Birders of the 21st century have it good, especially those of us who speak and read English. We can bird all over the world, and although we are not guaranteed a field guide to every single region and country in the world, there are a whole lot more of them than in the mid-1970’s, when world birders like Phoebe Snetsinger often had to put together their own checklists and guides. Dragonfly and damselfly enthusiasts are not as fortunate, butterfly lovers just a little more so. I found this out last year, on a trip to France with my daughter Sarah. It was NOT a “birding trip”, but that didn’t stop me from looking at and photographing every bird, dragonfly, and butterfly I could get into my viewfinder. There was one special birding day in the Fontainebleau area with French birder Jean-Marc, where I also saw exceptionally beautiful damselflies, similar to our jewelwings. I couldn’t wait to give names to all my new species.

Identifying the birds was easy thanks to the Collins Bird Guide. Once home, I realized I also needed field guides for odonates (dragonflies and damselflies) and butterflies (no moths this time!). Mostly odonates, since I had only photographed three butterflies. I tried using the Internet, but found it frustrating for all the usual reasons; websites either didn’t include all species or were difficult to use for identification. Plus there is my librarian-ish reluctance to use anything on the web for reference unless I know the author or the author’s credentials. My dreams became haunted with odonate images as I spent evenings searching for demoiselles and libellules online.

I did notice that many French dragonflies depicted on the Internet (at least those from northern and central France) are also found in Great Britain. Which is the story of how I ended up using Britain’s Dragonflies: A field guide to the damselflies and dragonflies of Britain and Ireland, 2nd edition, by David Smallshire & Andy Swash to successfully identify my French dragonflies and damselflies. The book is produced by WILDGuides, a nonprofit publishing organization that joined forces with Princeton University Press last year to create the Princeton WILDGuides imprint. Besides the urgent need to identify my dragonflies, I was interested in hands-on experience using these field guides. I liked Britain’s Dragonflies so much, I decided to review it here, and I thought I would double my pleasure and yours by also reviewing Britain’s Butterflies: A field guide to the butterflies of Britain and Ireland, 2nd edition, by David Newland, Robert Sill with David Tomlinson and Andy Swash.

These photographic field guides are lovely to look at and easy to use, providing a variety of tools for species identification. Though a little larger, at 6-inches x 8-1/2-inches, then pocket-sized, they fit handily into a backpack. Sturdy plastic over the paperback covers and a ruler on the inside back cover clearly say that these books are designed to be used outdoors. The compactness of both books (Dragonflies is 208-pages and Butterflies is 224-pages long) of course stems from the small number of each type of insect in Great Britain and Ireland; comparative field guides for Europe and Great Britain are necessarily longer and heavier.

Each book is organized into three parts: (1) Introductory material, including sections on biology, where to look for species (habitats), identification principles, and a glossary; (2) Species Accounts; (3) Information on early life stages (larvae and exuviae for dragonflies, eggs, caterpillars and chrysalises for butterflies), how to watch and photograph dragonflies and butterflies, and reference material, such as additional reading suggestions, and an “Index of English and scientific names”. The books (and, I assume the series) share a web-type design construct in which information is organized visually, by blocked colored spaces, bar separators, and size and color of font. It’s a great idea, and one that is becoming increasingly popular in the field guide world; the graphic approach helps naturalists, especially beginners, cognitively organize new information that might be overwhelming. Rob Still, WILDGuides publishing director and chief designer (and also co-author of Britain’s Butterflies) is responsible for the books’ design.

Both books were developed with the support and input of nonprofit associations, the British Dragonfly Society and the Butterfly Conservation; portions of the proceeds from book sales support these organizations.

