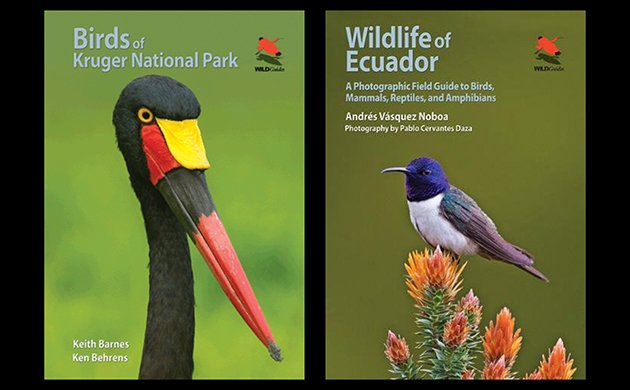

Birds of Kruger National Park by Keith Barnes and Ken Behrens and Wildlife of Ecuador by Andrés Vásquez Noboa, photography by Pablo Cervantes Daza are the latest titles in Princeton University Press’s WildGuides Wildlife Explorer Series, a series focused on the “general reader,” the layperson, the traveler who is not a “birder” but who wants to know what bird or animal or amphibian or reptile she’s observing. This is an important niche that is too often filled with laminated folders and colorful paperbacks of varying accuracy and quality. The PUP WildGuides are a quality act with high production values, knowledgeable authors, beautiful photographs, introductions in the front that describe habitat and indexes in the back. The guides are small enough to fit into a large pocket or a small backpack, and sturdy enough to withstand the wear of travel.

Birds of Kruger National Park covers the 259 species most frequently seen in the park, about half of the total number of birds documented there. Most of these are common/abundant residential and migratory birds (and, this being Kruger, that includes five Hornbill species, four Sunbird species, a Trogon, five Owl species, and many other goodies); uncommon and striking-but-rare species are also included, so we have Storks, Martial Eagle, and Pel’s Fishing-Owl.

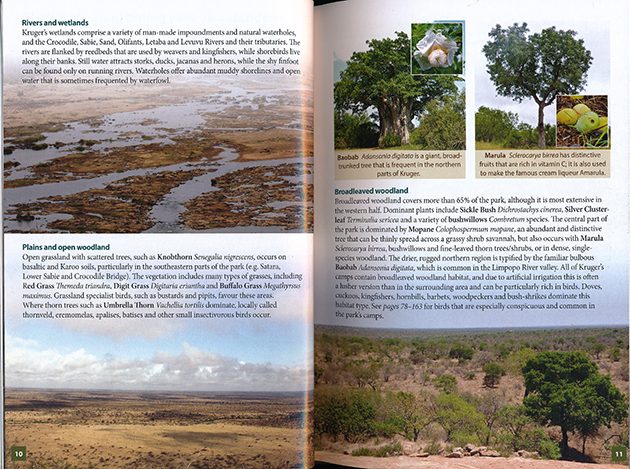

The 224-page book is organized by habitat and behavior, not taxonomy. There are the seven sections: (1) Birds of Rivers and Wetlands; (2) Birds of Plains and Open Woodlands; (3) Birds of Broadleaved Woodland and Camps; (4) Birds of Forests and Riverine Thicket; (5) Birds of Prey and Vultures; (6) Birds of the Air (swifts and swallows); (7) Night Birds. It sounds simple, but I wonder how it works in practice. Regular readers of 10,000 Birds may remember Jochen’s posts about keeping taxonomy out of field guides. Of course, this is not a formal “field guide,” but it is interesting to look at this alternative form or organization.

I have to say right off that taxonomic organization is imprinted in my brain. So, my taxonomic brain sees a couple of drawbacks immediately. One is habitat overlap– birds don’t read, so they may fly from one habitat to another and be seen there by someone using this book. A White-browed Robin-Chat, a “bird of forests and riverine thicket” may show up in your camp (in fact, this is noted in the bird’s description) or a Southern Red Bishop, a bird of broadleaved woodland, may be seen along the river. The authors tell us that birds are placed in the habitat of their “dominant behavior.” This still leaves the user flipping through sections, looking for the species in question, though I don’t think there are many species with this habitat overlap.

The second drawback is that in a few cases, birds of the same genus are separated. Kingfishers are in the Rivers section and in the Broadleaved Woodland section. Storks are in Rivers and in Plains. Cisticolas are in three sections—Rivers, Plains, and Broadleaved Woodland. There are some cross-references, but not always.

