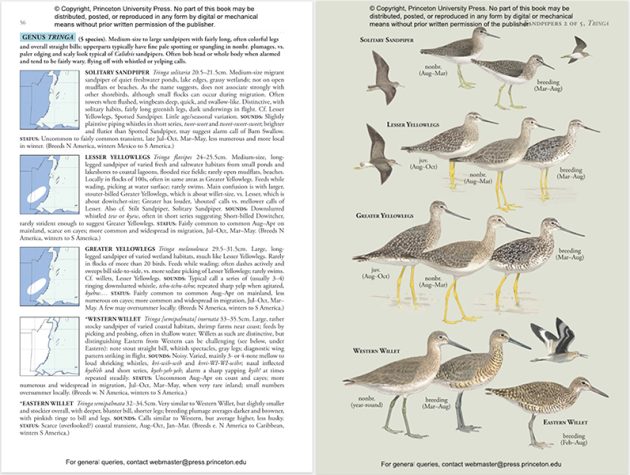

© 2023 by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer, Birds of Belize, “Genus Tringa, page 56, from Princeton University webpage, https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691220727/birds-of-belize

The second issue involves taxonomy. Howell utilizes the IOC World Bird List (v.11.2, 2021) as his “baseline taxonomy” and then makes changes, lots of changes. For oceanic birds he uses the taxonomy that he and Kirk Zufelt developed in Oceanic Birds of the World: A Photo Guide (PUP, 2019). Other species are splits and lumped and have had their names changed. Not every bird. Most of the names here will be familiar to the experienced Neotropical birder. But Howell has strong feelings about what makes a species and what evidence supports splitting or lumping a species and he applies them, in some cases coining his own common names. Tropical Kingbird is “Middle American Kingbird,” based on the idea that good ol’ TK should be divided into three species based on song, morphology, and plumage. Southern Lapwing is “Cayenne Lapwing,” split from “Chilean Lapwing.” Willet is listed as “Western Willet” and “Eastern Willet,” two separate species, something we’ve expected from the North American Classification Committee for many years, but which has not yet passed committee muster. American Herring Gull is “Smithsonian Gull,” a separate species from its European counterpart. And Sandwich Tern is Sandwich Tern, Howell finding the DNA research for splitting it “weak.” These are just some examples. The introductory section “Taxonomy” summarizes the authors’ approach to this process in both guides and lengthy appendix sections entitled “Taxonomic Notes,” explain specific species changes.

Why is this an issue? Taxonomy and classification systems for any area of knowledge, not just ornithology, are traditionally developed, written, and approved by committees and networks of experts with degrees and titles of authority. I should know, as a librarian I was taught to worship classification systems like LCC, the Library of Congress Classification system which divides knowledge into 21 basic classes, and subject heading authority lists. In birding, we have several higher authorities–the AOS Checklist of North and Middle American Birds; the AOS Checklist of South American Birds; the Clements classification system, which is the basis for eBird; the IOC World Bird List; and the checklist developed by Handbook of the Birds of the World and Birdlife International. And when writing a field guide, it is accepted practice to adopt one of the above and to stick to it, with any questions or disagreements safely ensconced in the text, not in an actual change of species.

Howell turns all that on its head. The concept of species, he states, “basically comes down to a matter of opinion, with no right or wrong” (CR guide, p. 30). And as for who has the authority to make taxonomic decisions, he and Dyer argue in their related article in North American Birds, “Costa Rica: Even Richer Than we Thought?”(a must-read for birders who will be using these guides and who want to know more about their development) that “persons who study a region and are familiar with its birds are often better placed to make informed taxonomic decisions than remote bodies dealing with much larger geographic areas.”** Howell also states that there is no better place than a field guide in which to introduce taxonomic changes, something he’s been doing since he and Sophie Webb wrote their guide to Mexico and Northern Central America in the 1990’s.*** It’s faster than committee work, more direct than bureaucracy, and it presents a clearer and more complete portrait of the range and value of the biodiversity of these countries. “We hope that drawing attention to them [the splits] acts as a laxative on the taxonomic constipation manifested by some committees and speeds the rate at which ignorance and inertia fall victim to reality” (CR guide, p. 30).