Britain’s Dragonflies: A field guide to the damselflies and dragonflies of Britain and Ireland

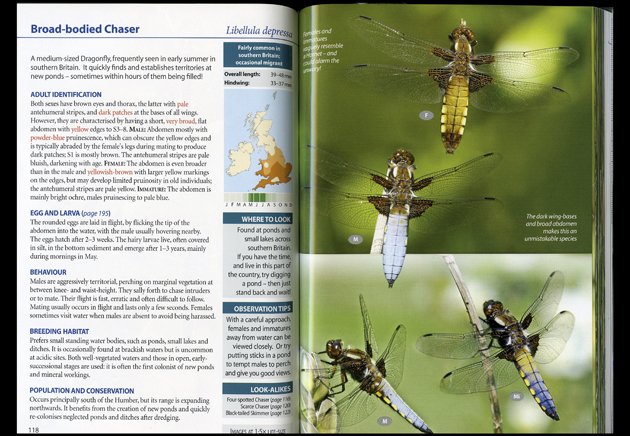

I’m going to look at Britain’s Dragonflies first. It covers 63 odonate species: 44 breeding species (19 damselfly, 25 dragonfly), and, in a second part of the Species Accounts, 19 vagrant, potential vagrant and former breeding species (5 damselfly, 14 dragonfly). Each species account is 2-pages long, one page of text and one page of photographs. Here is the species account for Broad-bodied Chaser, Libellula depressa. It easily helped me identify my photograph of what I call the “fat dragonfly” as an adult female Broad-bodied Chaser. The jewelwing is Calopteryx virgo, appropriately also called Beautiful Demoiselle.

Each account starts off with English popular name, scientific name, and, for some species, Irish and European popular name. The section on physical description, called Adult Identification, details common, male, female, and immature characteristics, with diagnostic features lettered in red. The where and how of egg laying and larva emergence is briefly treated, with page references to larval drawings at the back of the book. Sections on Behaviour, Breeding Habitat, and Population and Conservation offer brief but specific information. The Behaviour paragraph includes flight pattern and mating habits. Species Accounts for vagrant species are slightly different, with no Egg and Larva information, and a Status section replacing Population and Conservation, listing documented records of where and when the species was sighted or where it used to breed in Great Britain and Ireland. A right-hand sidebar encapsulates basic facts–common or scarce, widespread or endangered, overall length and hindwing length, where to look, observation tips, look-alikes (just a list). It also contains a small but legible distribution map showing breeding range and flight months.

The one thing I missed here was more information on distinguishing look-alike species. This is occasionally included in the Adult Identification section, thankfully for the red damselflies. And, to be fair, with the small number of species located in Great Britain and Ireland, there is far less confusion than in North America. Again, I really like the use of design and fonts to draw the eye to diagnostic features immediately.

The photographic page for each species presents the damselfly or dragonfly in a number of images, usually full frontal, sometimes in profile, sometimes, helpfully, in a typical perched or mating position. The images are merged into one photographic plate. This is a change from most photographic field guides, which present each image separately. Most of the species accounts offer four to eight images; this is especially useful for damselflies, who are likely to appear in variable color forms. The authors have drawn on the work of 45 photographers, including the authors; hundreds of new photographs have been added to this second addition. The plates are labeled for gender, age (only immature, the default is adult), and feature bits of identification tips. Female and immature Broad-bodied Chasers, we are told for example, “vaguely resemble a Hornet – and could alarm the unwary!” A note on the bottom of the adjoining sidebar tells us whether the images are life-sized, 1.5 life-sized, or twice as big as life.

The quality of these photographs is excellent; they are also beautiful. Color reproduction appears to be accurate, and the labels are placed unobtrusively, so they don’t detract from the details and drama of these predatory insects. In many cases, species images are placed in parallel positions, making it easy to compare morphs and genders. I suspect that some users will find the photographs that show the dragonflies in their natural habitat a little too busy. I like them, they mirror what we see in the field, and the dragonfly images are sharp enough that they don’t get lost in the green leafy backgrounds. I also like the way the images are arranged so that the tip of an abdomen overhangs from one section of the plate to another. It shows a nice attention to detail.