I thought about this a lot, and finally realized that most of the travelers using this book will not care. They will not find it confusing to have Kingfishers in two separate places, regardless of genus or evolution, because their goal is to identify the bird quickly. The Kruger visitor interested in nature, but not a “birder,” will be very happy to have all the birds being seen in the river in one place. A kingfisher flies by, the traveler opens the guide to the “rivers and wetlands” section, and has three species to choose from. The traveler is not distracted by the other four kingfisher species of Kruger N.P., located in the “broadleaved woodland and camps” section.

I’m really interested to hear opinions from readers. I know there are many people out there who find taxonomic organization not only confusing but also a huge obstacle to using a bird guide quickly and effectively. Does a habitat organization of species work for you?

Of course, habitat organization means that you need to know what kinds of habitats there are in Kruger N.P., and the Introduction offers descriptions of each habitat type and the three other bird groupings. The authors also discuss the best time to visit Kruger N.P., list the 21 species in the book threatened with regional extinction, and provide images showing the basics of bird anatomy. The two maps of habitat distribution and the park’s camps, rivers, and main roads may be helpful for planning, though the habitat map is much more detailed than the habitat organization of the book, making it difficult to match one to the other.

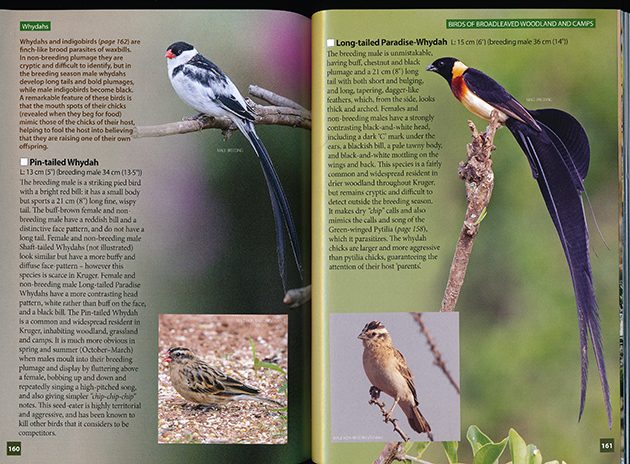

The Species Accounts tell us the birds’ stories, and a lot of information is packed into these paragraphs: appearance; age and gender differences in appearance; how the species differs from similar birds; interesting behavior or nesting notes; whether it is common or uncommon or rare; migratory or resident, breeding or nonbreeding in Kruger N.P.; where the bird is most likely to be found in the park; and whether the species is declining or increasing. Details vary for each species. Vocalizations are mainly given for passerines–mostly, it seems, when it is important to know the vocalization to locate the bird. Scientific names are not given in the species accounts; they are listed alphabetically with page number of species account in a separate index in the back. Within each habitat section, birds are grouped by genus or other unifying trait (strange waterbirds, common camp residents, canopy gleaners). Notes on some of these groups expand on interesting behavioral or even cultural facts (in some African cultures, for example, doves are considered villainous), making this guide more appealing to the layperson.

The Accounts are approximately 50% text and 50% photographs, but it is the photographs that dominate the eye. They are medium to large in size and quite striking, Many of the photographs show the bird in its habitat—perched on logs, striding through fields, drumming a hole in a tree, with the river or plains or forest background a muted blue or green or brown that extends to the whole page. Photos of the bird in flight accompany most hawk accounts (not the vultures), as well as waders, shorebirds, rollers—generally all birds that are likely to be seen in flight in Kruger. The authors note that “where possible, images of males, females, juveniles and alternative plumages are included and annotated.” I was happy to see the female/nonbreeding Pin-tailed Whydah male, with its short tail and little-brown-job bod —quite a contrast to the excessively long-tailed breeding plumage male, and one that astonished me when I first saw it.

Photographs are mainly by the authors; approximately 20% are by colleagues and nature photographers who are credited in the back. Other back of the book material includes recommended Further Reading (including the classic Southern Africa field guides), online resources, scientific name index, common name index (nicely done), and a handy Short Index of group names on the inside back cover.

Authors Keith Barnes and Ken Behrens are experienced African birders, bird writers, and trip leaders. Both men lead trips for tour company Tropical Birding (Barnes is a founder), and they have also co-authored Wildlife of Madagascar (another WildGuide volume, 2016), Birding Ethiopia (with Christian Boix, 2010) and Wild Rwanda (with Christian Boix, 2015). Barnes, a native of South Africa, also wrote the companion book to this one, Animals of Kruger National Park (2016), and The Important Bird Areas of South Africa (1998). Behrens, who comes from United States, also co-wrote the innovative Peterson Reference Guide to Seawatching: Eastern Waterbirds in Flight (with Cameron Cox, 2013).

