Or How a Serbian Suave Playboy Promoted Birding the Caribbean

Oh, the joys of slipping through the pages of a new book that has just arrived, the Birds of the West Indies by Kirwan, Levesque, Oberle and Sharpe. I am checking the References and one name, expectedly, stands out: Bond, J. Is it even possible to bird the Caribbean without the feeling that James Bond birds over your shoulder, telling you: That may be an incorrect ID, recheck that one?

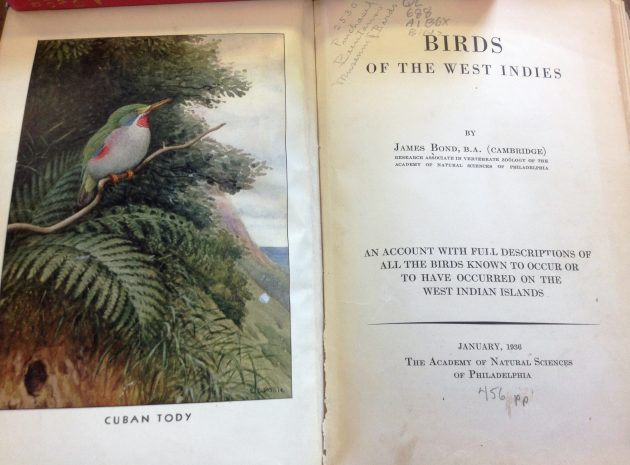

Dr James Bond published his field guide to the Birds of the West Indies in 1936, and nowadays that first edition (above) is a highly sought after collector’s item. Yet, it will be several more years until James Bond was born.

The year was 1941. Late June night at the Casino Estoril, then the largest casino in Europe, located in the neutral Portugal where spies of all colours met. The casino was thick with people and tobacco. Through the smoke, Bloch, a wealthy Jew from Liechtenstein, complained on limits and asked for unlimited bets. An affluent Serbian playboy, who spoke English, Italian, French and German, accepted the challenge and threw down an outrageous $40,000 baccarat bet (roughly $700,000 today). Humiliated, Bloch pulled away.

The charismatic playboy was Dusko Popov (right), a double agent recruited by German Abwehr, the Wehrmacht’s intelligence arm (codename: agent Ivan), but actually feeding them carefully fabricated lies while truly working for British MI6 (codename: agent Tricycle; or as the BBC has put it, the only “appropriate codename for a playboy double agent who had a penchant for ménage a trois”).

The charismatic playboy was Dusko Popov (right), a double agent recruited by German Abwehr, the Wehrmacht’s intelligence arm (codename: agent Ivan), but actually feeding them carefully fabricated lies while truly working for British MI6 (codename: agent Tricycle; or as the BBC has put it, the only “appropriate codename for a playboy double agent who had a penchant for ménage a trois”).

Shadowing Popov that night at Estoril was another British agent, himself working for the Naval Intelligence. That agent’s name was Ian Lancaster Fleming.

In order to establish a new Abwehr network, in August 1941 Popov was displaced to New York, where he rented a Fifth Avenue penthouse, bought a car to match and partied with the rich and famous of the time, including dating a Hollywood star Simone Simon (*, **). There’s a lot more Bond style trivia on Popov himself, as he was a principal agent in some of the most significant events in WWII – Pearl Harbor and D-Day.

Living in the Caribbean, in 1952 Fleming was writing the Casino Royale. In it, Bloch becomes LeChiffre, Fleming becomes Mathis and Popov becomes 007 (it does sound a bit better than Tricycle Licensed to Kill), while the rest of the gambling scene remains the same. A birder himself and looking for a name for his literary child that would sound “as ordinary as possible”, Fleming’s eyes were hovering over his bookshelf until he spotted the Birds of West Indies by James Bond. And that is how the Bond was born.

As an homage, a contemporary edition of the Bond’s field guide Birds of the West Indies was featured in the twentieth 007 film, Die Another Day (2002), where Bond (Pierce Brosnan) in Cuba poses as an ornithologist. The name of the author was carefully scratched off the front cover of the book.

