Depending on one’s perspective, it’s either through hilariously misleading irony or outright false advertising that many of the world’s great liquors derive their English names from various native words for a somewhat more wholesome liquid: water. Whisky comes from the Scots Gaelic uisge-beatha (or uisce beatha in Irish), meaning “water of life”, which is in turn a calque of the Latin aqua vitae. This older Latin phrase inspired the names for liquors in several European languages, such as eau de vie in French and akvavit in Swedish. The Russians are even more bald-faced in their deception: vodka is a direct translation of “water” – and nothing else (so what’s Russian for “water”?). And for all those liquors without an aquatic etymology, their names tend to come from a principal ingredient or process: gin after juniper (Juniperus spp.), brandy from the Dutch branden (“to burn, distill”), and mezcal from the Nahuatl mexcalli, meaning “oven-cooked agave”. And so on.

So, it just might be that pisco – the beloved South American grape brandy contentiously claimed by both Peru and Chile – is the only spirit named after birds. The name of the liquor is likely borrowed from the city of Pisco on Peru’s central coast, an important port for the pisco trade in the early days of the Spanish viceroyalty. The etymology of the city name itself is debatable, but according to the Chilean linguist Rodolfo Lenz, it comes from the Quechua pishku, meaning “bird”. Why this one city alone would be named for birds, in this country of 1,800 species, is unclear, but it could very well be a designation inspired by the nearby Islas Ballestas, an uninhabited island group just offshore from Pisco and home to enormous breeding colonies of Humboldt Penguins, Inca Terns, Peruvian Boobies, and many other species.

Pishku: Peruvian seabirds concentrate in huge numbers on the islands off the coast, as with these Peruvian Boobies I saw at the Islas Palomino near Lima.

Even though pisco has been made in Peru for several centuries, in this land famed for its ancient civilizations, it’s a relative newcomer. There’s an even more venerable pre-Columbian tradition of brewing a beer called chicha from maize (corn) that continues to this day in Peru, but cultivated grapes, winemaking, and the practice of distillation didn’t arrive there until Spanish conquest and colonization in the sixteenth century. To their delight, the Spaniards found that their domestic wine grapes of the European species Vitis vinifera grew well in Peru (the New World has only wild grape species that are generally considered ill-suited to winemaking), but in those early days, domestic cultivation was reserved mostly for the production of sacramental wine.

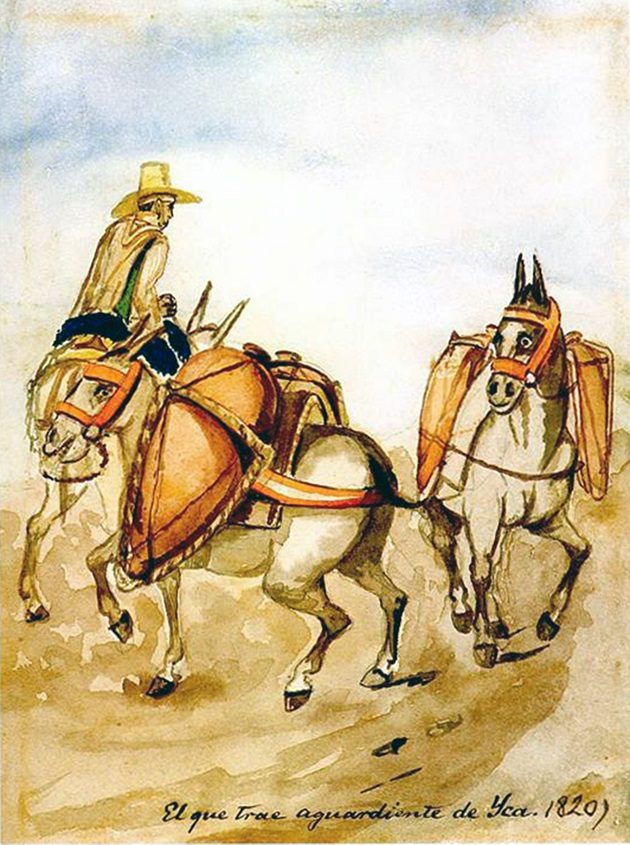

An early pisco scene in watercolor by Afro-Peruvian painter Pancho Fierro.

However, with the establishment of vineyards in the Ica valley and elsewhere on the central coast, winemaking quickly grew in Peru to such an extent that it threatened to undercut sales of wine imported from the Spanish mother country. By 1595, protective mercantilist policies ordered by the Crown banned the creation of new vineyards in Peru, along with a later prohibition on exports of Peruvian wines to other Spanish colonies.

At some point, probably by the early sixteenth century, distillation of wine into brandy also began in Peru. It may have arisen as a domestic replacement for orujo, a pomace brandy also imported from Spain (pomace being the solid portion of grape must – that is, the skins, seeds, and stems – left over from winemaking after the juice is extracted). The Spanish called (and still do) these liquors aguardiente (literally, “burning water”). Unlike orujo, however, the new Peruvian aguardiente was distilled from the wine itself, rather than the pomace. At first, this aguardiente peruano was used to fortify wine to preserve its quality (in the way that vermouth, Madeira, and Marsala are), but in time, it came to be appreciated for its own qualities and drunk on its own. As much of this aguardiente was shipped out of the port city of Pisco, it was known as aguardiente de Pisco, which was later shortened to just pisco.