They have here created a bird guide that is an excellent companion to Animals of Kruger National Park; together the visitor to Kruger National Park has all the information she (or he) needs to enjoy one of the great reserves in the world. Birders will want to take along one of the comprehensive field guides to birds of southern Africa, but if you have the space and the funds, this is a handy guide to have with you in the field (because those comprehensive guides are big. And, heavy.)

Wildlife of Ecuador: A Photographic Field Guide to Birds, Mammals, Reptiles, and Amphibians is the all-in-one nature guide for the generalist nature traveler. It could also serve as a backup guide for the birder traveling with a more comprehensive birding field guide (keep in mind that the classic by Ridgely and Greenfield is 740 pages long and measures over 2 inches in width), though even with accounts for 223 bird species the guide is covering only 14% of the 1620 bird species documented in Ecuador. The guide also covers amphibians (37 species), reptiles (40 species), and 71 species of mammal. The diversity and breadth of biodiversity in Ecuador is huge–over 580 amphibian species, 457 reptile species, 1620 bird species (including those of the Galapagos), and 327 mammal species, so this relatively small guide (286 pages) necessarily only represents the most common and well-known creatures one is apt to see in mainland Ecuador.

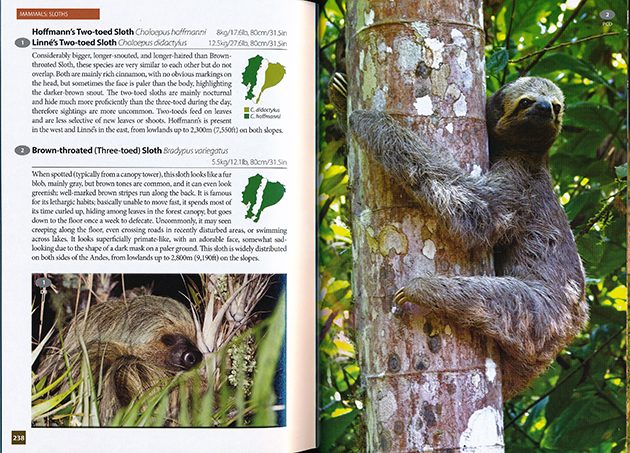

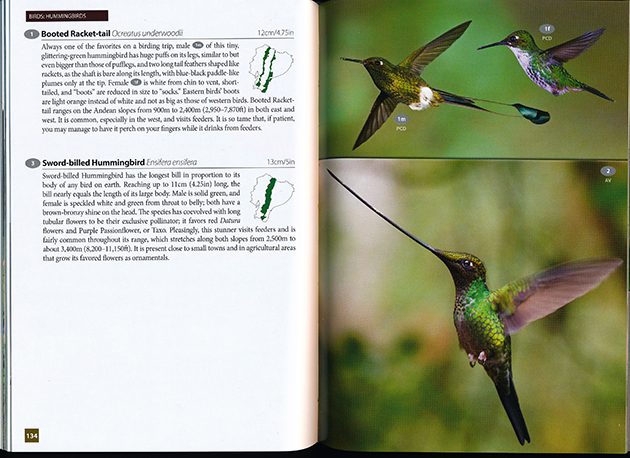

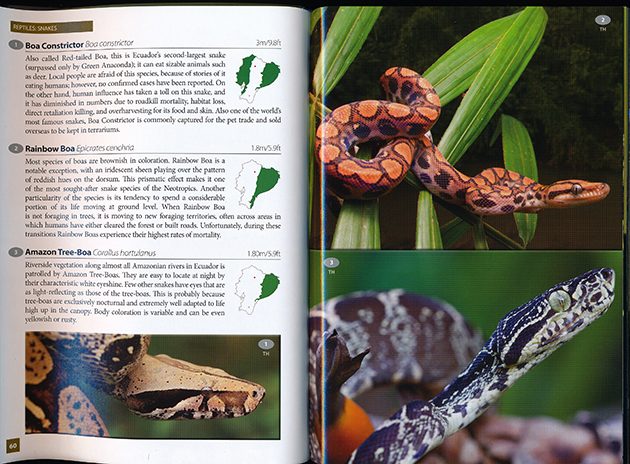

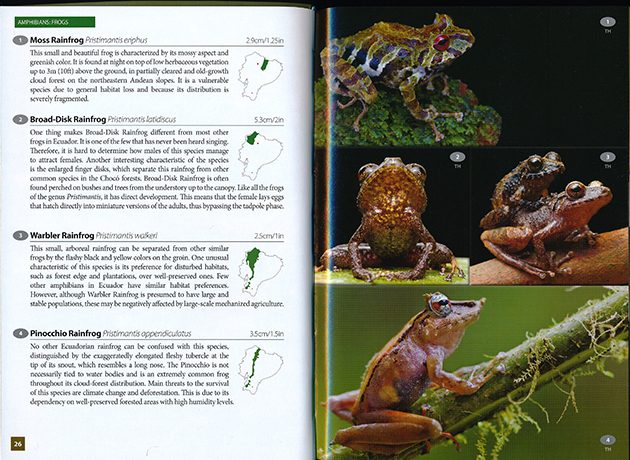

Species accounts across the board are succinct: Common name, scientific name, size in centimeters and inches, small range map showing distribution, main identification features, habitat, and, occasionally, notes on behavior, especially as they impact on locating the creature. You can find the Pygmy Marmoset’s family feeding tree by looking for its markings on the trunk, similar to those made by sapsuckers. Warbler Rainfrog is one of the few rainfrogs that prefers disturbed habitats. Sword-billed Hummingbird, one of the “star” birds of Ecuador, prefers the long-tubed red Datura flowers and Purple Passionflower. Amazon Tree-Boa can be located at night by its white eyeshine.