These are convincing, smartly presented arguments. But I can’t help thinking about the individual birder using these field guides, especially a birder new to Neotropical birding. I think it’s confusing to see Middle American Kingbird in the field guide but not in eBird. I don’t think it’s helpful to have Herring Gull presented as “Smithsonian (American Herring) Gull.” I don’t think every birder wants to take the time to read taxonomic notes and think about the 100-plus splits proposed by Howell and Dyer. (I’m not saying this is right, I’m saying, as someone experienced in using reference books with people seeking a specific answer, there is a limit in how much preparatory time they’re willing to put in.) In presenting a field guide with alternative taxonomy and names, the authors may be jumpstarting “official” changes in taxonomies and birding checklists, but they may also be incorporating obstacles in these books; field guides are supposed to be making birding and bird identification easier, not more confusing.

I don’t think this is a black-and-white issue and I’m hoping readers of this review have their own opinions that they will articulate here or on ‘the socials.’ And perhaps another 10,000 Birds reviewer will have a different point of view.

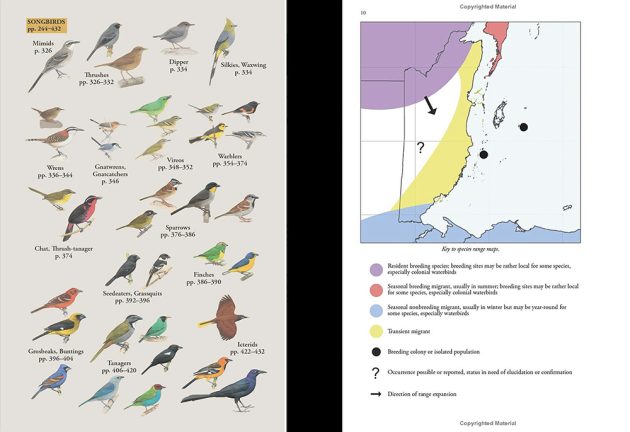

Examples of two types of informational aids offered in both guides: Pictorial Contents for Songbirds (Birds of Costa Rica) and Key to Species Range Maps (Birds of Belize). Birds of Costa © 2023 by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer and Birds of Belize © 2023 by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer.

Coverage & Organization

Birds of Belize covers 540 or so species (I counted, the press release says “over 500”) regularly found in Belize, including the islands of the barrier reef and marine waters about 30 miles out, the range of a day trip. In addition to species regularly occurring in Belize, migrant and resident, the Species Accounts section also includes several rarer occurring species. Some, like American Bittern, are allotted full accounts; others, like White-faced Ibis, are cited and drawn to distinguish them from similar-looking species (in some cases, as with White-faced Ibis, there is a possibility that they may have been overlooked). Appendix A lists “Rare Migrants and Vagrants,” 81 species, including birds for which there are no documented records, but which are listed in the literature or eBird. For context, the IOC version 13.1 Checklist for Belize lists 622 species in 76 families, of which 104 are rare or accidental and four introduced.

Birds of Costa Rica covers 836 regularly occurring and some rarer species found on the mainland, inshore islands, and waters about 30 miles out. “Offshore Visitors, Rare Migrants, and Vagrants,” 103 species including several seabird species, are listed in Appendix B. The birds of Cocos Island, an isolated, volcanic island with a rich bird life, are listed in another Appendix section. This is impressive coverage of a country that boasts over 950 avian species (the IOC version 13.1 Checklist lists 955 species in 86 families, with 152 rare/accidental species, three extirpated species, five introduced species, and nine endemics).

The books are flexibound, with front and back flaps. The front flaps offer handy keys to the species range maps (see image above), the back flaps offer all–too-brief bios of the authors (I want more!). The inside front covers are the start of four-page pictorial guides to bird families/groups and the pages where they can be found, a quick, easy entry to the identification process (see image above). I particularly like the way some bird families, like Antbirds and Tanagers, show groupings of several different species, representing the variety of shapes and colors found in that family.