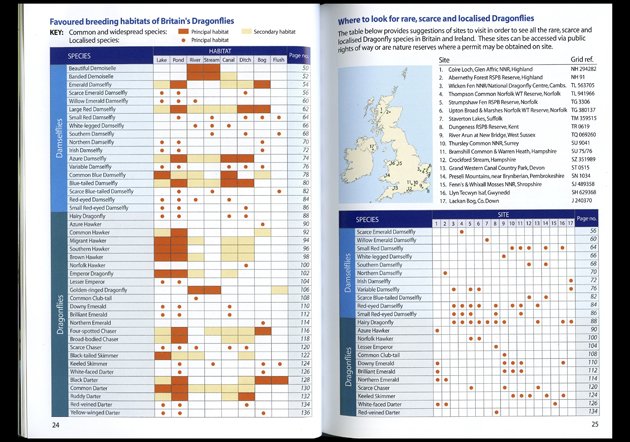

Time to go back to the beginning of the book. The introductory chapters are good examples of educational text made fun and readable. Life cycles of odonata are described with a minimum of scientific language, accompanied by photographs illustrating stages–egg laying, larva, emergence, aging, mating, dispersal. In fact, visuals dominate all the introductory sections. The chart above shows Favoured breeding habitats of Britain’s Dragonflies; it follows 3-pages which illustrate each habitat type. The section on How to identify Dragonflies offers photographic diagrams of anatomical parts, a required feature of all dragonfly field guides, and something new, a wonderful series of charts on species identification. Abdomen patterns, thorax sides, wings, legs, eyes, private parts, and more are compared visually and textually. I do wish that the one-page Glossary was more comprehensive and included the more basic scientific terms like “thorax” and “abdomen”.

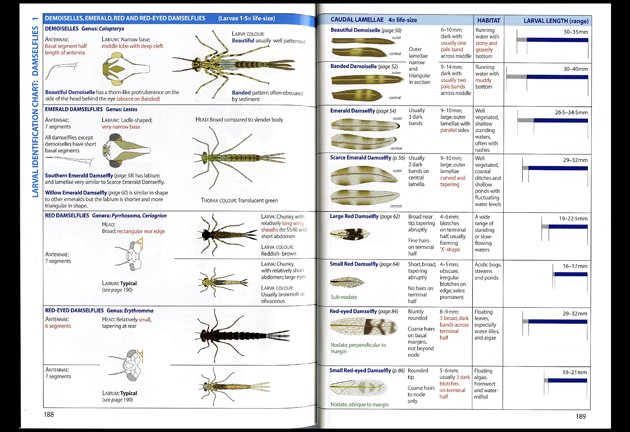

Most of the back-of-the-book material is on identification of Larvae and exuviae, offering detailed identification charts, like the one above on Demoiselles, Emerald, Red and Red-eyed Damselflies, anatomical diagrams, and photos. This is a very unusual feature for a dragonfly field guide; most guides focus almost exclusively on damselflies and dragonflies in their adult form. (There are probably at least a few people like me who look at those larvae photos and go, “Ewwwww,” but the more likely explanation is that the adult forms are much prettier and a whole lot easier to observe.) The authors explain the importance of documenting this stage of the life cycle. Larvae and exuvia mean breeding, and breeding data contributes to knowledgeable conservation plans. The section thus ties in nicely with WILDGuides identity as a conservation-minded publisher.

The authors pay far less attention to photographing and collecting adult dragonfly specimens. The emphasis is on photography, with collecting said to be “the domain of a few serious taxonomists”. I’ve been looking at Dragonfly News, the magazine of the British Dragonfly Society, and it looks like this is the culture of dragonfly enthusiasts in Britain; none of the group photos showed people holding nets, like they do here at DSA (Dragonfly Society of the Americas) meetings. If there are any dragonfly people from Great Britain out there who can confirm this, please let us know.