Over the years, the fortunes of pisco have risen and fallen: a massive earthquake devastated many of the cities and cellars associated with Peruvian wine and pisco production in 1687, and in the 1800s, many vineyards were converted to more lucrative cotton farms, especially when the American Civil War caused the price of imported cotton to skyrocket. But pisco persisted through these hardships and even spread north up the Pacific coast of the Americas, becoming especially fashionable in the late-nineteenth century saloons of San Francisco and Gold Rush California.

Today, the spirit is beloved by Peruvians and its production is guarded by their government, which has established five official denominations of origin, all located along the Pacific coast: Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua, and Tacna. Modern pisqueros in these regions still practice age-old methods, distilling pisco in small batches in traditional copper pot stills. The handmade stills come in two forms: the gourd-shaped alembique (alembic) or a flat-top falca, the latter of which is usually made with a small portion of gold mixed into the copper.

After distillation, Peruvian pisco is aged for at least three months. Unlike brandy, whisky, and other darker spirits aged in wooden barrels, pisco undergoes its brief maturation in vessels that impart no color or flavor to the finished product, a method which allows the delicate flavors and aromas of the traditional grapes permitted in pisco distillation – Quebranta, Negra Criolla, Uvina, Mollar, Moscatel, Torontel, Italia and Albilla – to be preserved above all other characteristics. Today, this typically takes place in glass or stainless-steel vessels, but long ago, tall clay amphorae known as botijas served this purpose. Pisco comes in three principal forms: a puro a made from single-varietal grapes, acholado made from a blend of grape varieties, and mosto verde, a version sweetened with residual sugars left over from incomplete fermentation of the grape must.

Despite its growing popularity abroad, I waited until I traveled to Peru two months ago for my first taste of pisco. Anyone who’s been to Peru – as many lucky birders doubtlessly have – can’t fail to notice the ubiquity of the drink, especially in and around the sprawling capital Lima.

Pisco’s most famous use, of course, is in the namesake cocktail, the pisco sour. Though it’s not the first recorded pisco cocktail, it’s by far the most well-known (a pisco punch calling for gum arabic, among other ingredients, was invented in San Francisco in the nineteenth century and there were surely earlier mixtures now lost to history). The classic Peruvian recipe – allegedly first concocted in Lima by an American bartender named Victor Vaughen Morris in the early 1920s – is really a South American take on the American whisky sour, and calls for pisco, lime juice, simple syrup, ice, egg whites, and bitters. Aficionados maintain that only Chuncho bitters – a tincture of thirty peels, herbs, roots, barks, and flowers from the Amazon – should flavor a true Peruvian pisco sour, but there’s no shame in substituting the more commonly available Angostura or orange bitters.

I had my very first pisco sour at a restaurant in Cusco after a long and exhausting day of sightseeing in the city the Incas called “the navel of the world”. My final pisco sour of the trip, which was no less restorative, was enjoyed on the balcony of the historic Gran Hotel Bolívar in Lima around midnight, sipped comfortably over the hustle and bustle of late-night traffic in the Plaza San Martín below, mere hours before boarding my flight back home. This grand dame of limeño hotels still serves up what is considered the classic pisco sour – and it can even be ordered as an indulgent double portion dubbed the La Catedral that features a whopping five-ounce pour of pisco. No wonder the hotel bar and its prodigiously poured pisco were favorites of Ernest Hemingway and Orson Welles – not exactly icons of temperance. While my appetites are generally more modest than theirs, I felt it was only appropriate to follow suit and cap this inaugural trip to Peru with a cathedral-sized pisco sour of my own.

My very first pisco sour, as served at Peruvian chef Gaston Acurio’s Chicha in Cusco.

There’s a good chance I was still under the influence of La Catedral as I perused the duty-free shop at Jorge Chávez International Airport later that night. Certainly, I had only one souvenir in mind: a bottle of pisco. I snatched up the very first one I found, not out of haste or desperation, but because it had an illustration of an Andean Condor on the bottle canister. Having dipped on this species just a few days earlier in the Cusco highlands, I was determined to return home with a least one memento of this iconic vulture of the high Andes.

It wasn’t until I got home that I noticed a second bird on the bottle: Cepas de Loro, the distillery that crafted my keepsake pisco, means “vines of the parrot”. Owner Cesar Uyen chose a playful hieroglyphic-like image of a parrot for the brand’s logo, which came from a nearby pre-Incan rock art carving in Pitis. The destilería is in the small town of Mesana in the department of Arequipa in southern Peru, along the Río Camaná, with vineyards in the nearby Valle de Majes.

The bottle I chose in the shop – solely on account of the condor on it – was the Pisco Puro Muscatel, one of several styles made by Cepas de Loro. This is a single-varietal pisco made with Muscat grapes, a family with an unfortunate reputation – at least in the United States – for its use in cheap, illicit plonk during Prohibition. There are over two hundred varieties of Muscat grapes, however, a diversity that suggests that it is one of the oldest domesticated strains of Vitis vinifera – if not the oldest – with a lineage that likely stretches back to antiquity. Muscat grapes are known for their sweet, floral aroma, and still play an important role in several esteemed European wine styles. The fragrant, aromatic qualities of Muscat grapes also contribute to an excellent pisco.

While it’s tempting to turn all piscos into sours, single-varietal piscos demand to be savored without distracting accompaniment to appreciate their delicate aromas. Alone in the glass, Pisco Puro Muscatel from Cepas de Loro is luminously clear, with an initial impression of mint, lavender, and citronella. The tangerine and lemongrass bouquet leads into flavors of wine grapes and honeysuckle, with a clean, herbal finish. It’s a complex nip on its own, surely, but these are qualities that won’t be wholly lost in a cocktail, either.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Cepas de Loro: Pisco Puro Muscatel

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Leave a Comment