Photographs are large (a quarter to a full page), clear, and colorful, and often delightful. I particularly like the frog photographs, which show off the rich, deep colors of these creatures, some extremely small. It’s not easy being green. Or ochre or gold or crimson or rosy pink. The very talented Pablo Cervantes Daza, nature and photography guide for Tropical Birding Tours and Capturing Nature Tours, did most of the photography; a handful of additional contributors are credited in the back.

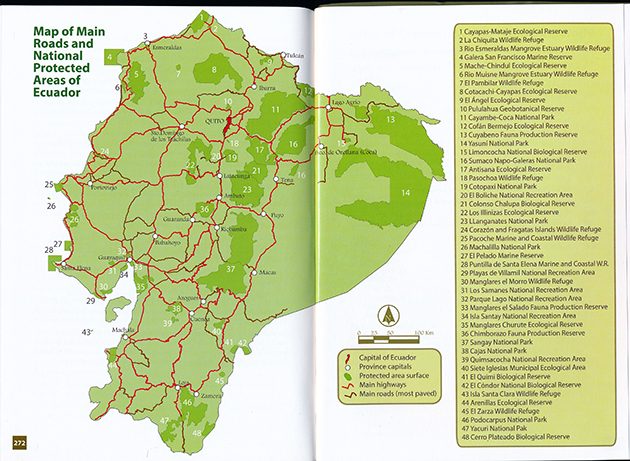

The brief introduction focuses on the “Biogeography of Ecuador” and its “Habitats and Bioregions.” This is important information, but I would also have liked a little more background on which species are covered and which are not (there appears to be an emphasis on birds seen in the popular Mindo area for example, but few of the Antbirds, Antwrens, Antshrikes, etc. that are found in the Napo River area). Back of the book material includes a two-page Bibliography, including websites like eBird and Nick Anthanas’ excellent online gallery of neotropical bird photographs; a map of Ecuador showing major reserves refuges, and parks (see illustration above); an Index of Common Names and an Index of Scientific Names (both divided by section).

Author Andrés Vásquez Noboa is a native of Ecuador and works as a guide for Tandayapa Bird Lodge and Tropical Birding Tours. Yes, all the authors of these two wildlife guidebooks are associated with Tropical Birding. I can’t help thinking that developing and writing these books is partly the result of the many questions they’ve received over the years. I imagine that at one point they were hanging out in the Tropical Birding office talking about the questions they’ve heard over and over, and finally said, “Let’s write guidebooks about the wildlife of our countries. Really good, factual guidebooks with great photographs, easy to use, emphasizing habitat that will lead to a value for conservation, highly readable with no technical language. Ready, set, go!” Mission accomplished.

I like sloths. There are no aspersions on the authors implied by ending this review with this photo. I simply like sloths.

Birds of Kruger National Park

by Keith Barnes & Ken Behrens

Princeton University Press, 2017

Paperback, 224p., 6 x 8, $27.95 (discounts from the usual sources)

Available in eBook formats including Kindle, ISBN: 9781400880683

Wildlife of Ecuador: A Photographic Field Guide to Birds, Mammals, Reptiles, and Amphibians

by Andrés Vásquez Noboa, Photography by Pablo Cervantes Daza

Princeton University Press, 2017

Paperback, 288p. 6 x 8, $29.95 (discounts from the usual sources)

ISBN: 9780691161365

Available in eBook formats, ISBN: 9781400885053 |

Leave a Comment