Front of the book material consists of: “Preface and Acknowledgements,” useful for its summary of the authors’ backgrounds in Belize and Costa Rica as well as acknowledgement of previous works; a succinct guide on “How To Use This Book” (please read!); three drawings illustrating “Bird Topography;” a short list of “Abbreviations and Some Terms Explained;” a section on habitat and climate titled “Biogeography;” and the must-read comments on “Taxonomy” (titled “Taxonomy and Names” in the Belize volume though it’s basically the same essay but without the citation of the Birding article). The “Biogeography” sections are largely pictorial, featuring large photographs. In the Belize volume, they were taken by H. Lee Jones, author of the previous bird guide to Belize. The few pages of text pack in a lot of information on geographical location, formations, waterways, climate, types of forest and wetland habitats and the birds likely to be found in them, but the text doesn’t relate to the photos and the information is a bit squashed together. Country maps are separated out –political maps are in the “How to Use This Book” section and geographical maps are in the “Biogeography.” I really wish they had been duplicated in the back inside covers, which are blank.

Back of the book sections include Appendices on “Rare Migrants and Vagrants;” “Taxonomic Notes;” and in the Costa Rica book, a section on “Cocos Island.” There is also a listing of “References” and an “Index of English Names.” These are interesting choices. The references are books the authors used to create the guides, a mix of field guides, ornithological articles, and checklists, not a suggested source of reading for the birder using the book. I’m not saying this is good or bad, I do appreciate the careful documentation of the taxonomic notes and other materials. I am surprised by the absence of a scientific name index, especially in a world that is advocating changing English names and by Howell’s own use of alternative names for some species. Thankfully, all names–bold listed and alternative–are listed in the index; there are page references for Smithsonian Gull and Herring Gull. I’m also very happy that the index groups birds by “last name;” all the trogons are under “Trogon,” all the warblers whose name includes “warbler” are under “Warbler” (Parulas, Redstarts, and Waterthrushes have their own entries).

Size-wise, these books are of a size that would fit well into a backpack or a large vest or coat pocket. The Costa Rica book is much thicker and heavier (more birds!), and at about 2 pounds in weight might be for some of us a car book rather than a backpack book.

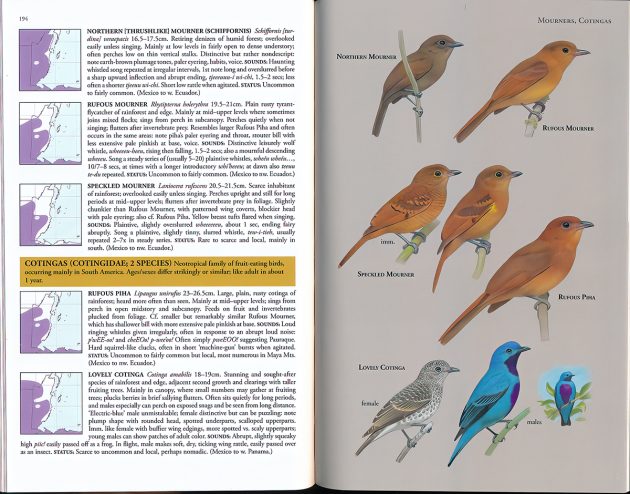

B. Birds of Belize, artwork by Dale Dyer, p. 195. © 2023 by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer

Species Accounts

Text on the left, illustrations on the right. The Species Accounts follow the ‘modern guide’ format, with illustrations clearly labeled and arranged in species groupings. The Accounts utilize the “user-friendly” field guide sequence proposed in “The Purpose of Field Guides: Taxonomy vs. Utility” by Howell and five other notable birding authors (Birding, 2009^). It starts with water and wading birds and ending with meadowlark, blackbird, and bobolink.^ Regardless of whether you think field guide sequences should or should not reflect current evolutionary sequence, it’s comforting and easy to find falcons next to hawks, vireos next to warblers.

The text is remarkably easy to read, thanks in part to a highly readable font, color-banded family and genera sections, bolded and capitalized species names and section labels, and just the right amount of space between species descriptions. Even pages that cover five different species do not seem crowded. Each family section starts with a brief encapsulation of what kind of birds are in that family, their common characteristics and the number of species in that particular country; some genera descriptions are also given. This is particularly helpful for bird families that might be new to birders. I know I would have benefitted from reading the summaries on the Typical Antbird family (Thamnophilidae) and its member groups: Antshrikes (with stout, hooked bills), Antvireos (chunky birds with fairly stout bills, like vireos), Antwrens (small, arboreal birds with slender bills), and ‘Professional’ Antbirds (“boldly patterned” antbirds that are serious followers of army ants).

