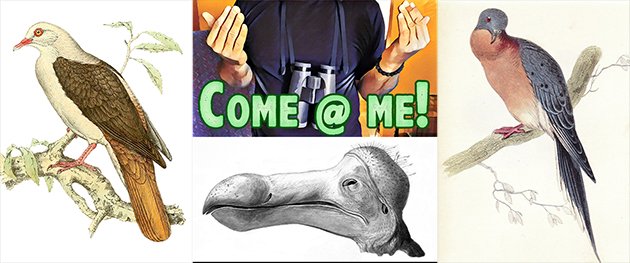

It was the Pink Pigeons (Nesoenas mayeri) that got me thinking. Pink Pigeons were featured on episode four of the second season of The Zoo, the excellent television series about The Bronx Zoo,* and their story was disturbing. Basically, this species is so dimwitted, it doesn’t know how to survive.

The Zoo episode focuses on two Pink Pigeon couples: The Stud and Serendipity, a male and female that the zoo people hope will mate and produce a viable egg, and Thelma and Louise, a same-sex pair-bonded couple who the zoo people hope will incubate the egg and nurture the chick. Because, Pink Pigeons are not capable of doing the tasks required to create and bring up children of the species. Senior zoo keeper Alana O’Sullivan openly admits this, “It seems like they’re either really good at courtship and fertilized eggs or they’re really good at sitting on the eggs, but they can’t be good at everything.” This description appears to be an overstatement though, because we learn by the end of the episode that The Stud and Serendipity have not produced one viable egg. (And, The Stud only produced one last year before being sent to time out for sexual harassment. He is the Harvey Weinstein of Pink Pigeons).

Pink pigeon near Le Pétrin, Mauritius by Michael Hanselmann, used under Creative Commons license

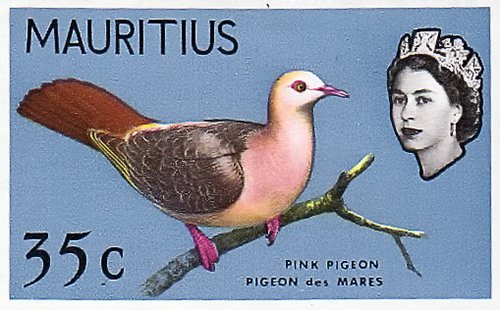

A bit of background: Pink Pigeons are medium-sized, pink/gray/ brown birds found on the island of Mauritius, Indian Ocean, east of Madagascar. (Mauritius may sound familiar, it was also the home of one of our most famous extinct birds—the Dodo. More about the Dodo in a minute.) Pink Pigeons were once found throughout Mauritius, but by the 19th century the population became fragmented and by 1986 only 12 or 16 pigeons remained, depending on your source of information, less than 12 by 1991. The causes were the usual reasons for island extinction—deforestation by both humans and invasive plants that crowded out native plants, hunting, and invasive rats, mongoose, monkeys, and, of course, feral cats. Nonprofit organizations, science, and the best intentions in the world came to the rescue with a captive breeding program, and we now have over 400 Pink Pigeons living in Mauritius, the nearby island of Ile aux Aigrettes, and the zoos hosting the breeding program, including the Bronx Zoo.

Meanwhile, on The Zoo, the keepers have been creating an environment for Thelma and Louise so they can nurture the hoped-for egg from The Stud and Serendipity. They hang baskets to be used as nests and fill the room with soft nesting materials. Because, Ms. O’Sullivan says, “I cannot trust the Pink Pigeons to build their own nest. They’re just not the greatest architects. You know, the male will take a stick and the female will take a stick and they’ll put them together and then they’ll lay an egg, and that doesn’t bode well for the egg. So, we always say that the Pink Pigeon approach to nest building is two sticks and a prayer.” Seriously? These endangered birds have trouble producing a fertilized egg and, even worse, they don’t even know how to build a nest so the egg survives?

And, as we find out in a blogged coda to the episode, they can’t even take care of their eggs. On the WCS web page, Ms. O’Sullivan informs us that a fertile egg is finally produced (not clear if it’s from The Stud or the other male, the Bronx Zoo only has two males) and abandoned and successfully nurtured by a pair of Ring-necked Doves. What happened to Thelma and Louise? Or any of the other female Pink Pigeons (there are 8!)? Don’t these birds care about propagating their species? As Ms. O’Sullivan warns us at the beginning of the episode, “They are NOT the brightest birds at all.”

Is it any wonder that Pink Pigeons were on the brink of extinction when humans intervened? Maybe these birds, as attractive as they appear with their pinkness and cluelessness, belong on the extinct list.