The authors of this field guide are both nationally-known odonate experts. Dave Smallshire is a former agricultural entomologist and environmental consultant who now leads nature tours around the world for Naturetrek, and speaks and writes about dragonfly surveying and conservation. He is a trustee of the British Dragonfly Society and convenes its Dragonfly Conservation Group. Andy Swash is a zoologist and professional ecologist who co-founded WILDGuides in 1999. In addition to co-authoring and editing many of the company’s field guides, he is a nature photographer with a portfolio of thousands of bird, dragonfly and butterfly images.

Britain’s Butterflies: A field guide to the butterflies of Britain and Ireland

When I first looked through this book, I thought it was déjà vu and that I was looking at many of the same species we have here in the northeast United States. A rookie mistake, I eventually discovered. Yes, we do share some species; we both enjoy Vanessa cardui, Painted Lady, Vanessa atalanta, Red Admiral, and several skippers (I’m sure there are others, these were the ones I identified while comparing checklists). There are many more British species that resemble ours, but belong to different subfamilies or even families. Fritillaries, always a tricky id, are a good example. I look at the photos of High Brown Fritillary and think it is a mirror image of our Variegated Fritillary. And, then I look at the scientific name and see that the species are not even related. High Brown Frit belongs to the Argynnis family and Variegated Frit is part of the Speyeria family.

My recommendation is to ALWAYS use the scientific name if you are a North American naturalist. Not only are physical appearances misleading, the North American and British checklists share several popular names for completely different species. Silver-spotted Skipper in Britain is not Epargyreus clarus, a small orange-brownish skipper with a bright silver-white band on its hindwings. It is Herperia comma, the skipper we call Common Branded Skipper, a smaller orange-brownish skipper with several white spots on its hindwings. I think British and American lepidopterists need to talk more.

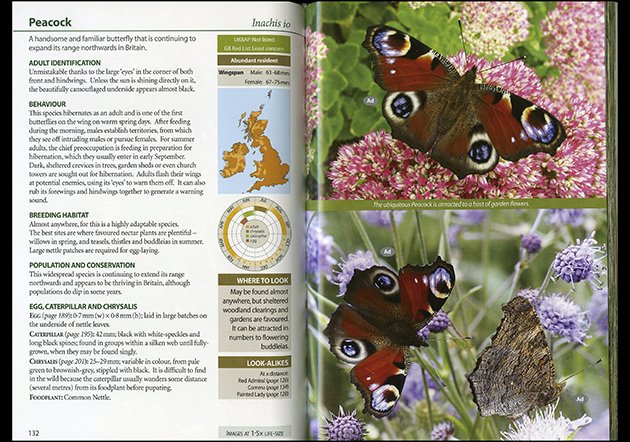

Like Britain’s Dragonflies, the Species Accounts in Britain’s Butterflies follow a strict formula: two pages for each species, one of text, one of photographs; the text page organized into sections with a sidebar, the photographic page showing merged images of the butterfly from varying viewpoints. The Species Account for the Peacock, Inachis io, is shown above. The guide covers the 59 butterfly species that currently breed in Britain and Ireland, and, in a separate section, four former breeding species and 10 vagrants. The order is slightly different from a strict taxonomic listing; besides separating out non-breeding species, the Breeding and Annual Migrant Species are organized with similar-looking species placed close together for ease of reference.