Each species account starts with the English name and scientific name. A lot of attention is placed on names, reflecting the authors’ priority on past and current taxonomy. Alternate names are given in parentheses: Smithsonian (American Herring) Gull. Related names are given in brackets: Lesson’s [Blue-crowned] Motmot. Bracket names include former names for species that have been split (the Motmot) and other instances where taxonomy is “uncertain.” Size–length and sometimes wingspan–is given in centimeters. Next is the section birders are most likely to read first, a summary of the bird’s habitat, behavior, and identifying features: where and how it is likely to be seen (humid forest, fast-flowing streams, plantations, high, low, with mixed flocks, alone and quiet), significant behavior (heard more than seen, flushes, sallies for insects, soars on flattish wings, flight quick and darting), and how to distinguish it from similar birds in the area. This section also details significant plumage features for the adult bird and for the juvenile and female is needed.

Sound is next: descriptions and transcriptions of vocalizations, including cadence, repetitive sounds, and species that sound similar. The Status section is meant to be used with the distribution maps. The text indicates if the bird is a winter, summer, or nonbreeding migrant (resident is the default status) and at what elevation it is likely to be found. The maps, which are positioned to the left of the text, are small and indicate primary seasonal status–whether and where the bird is a resident breeding species, seasonal breeding migrant, seasonal nonbreeding migrant, or transient migrant. They also occasionally show breeding colonies or isolated populations, possible occurrences, and directions of range expansion.

I love the writing here. It is very specific and very detailed. There is little room for a smart turn of phrase, but the exactitude of every sentence makes each account unique and applicable to bird identification in the field. Long-billed Hermit is, “A spectacular if dull-plumaged hummer of humid forest understory…” (CR, p. 212). Bat Falcon is a “Handsome small falcon of humid forest and edge, adjacent clearings, semi-open areas with scattered trees and forest patches; locally in towns, often at Maya ruin sites” (Belize, p. 116). I was happy to see that the description in the Costa Rica guide is similar but drops the reference to Maya ruins, a detail that tells me each guide was carefully curated for its country. Keel-billed Toucan gives a “Loud throaty croak…at a distance sounds like frogs…up close has an ear-splitting, shrieking quality” (CR, p. 200). Perhaps the best examples of Howell’s expertise at writing species descriptions are the pages on those brown rainforest look-alike birds, the Woodcreepers. He distinguishes each by attention to foraging behavior, fine differences in bill size and color, and vocalization. Southern Spotted Woodcreeper has a “fairly stout straight bill extensively dark above” (p. 248), Northern Barred Woodcreeper has a “stout blackish bill with pinkish base” (p. 246), while Ivory-billed Woodcreeper’ bill is “not strikingly ivory-colored, often dusky pale pinkish overall, sometimes with a dark maxilla” (p. 248).

[There is one error in the Belize guide which is pointed out by a user on the Amazon page: the images of White-whiskered Puffbird are reversed, with the female labelled male and male labelled female. This is corrected in the Costa Rica guide.]

Author Steve N. G. Howell has a long list of bird and birding books to his credit, several of which have been reviewed here. In addition to the already mentioned A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America, co-authored with Sophie Webb (1995) and Oceanic Birds of the World: a Photo Guide, co-authored with Kirk Zufelt (2019), his titles include Petrels, Albatrosses, and Storm-Petrels of North America: A Photographic Guide (2012), A Reference Guide to Gulls of the Americas (with Jon Dunn, 2007, Molt in North American Birds (2010), Rare Birds of North America (with Ian Lewington and Will Russell, 2014), Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: West Coast (with Brian L. Sullivan, 2015), Offshore Sea Life ID Guide: East Coast (with Brian L. Sullivan, 2016), Birds of Chile: a Photo Guide (with Fabrice Schmitt, 2018), and Peterson Guide To Bird Identification in 12 Steps (with Brian Sullivan, 2018). He has also published many scientific articles on these topics in ornithological journals and articles and blog posts on taxonomy, writing field guides, and birding for popular birding magazines and websites. Howell has also been a bird tour leader with WINGS for many years, where he specializes in tours of Mexico, Central American countries, and repositioning cruises.

