For much of its history, Portugal has sat secluded at what was long considered the very end of the known world — at least from a Western point of view. Not far from its capital Lisbon lies Cabo de Roca, the westernmost point in mainland Europe. Beyond that is the entire expanse of the Atlantic Ocean, stretching some six-hundred leagues west to Newfoundland — and even further to the mainland shores of North America. In the other direction, all of the great Eurasian landmass ranges east to the Pacific, encompassing countless cultures and languages for over six-thousand miles. But like Spain, its only neighbor on the Iberian Peninsula, Portugal is cut off from the rest of Europe by the steep, natural border formed by the Pyrenees.

Common Pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) the star of this week’s wine, as depicted in a 1918 watercolor by Scottish painter and illustrator Archibald Thorburn (1860-1935).

Seclusion, of course, can sometimes have its own advantages — Portuguese history and its distinct culture have been shaped in great part due to both its fierce sovereignty and its position on the outskirts of the Continent. But complete isolation is nearly impossible to secure: Nature, in whatever form, almost always finds a way around. And with all the unavoidable concern about infectious disease of late, and with the prospect of indefinite “social distancing” on everyone’s minds, it’s been difficult the last few days not to view even the most everyday items such terms. Even our featured wine on this week’s edition of Birds and Booze — a wine made in remote Portugal using foreign grapes and featuring a long-ago introduced bird — provides an interesting illustration of this relationship between the forces of isolation and exchange. But rather than dwelling unhappily on the inevitable spread of disease against the best-laid quarantines, let’s enjoy a glass of wine and have a look at this more agreeable proliferation of birds and grapes.

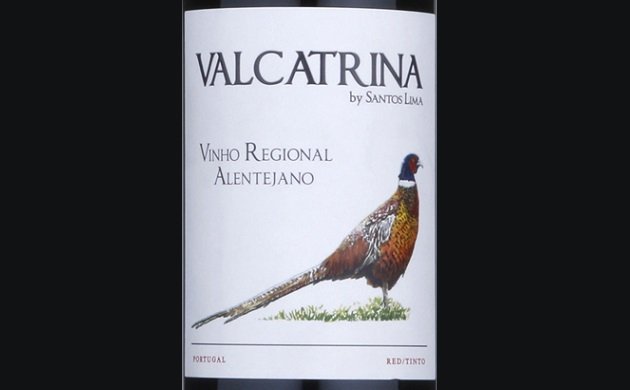

On the label of this week’s wine — the 2015 Casa Santos Lima Valcatrina from Portugal’s Alentejo region — is a Common (“Ring-necked”) Pheasant (Phasianus colchicus). One of the world’s most handsome and successfully introduced gamebirds, the Common Pheasant has been well-established for centuries — thanks to human trade — far outside of its original range in the Balkans and the foothills of the Caucasus, first in Roman times across most of Europe, and later in North America (beginning in 1773). We can’t be sure by which route pheasants first came to Portugal — either overland or by ship — but in any case, it stands to reason that this far-flung edge of the continent was one of the last places in ancient Europe to be populated by this introduced species. But like elsewhere in Europe, they’ve found a home there, even in the rugged, sun-baked terrain that dominates the Alentejo region of southeastern Portugal.

Common Pheasants (1837) (belonging to a subspecies without white neck rings, apparently) by English artist and illustrator Edward Lear (1812-1888).

Like the Common Pheasant, two of the three grape varieties used in this week’s wine were once foreigners that have now found a home in Portugal, though they had much less distance to travel to get there. The more predictable of these is the Syrah (or Shiraz) variety, famous the world over thanks to its spread not only to Portugal, but much further afield to Australia, South Africa, Argentina, and other overseas wine regions. Though its origins aren’t known with great certainty, it likely comes from France, having been long documented in the Rhône valley. The other foreign grape used in this wine is the red-fleshed Alicante Bouschet, which — though it originated in France as early as 1866 — has arguably found its true home in Portugal’s Alentejo region, where it’s been planted widely since the late nineteenth century. In fact, the Alicante Bouschet is now largely absent in its homeland. Only one of the grapes used in the Valcatrina from Casa Santos Lima is indigenous to Portugal, the much-loved Touriga Nacional, but even here its use is rather unconventional. Historically, this cultivar was used primarily in port production, but it’s recently made its presence in the Portugal’s expanding portfolio of excellent table wines, particularly among Alentejano winemakers less bound to the winemaking traditions of their northern compatriots, their neighbors just to the east in Spain, or anywhere else in Europe, for that matter. In Alentejano winemaking, isolation can sometimes inspire independence and foster indigenous traditions, even when they involve the use of “foreign” ingredients.

Alicante Bouschet grapes from L’Ampélographie: Traité général de viticulture, a seven-volume ampelography by Pierre Viala (1859-1936) and Victor Vermorel (1848-1927), published between 1901 and 1910 and illustrated by Alexis Kreyder (1839-1912) and Jules Troncy.

Blended together in the Valcatrina by Casa Santos Lima, this trio of homegrown and introduced cultivars produces a lovely, drinkable vinho regional, the Portuguese counterpart to the vins de pays (“country wines”) of France, regional wines without a varietal designation. The wine spends four months aging in French and American oak barriques, from which it emerges with an aroma of dark berries and a hint of baking spice. There’s a good dose of ripe blackberry on the palate, along with a slight snap of acidity and crisp tannins that help to rein in the robust and juicy fruitiness of this characterful Portuguese red.

Stay healthy, everyone. Good birding and happy drinking!

Casa Santos Lima: Valcatrina – Vinho Regional Alentejano (2015)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

* This week’s wine was tasted in early 2019.*

Leave a Comment