I know, that’s harsh. I don’t like talking about the end of a species like it’s a good thing (I mean, when you’re gone, you’re gone). But, in the larger sense, if the members of a species cannot take care of themselves, if they cannot copulate and fertilize and create decent nests and take care of their young, then haven’t they reached a dead end on the evolutionary tree?

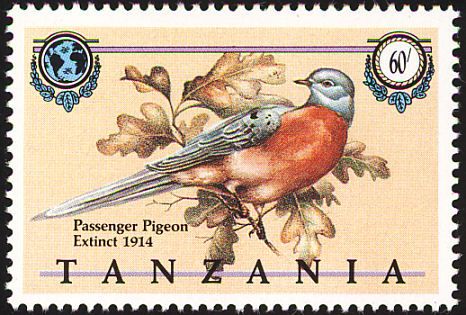

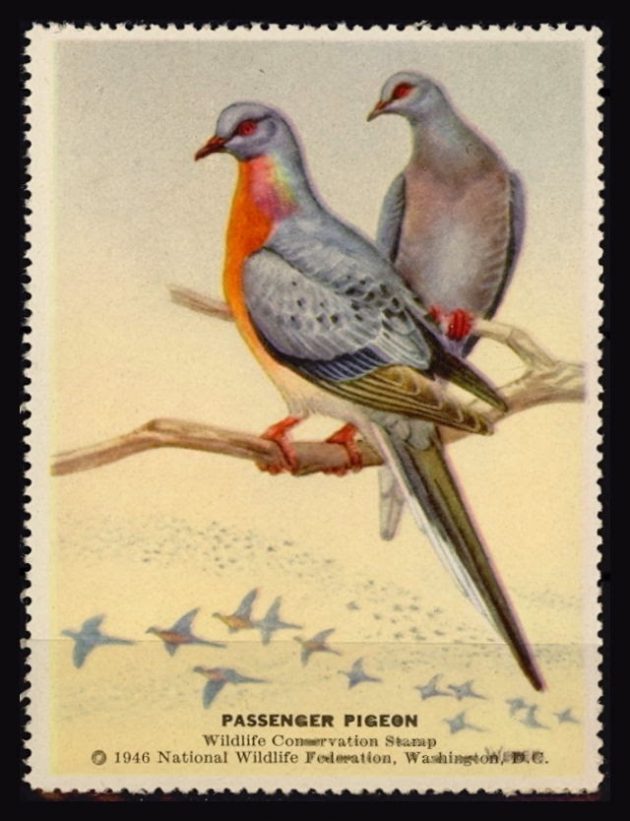

Let’s take this thought–that some birds should be extinct–and apply it to some actual extinct birds. Passenger Pigeons, for example. The conservation and birding world, including 10,000 Birds, went into mourning back in 2014, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the death of Martha, the last of the Passenger Pigeons. These fabled birds that once filled the skies for days as they migrated over the Midwest. Naturalists wrote books–many books, children and artists created murals and sculptures, museum curators exhibited specimens, editorial writers and bloggers alike cried over man’s greediness and heedlessness.

Yet, think a bit about what our world would be like if the Passenger Pigeon still existed. These were not birds that could live in small groups; it is postulated that their numbers quickly declined once hunting reduced the size of the flocks below a critical mass. We know what those large flocks were like. In A Feathered River Across the Sky, Joel Greenberg quotes the experience of the residents of Columbus, Ohio in 1855: “Now everyone was out of the houses and stores, looking apprehensively at the growing cloud, which was blotting out the rays of the sun. Children screamed and ran for home. Women gathered their long skirts and hurried for the shelter of stores. Horses bolted. ….Day was turned to dusk. The thunder of wings made shouting necessary for human communication” (p.54). Forests where they roosted were left bare, broken limbs and trees bent out of shape from their weight, hundreds of pigeons roosting on top of pigeons. And, then there were the droppings. A foot deep by some accounts, it killed what life was left in the forest. Fires would erupt after the pigeons came through. And, I’m sure the smell was not wonderful.

Is this the type of bird behavior that makes sense in our world? Is this the type of avian experience we want? First of all, airplane pilots and flight controllers would go nuts. They have a hard enough time with Canada Geese. Second, we want children to enjoy observing birds, not running and screaming like a scene from a Hitchcock movie. Third, that is just an awful lot of excrement. EPA has enough troubles without having to cope with the toxic effects of ginormous amounts of crap. As Jonathan Rosen says in his article on Passenger Pigeons and Greenberg’s book, to picture the Passenger Pigeon in a world of humans is to picture “the clash of two irreconcilable species with gargantuan needs.” You just can’t have both.