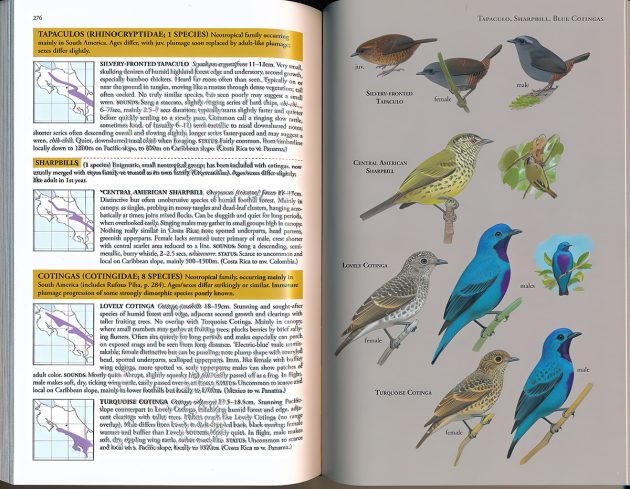

C. Birds of Costa Rica, artwork by Dale Dyer, p. 277. © 2023 by Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer

Illustrations

The illustrations by Dale Dyer perfectly complement Howell’s descriptions. A birder as well as a scientific illustrator specializing in birds, Dyer is a field associate at the American Museum of Natural History and has contributed paintings and drawings to a number of field guides, including books on Puerto Rico, the West Indies, Brazil, Trinidad and Tobago, Peru, North America, and New York State. Dyer spent many years working on these illustrations; the Preface notes that he visited Costa Rica and other Central American countries annually between 2007 and 2016. He also utilized museum specimens and speaks eloquently in interviews and on his web site about the importance on starting each bird drawing with a study of skins to understand the structure and anatomy underneath the feathers.^^

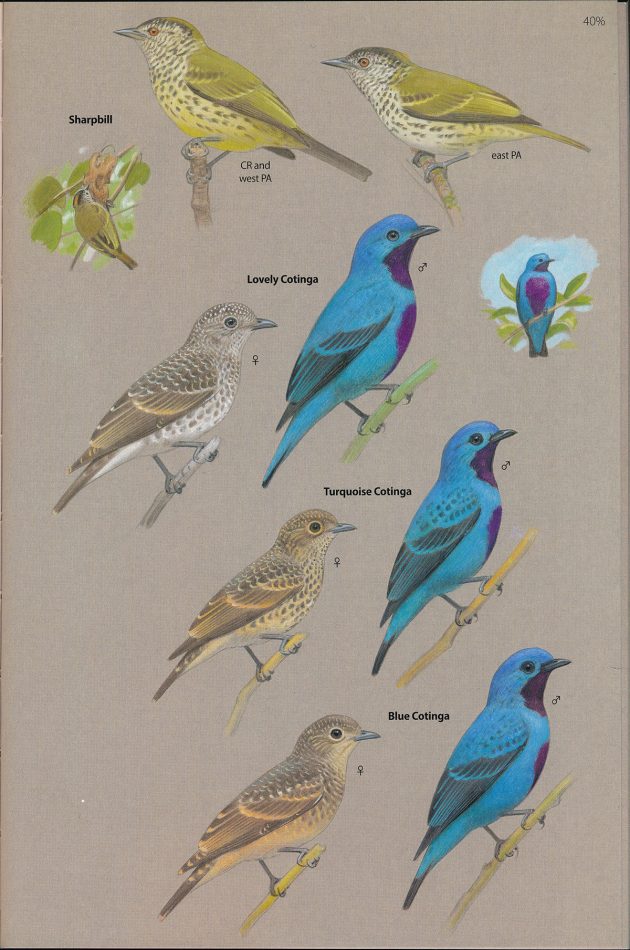

A lot of thought clearly went into the design as well as the artwork itself. Each plate illustrates two to five species, corresponding to the text on the opposite page. One to four images of each species are depicted, depending on the species; male and female Contingas are pictured in the examples above, White-rumped Sandpiper is shown in breeding, non-breeding, and juvenile plumages plus an image of it in flight. All raptor and nightjar species are shown in flight, often in multiple images, except for the tropical forest accipiters and forest falcons (perhaps because they are rarely seen?). All plumage variations are clearly labelled. Occasionally, we get behavioral vignettes like the Central American Sharpbill above, probing a leaf cluster. Species are carefully grouped on each plate so it’s easy to see which images are the same species, and when two genera or families share the same plate, Dyer very nicely has them posing in opposite directions so we know they are different.