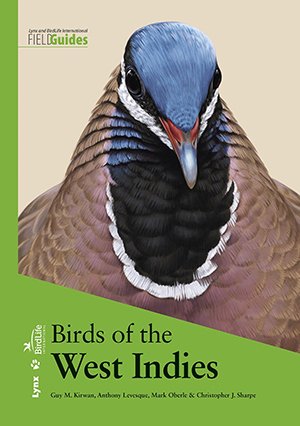

Now that I have got your attention, let us move to the new version of the Birds of the West Indies by Kirwan, Levesque, Oberle and Sharpe, published by the Lynx Edicions (2019). One other Bond’s legacy lives within it, the very concept of the West Indies zoogeographical sub-region as we know it today. In the 1970s Bond proposed borders of the region, excluding the islands along the South American continental shelf (e.g. Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire) and that border is known as the Bond’s line.

Now that I have got your attention, let us move to the new version of the Birds of the West Indies by Kirwan, Levesque, Oberle and Sharpe, published by the Lynx Edicions (2019). One other Bond’s legacy lives within it, the very concept of the West Indies zoogeographical sub-region as we know it today. In the 1970s Bond proposed borders of the region, excluding the islands along the South American continental shelf (e.g. Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire) and that border is known as the Bond’s line.

I just love the fold-able plastic covers of this book. Having a tropical maritime climate, birding the West Indies comes with a lot of water, from sea spray to humid forests. My wife’s first impression was: “This is waterproof.”

Within its 400 pages, the Birds of the West Indies covers 712 species, 550 of them regularly occurring and 190 of those endemic to the region, many of them to single islands. Furthermore, there are six families confined to the Greater Antilles. The systematics and taxonomy used in this field guide follow the two volumes of the HBW and BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (del Hoyo & Collar 2014, 2016) with some updates based on subsequent research that have already been adopted by BirdLife International and HBW Alive.

The first author, Guy Kirwan, is a freelance editor and ornithologist, and a regular visitor to the West Indies since the early 1990s, who is currently finalizing a detailed checklist of the birds of Cuba. Mark Oberle is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Washington and has worked in biology and ornithology in the American tropics for four decades. Anthony Levesque arrived in Guadeloupe in 1998. An active birdwatcher, he has found more than 50 species new to Guadeloupe, the Lesser Antilles and, in some cases, the Caribbean as a whole. Chris Sharpe is a biologist who has worked on the conservation of Neotropical birds for more than 30 years, having been based for most of that time in Venezuela.

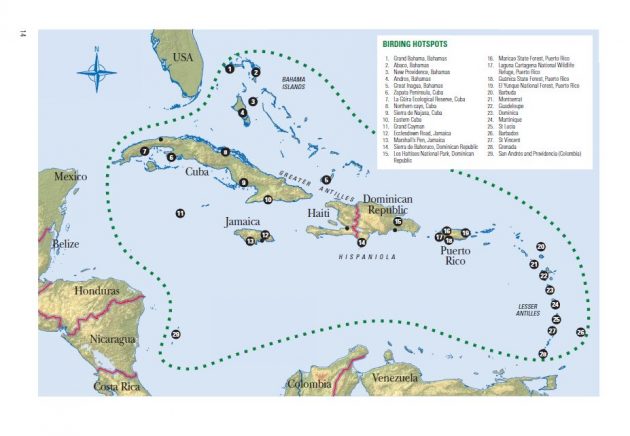

The Introduction covers some usual and expected topics, such as geographical scope, climate, habitats, bird conservation in the region (including the list of threatened species and their main threats), etc., but also some less expected such as birding the West Indies (covering topics ranging from traveler’s health – do not remember ever seeing that in a field guide – to the birding hotspots with an one-page map plus 5 pages of descriptions).

The Bond’s line

The Bond’s line

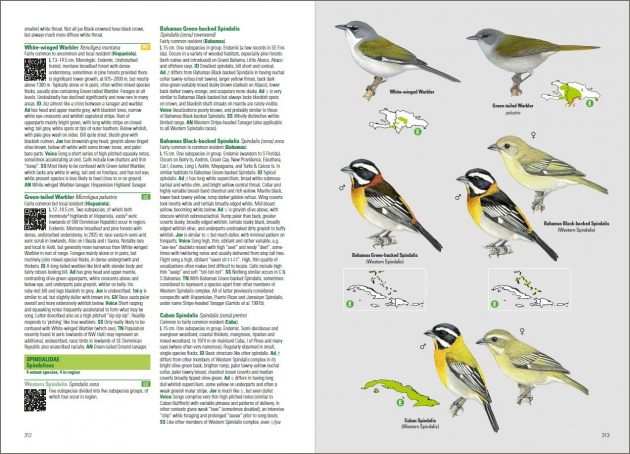

The field guide proper follows the standard format of plates on the right (in this case, with 650+ range maps within the plates) and the textual description of status, habitat and behaviour, age, sex and geographical variation, voice, and confusion species, together with QR codes (linking each species to the Internet Bird Collection gallery of photos, videos and sounds) on the left hand side.