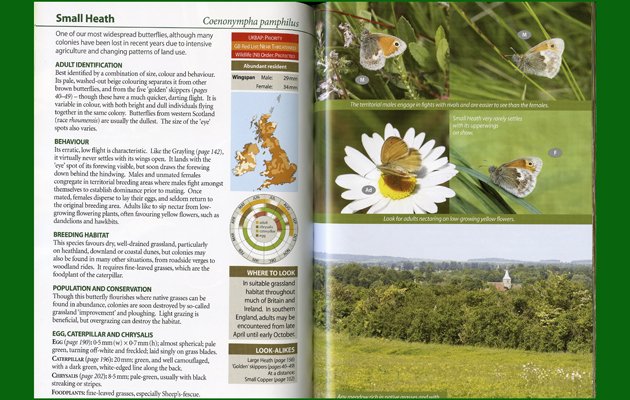

The text page consists of sections on Adult Identification; Behaviour; Breeding Habitat; Population and Conservation; and Egg, Caterpillar, and Chrysalis. I was a little disappointed in the Adult Identification text, which focuses more on distinguishing the subject butterfly from similar species, than on giving a description of actual color and patterning. So, Small Heath, Coenonympha pamphilus, is described as having “pale washed-out beige colouring” and being “variable in colour, with both bright and dull individuals flying together in the same colony” and having ‘eye’ spots that vary in size. I understand that we are supposed to be looking at the excellent photographs as we read this, and that the authors do not want to use more technical language required for more detailed descriptions (for example, basal spots, postmedian band). But, the lack of specificity makes this field guide more suitable for beginners than experienced butterfly enthusiasts.

Sidebar sections consist of lists the species’ endangerment and protection status, if any; its reidential status in Britain and Ireland; measurements; habitats where the butterfly is likely to be found, look-alike species, and the scale of the photographs on the next page. A small distribution map shows main and secondary breeding areas in Britain and Ireland, and a life cycle chart shows months of the various stages.

The attention given to butterfly status and conservation in this guide reflects both its association with the Butterfly Conservation and the fact that butterflies are decreasing in numbers. Butterfly Conservation reported a 20% drop between 2010 and 2011 recently, and we find out here that 19 out of 59 breeding species are marked critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable with another 11 considered near threatened. This is the not-so-secret mission underlying this book’s publication: to get people more engaged with butterflies, more conscious of their status, and more invested in actions and funding to save them.

Photographs in the Species Accounts and elsewhere are credited to 26 photographers, including three of the authors (Newland, Still, and Swash). They all show the butterflies in their natural habitats, and many of the Species Accounts include a photo of the habitat itself. Small Heath, for example, is found in meadows rich with native grasses. Both sexes are shown from above and from the side; sexes are labeled and there are additional notes with identification and location tips.

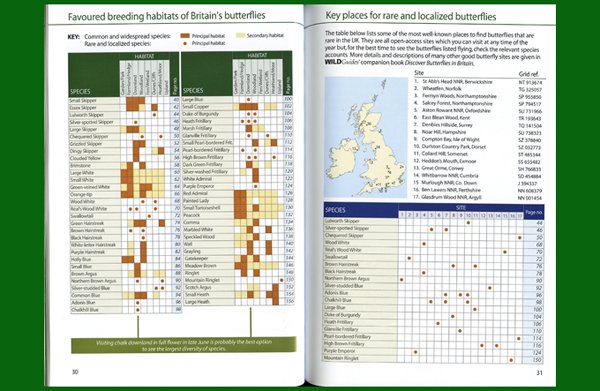

Introductory material follows the WILDGuides formula, with chapters on biology and life cycle, habitat, and principles of butterfly identification. The charts above show “favoured” breeding habitats of resident butterflies and where to find rare ones. Eggs, caterpillars, and chrysalises are depicted in a lengthy chapter following the Species Accounts. The chapter features photos of each life stage for each species, with pages numbers keyed back to the species accounts. And, although I appreciate attention to details like this, I would have preferred to view these earlier life stages within the Species Accounts. Unlike dragonflies, caterpillars and chrysalises are very important to butterfly people, especially enthusiasts engaged in butterfly gardening. And, speaking of gardening, I was very surprised not to see anything on that topic. There is, however, a great, informative chart on foodplants and nector sources for caterpillars and butterflies of each species.