The images themselves, apart from their utility as identification aids, are simply beautiful. They have been painted, I assume, with the watercolor/gouache method used in Dyer’s other works. Feathers glow with the subtlety of pattern and shade of colors that distinguish bird life. Bills point, claws grip, eyes glower. Each individual painting really does seem to be an individual bird. In my review of Birds of Central America, I wrote that I thought the colors were washed out on some birds. I don’t think so with these volumes, and I’m not sure if my eyes have gotten accustomed to Dyers’ work or if there have been some changes in the inking. The birds have been drawn and painted on backgrounds of varying shades of gray/blue, light blue, peach, ecru, tan/brown, etc. This works nicely to enhance the inking and relieve the eye of constantly looking at a white background, and on one delightful plate creates the lively image of standing egrets against a pale greige background counterpointed with flying egrets and a juvenile Little Blue Heron flying against a sky-blue background. The background does seem a little too dark on some plates, however, and though one can say this represents how the birds are seen in the dark rainforest, it does make it difficult to study the species in less than bright light.

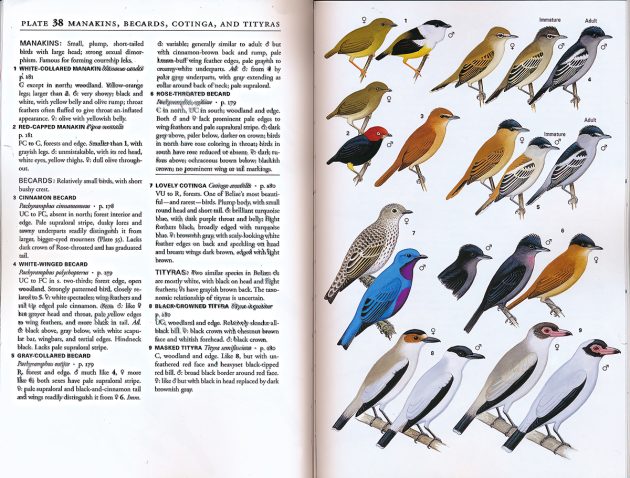

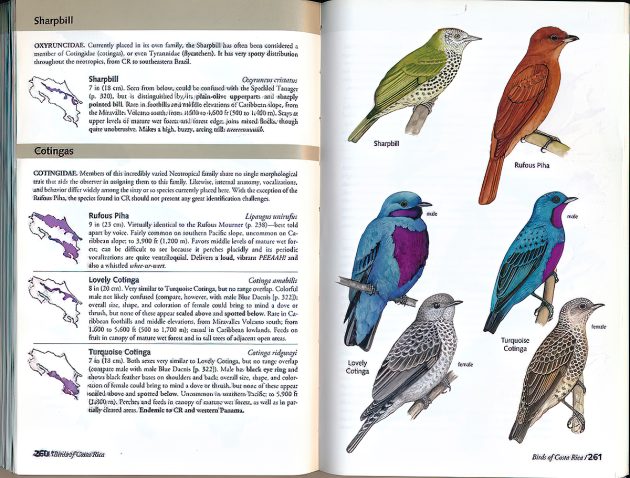

I thought it would be interesting to compare how one species is painted and configured on the page in the three books illustrated by Dyer and by two other field guides: The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide, 2nd ed., written by Richard Garrigues and illustrated by Robert Dean (Comstock, 2014) and Birds of Belize, written by H. Lee Jones and illustrated by Dana Gardner (Univ. of Texas Press, 2004). These represent, I think, the field guides used the most often before publication of these volumes. I decided to look at depictions of Lovely Continga, a sought-after species in Belize and Costa Rica. Lovely Cotinga males are a spectacular blue and purple and the females are a spectacular brown and beige, so this is a good way to see how the artists portray both ends of the bird “beauty” scale. The plates for the 2023 guides are above, the others below.