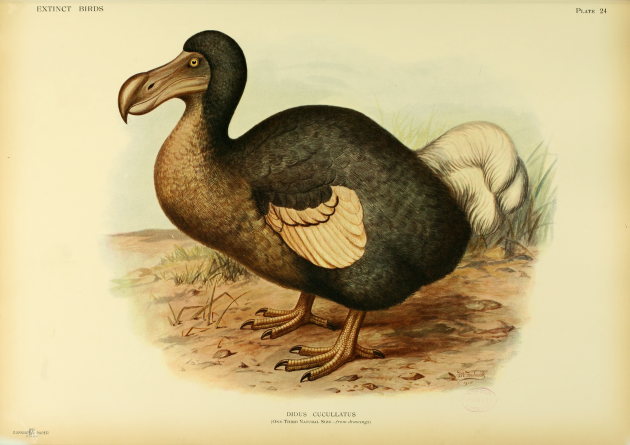

To look at this question from another viewpoint, think of the Dodo. Another inhabitant of the island of Mauritius, the Dodo was a flightless, very large bird that we don’t really know a lot about because it was quickly gone before it could be studied. We’re not even sure what it looked like. The depiction of the Dodo as a very round, clumsy creature has been disputed by scientists, who say it was only round because captive Dodos were overfed. The only drawings we have of the Dodo that we know for sure were based on live birds on Mauritius show a bird with a round torso but more upright and active.

So, why not mourn the Dodo and its inability to withstand sailors’ appetites (though many accounts say it really didn’t taste that good and research indicates the percentage of Dodos hunted and killed was relatively small), non-native predators, and the capricious ecosystem of its own island? Because, it has been much more valuable as a cultural icon, a symbol of whimsey and extinction. What would Alice in Wonderland be without the Dodo proposing and then running the ‘Caucus-race’? The caucus-race is, as Lewis Carroll fans know, a race run in a sort of circle with no beginning and no end, people coming and going as they please, in other words, a satiric depiction of politics. Charles Dodgson is said to have identified with the Dodo, an idea given credibility by the way the other Wonderland creatures mock his erudite form of speech.

And, where would we be without the term “Dead as a Dodo”? The Dodo, with it’s clownish appearance and well-known tragic end, is the most effective symbol of extinction we have. It’s name attached to conservation fundraising pleas needs no explanation, saving public relations specialists and speechwriters hours of time and enabling us, supporters and funders of conservation, to support conservation without guilt (I mean, the bird went extinct a long time ago so, no complicity on our part). We really are better off with extinct Dodos.

Finally, when mourning extinct birds, we need to remember that dinosaurs were birds, or, rather, closely connected to birds. You’re read or seen Jurassic Park, right? (No need to see the film sequels, though I’m partial to the one with Jeff Goldblum, not the current film, the second sequel.) Do I need to write anything more about the dire consequences of having breathing dinosaurs amongst us? This is what the Yi qi dinosaur, whose specimen was found almost totally covered with feathers, is thought to have looked like. It was a small dinosaur. Since the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park are not scientifically correct, let’s imagine what they all may have looked like with their feathers, living in today’s world.

Restoration of the Yi qi dinosaur from the late Jurassic era, China, by Emily Willoughby, used under Creative Commons license.

Now, I don’t think we shouldn’t mourn for all extinct birds. I would dearly love to see an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and I think our Carrie deserves to observe a Great Auk. Bachman’s Warblers were seen so infrequently that they are probably known more for being extinct than as an integral part of the ecology of the southern United States and Cuba, but it would be interesting to still have them around. They would be one of those birds that listers spend years wishing to see, and birding tour companies would have specialized tours focused on finding the elusive songbird.

But, I do think that some birds are extinct (or should be extinct) because their time has come and gone. And, though we should still value them, and read about them, it is a waste of our energies to mourn them, to feel guilt and regret. And, possibly, a waste of resources to try to extend near-extinct species into the future. Don’t cry for extinct birds, oh birders! Celebrate the ones who live and who can make their own nests!

* If you are a cable subscriber, you can view this episode and others on the Animal Planet website.

*****

Come@Me Week is a cheap ploy ginned up by some high priced consultants we at 10,000 Birds hired and then stiffed on the bill. We’re desperately trying to stay relevant in a bird blogosphere being decimated by Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and memes. We here at 10,000 Birds have no shame and it was either this or lots of posts about woodcocks, boobies, and woodpeckers. All the posts in Come@Me Week are probably the opinions of the authors of said posts and no one else. Well, except maybe you. Weirdo. Agree? Disagree? We’ll see you in the comments. Or, more likely, on Facebook. Sigh…

I’d kill to see the Elephant Bird, or Moas (there were 9 species), or any of Terror Birds (although they’d, more likely, kill me).

Dragan, yeah, what we really need are some Terror Birds–“feathers, T-rex-like feet, and a hooked beak that could sever the spinal cord of a horse with one blow” (BBC Earth website). We don’t want to die from our birds!

Whither the Whooping Crane?