David Newland and Robert Still are the main authors of Britain’s Butterflies. David Newland has been a butterfly enthusiast since boyhood, and on his website describes how a decision in 2003 to photograph all the butterflies in Britain turned into the WILDGuides book Discover Butterflies in Britain. He has more recently written a field guide to Britain’s Day-flying Moths. Robert Still is WILDGuides publishing director, an ecologist, and a butterfly and bird person. David Tomlinson and Andy Swash share author credits as well. Tomlinson wrote the first edition of Britain’s Butterflies, upon which this book was based, and Swash contributed many of the tasks integral to a quality field guide. I want to add that one of the things I like about these WILDGuides books is that credit for intellectual and task contributions are spelled out in their Acknowledgements section.

Britain’s Dragonflies and Britain’s Butterflies

Both field guides are excellent books, providing information on species identification, life cycles, and conservation that go beyond basic field guide requirements, employing up-to-date visual design and photographic content and techniques. An iPhone/iPad app for the dragonfly guide has just come out, and although I was not able to view it for this review, I am betting that it’s good. The graphic design-based content of this series makes it a perfect fit for digital platforms. Both guides, with their emphasis on readability and de-emphasis on scientific and anatomical terms, are perfect for beginning naturalists. I think intermediate and even expert dragonfly enthusiasts would enjoy using Britain’s Dragonflies. Britain’s Butterflies may be too basic for advanced butterfly enthusiasts, but it does have the advantage of being a very recent guide, incorporating the latest records and data.

I do want to point out that I started this review talking about my personal mission of identifying the dragonflies and butterflies seen on a trip to France, and how that led me to these books. I want to emphasize that these books are field guides to Britain and Ireland only, just like it says in their titles. There is overlap in the species found in Britain and Europe, and I benefited from that in my identification quest.

Several field guides on dragonflies and butterflies in Europe have been published, and I wish I had the time and money to purchase all of them. You can find their titles in the “Further Reading” sections of both books. The reasons why I haven’t bought these guides are the same reasons I ended up using field guides for Britain and Ireland to identify species seen in France. It is a lot easier to purchase titles from Princeton University Press than it is to buy foreign titles, even when using excellent online companies like Book Depository. The titles come much sooner and they are far less expensive. I am very happy that the Princeton WILDGuides series also turned out to be of such high quality. The series has some very interesting titles, including Britain’s Reptiles and Amphibians, Britain’s Orchids, Britain’s Freshwater Fishes, and Britain’s Hoverflies. I look forward to my next trip to Europe, some time in the near or far future, when I will be able to use Britain’s Dragonflies and Britain’s Butterflies once more, and maybe even some of these titles. Meanwhile, if you’ve used these or other field guides, let us know your opinions and recommendations. Remember, there is no such thing as owning only one field guide!

Thank you to Princeton University Press who graciously provided a review copy of Britain’s Butterflies.

——————————–

Britain’s Dragonflies: A Field Guide to the Damselflies and Dragonflies of Britain and Ireland (Second edition, fully revised and updated),

by Dave Smallshire & Andy Swash.

WILDGuides Ltd., 2010; distributed by Princeton University Press.

paper, 208 pp., 6 x 8 1/2, 428 color photos, 290 line illus. 66 maps.

ISBN 978-1-903657-29-4

$25.95, £17.95.

App available for iPhone and iPad, $13.99.

Britain’s Butterflies: A Field Guide to the Butterflies of Britain and Ireland (Second edition, fully revised and updated),

by David Newland & Robert Still with David Tomlinson & Andy Swash.

WILDGuides Ltd., 2010; distributed by Princeton University Press.

Paper, 224 pp., 6 x 8 1/2k 558 color photos, 10 line illus. 75 maps.

ISBN: 9781903657300

$25.95, £17.95

Thanks Donna for a thoroughly helpful review.

It seems that Princeton University Press produces many of the best field guides. I have their Birds of Europe, Birds of Mexico and central America, and Common Mosses of the northeast and Appalachians. All great field references.

Thanks Peter! I am very happy that PUP is continuing to publish and update field guides. So many university presses are cutting back these days. I think the partnership with the British WILDGuides is a great way to expand their base.