A. Birds of Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, artwork by Dale Dyer, p. 381. © 2018, Princeton University Press

D. Birds of Belize, artwork by Dana Gardner, Plate 38. © 2003 text H. Lee Jones, © 2003 illustrations Dana Gardner

E. The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide, 2nd ed, pp. 260-261. © 2007, 2014 text Richard Garrigues, © 2007, 2014 illustrations Marc Roegiers and John K. McCuen

Dyer’s artwork for the Birds of Central America guide is perfectly reproduced in the Belize and Costa Rica volumes, down to the little portrait of the male perched on a leafy branch. The main difference is that “male” and “female” are spelled out. The illustration by Dana Gardner for the 2003 Belize guide is more color blocked, less subtle, a totally different style. The Lovely Cotingas illustrated by Robert Dean for the 2014 Costa Rica guide are chunkier with rounder heads, also more color blocked. All good illustrations for field guides, but if I were to put any of these images on my wall so I could appreciate the beauty of the bird, it would be Dyer’s.

Conclusion

Birds of Belize and Birds of Costa Rica are both impressive, informative, well-organized field guides, distinguished by the expertise, experience, and talents of their authors. Birders may have thoughts about its use of alternative taxonomy, but I think most travelers will be happy to have current guides to these popular countries. There is a real need for a new guide for Belize. H. Lee Jones’ Birds of Belize is a good field guide but organized with plates separate from species accounts, and a lot has happened in the birding world since 2004. The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America by Jesse Fagan and Oliver Komar (2016) does cover Belize, but also Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

Costa Rica, on the other hand, has a rich ornithological book history, including the classic A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica by F. Gary Stiles and Alexander F. Skutch (1989), an encyclopedic treatment still worth studying. The recommended field guide has long been The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide, 2nd ed. by Richard Garrigues. I had a chance to use it in 2021 on a brief trip to Costa Rica and found out that even in less than ten years, taxonomic changes–many official splits and name changes, including the Motmot group–made a number of its entries outdated. Still, the guide was still very useable. It may be that we were not totally bereft of a decent bird guide to Costa Rica before this field guide came out, and it is true that we still lack guides to other Central American countries, like El Salvador and Guatamala. But it’s lovely to have this beautiful guide–both beautiful guides–available for study, identification, and adoration of these incredible birds.

* The Mexico guide as part of a larger project including the Costa Rica guide is cited in Howell, Steve N. G & Dale Dyer, “Costa Rica: Even Richer Than we Thought?,” North American Birds, vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 22-29. Available to ABA members at https://www.aba.org/north-american-birds-vol-73-no-1/

** Howell, Steve N. G & Dale Dyer, “Costa Rica: Even Richer Than we Thought?,” North American Birds, vol. 73, no. 1, p. 22.

*** Howell, Steve N. G. & Sophie Webb, A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America, Oxford Univ. Press, 1995

^Howell, Steve N.G., Brian Sullivan, Michael O’Brien, Chris Wood, Ian Lewington, and Richard Crossley, “The Purpose of Field Guides: Taxonomy vs. Utility,” Birding, Nov. 2009.

^^ See Dale Dyer’s website, https://sites.google.com/site/daledyerornithill/ and his interview in Angelo, Hillary, “Bird in Hand: How Experience Makes Nature,” Theory and Society, vol. 42, no. 4 (July 2013), pp. 351-368.

Birds of Belize (Princeton Field Guides)

By Steve N. G. Howell and Dale Dyer

Princeton University Press, April 2023

Pages:304, Flexibound; Size: 5.25 x 8 in. x 1 in.; Weight: 1.25 pounds

Illus: 116 color plates + 15 color photos. 600

ISBN-10 : 0691220727; ISBN-13 : 978-0691220727

Price: $35.00/£30.00 (discounts from the usual suspects); Kindle and eBook versions also available

Birds of Costa Rica (Princeton Field Guides)

By Dale Dyer and Steve N. G. Howell

Princeton University Press, May 2023

Pages:456, Flexibound; Size: 5.25 x 8 in. x 1.25 in.; Weight: 2.03 pounds

Illus: 203 color plates. 19 color photos. 900+

ISBN-10 : 0691203350; ISBN-13 : 978-0691203355

Price:$29.95/£25.00 (discounts from the usual suspects); Kindle and eBook versions also available

Leave a Comment