Each species description starts with one novelty, compared to most other field guides, providing separate accounts and illustrations for each subspecies group recognized under current HBW/BirdLife taxonomy. Each account commences with a list of recognized subspecies that occur in the region and their general ranges in the country. If a species is monotypic, this is clearly stated.

The descriptions end with taxonomic notes focused on recent, species-level changes in HBW/BirdLife taxonomy. Notable deviations, especially in relation to the list maintained by the American Ornithological Society (formerly American Ornithologists’ Union), are explained.

The paintings are the work of 29 artists, but they go together smoothly, with only barely noticeable difference in styles. The illustrations are precise, detailed and beautiful, reaching about the right number of species per page, so they are not overcrowded, nor bare in places. The colours are realistic, and, on this scale, the details are visible. Pity, the already traditional Peterson style arrows are missing.

At page 335 the regional checklist begins, covering species’ statuses in each country/territory of the region: Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, Cuba, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Anguilla, Saint Martin, Saint Barthélemy, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Antigua and Barbuda, Montserrat, Guadeloupe, Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada, Barbados, Isla de Aves, Swan Islands, San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina.

The appendix II (pg. 375) covers species that are vagrants in the region coming from the introduced populations elsewhere and the potential vagrants; followed by references, and English and scientific indexes.

With each copy of the book, you get the West Indies checklist card, with a Lynx Edicions website page link and your personal code to download the .pdf that follows the same taxonomy as your field guide (and you would not want it any other way). Besides the usual checkboxes to tick your sightings, it offers the additional info which hotspots to search for the target species. The hotspots are numbered and up to 16 numbers follows the species name, with the best hotspots for the species in question marked in orange, to stand out in the crowd.

Usually, I like to weigh both pros and cons for each field guide I review, but this book poses a problem for me: I couldn’t find any cons! Oddly, a worthy conclusion on this publications comes from its authors, in the Introduction. As they say, this is a “guide that builds on the best traditions of those that preceded us; consequently, we have aimed for a book that is at once attractive, portable and discusses many of the key identification issues, but is also scientifically accurate, in the best traditions of James Bond.”

Hence, be aware: birding the West Indies, you are following the footsteps of none other but 007.

=========================================

* As a matter of curiosity, a year later (1942) in the first version of the Cat People, Simon will be playing the leading role of Irena Dubrovna, a Serbian fashion illustrator in New York City who believes herself to be descended from people who shape-shift into panthers when sexually aroused or angered. According to legend, the Christian residents of her home village turned to witchcraft and devil worship after being enslaved by the Mameluks (source). During the filming, Simon was under the FBI surveillance because of her affair with Popov.

** In the same period (WWII), there actually was a Serbian fashion illustrator in New York, Milena Pavlovic Barilli. She is the only Serbian artist whose illustration is featured on The US Vogue’s cover page, and one of the female artists whose work was selected by Peggy Guggenheim for her Exhibit by 31 Women, alongside famous names like Frida Kahlo (source). Now, was Barilli the role model for Irena Dubrovna?

I am actually in the West Indies right now, and saw a real Western Spindalis just 15 minutes before seeing the image of one in your post!

🙂

Wish I were there too 😉

No, you probably don’t. Right now it’s something like 42C, high humidity, no breeze… Maybe do your trip in December. 😉

Oh yes I wish I were there.

It was 38oC and humid here at the Danube riverbank for days/weeks and will be again from tomorrow onward, yet here there are no parrots nor swaying coconut palms around…

And I have a dominant migratory gene, always having an urge to be somewhere where I’m not.

So, yep. I would.

what a delightful article!!!!

Thank you, Peter 🙂

Great article, and oddly enough I found it while writing an article about birding with Anthony Lavesque on Guadeloupe in December. I had just described him as having steely Daniel Craig good looks. Craig, as you may recall, most recently played 007.

Oh, well, that is probably as close as one can get to birding with 007 these days 😉