Following passage of the United States Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) was among the first 75 species listed for protection, the so-called “Class of 1967”. Beset by poaching by cattle ranchers, habitat loss, DDT, and lead poisoning (from consuming shotgun pellets embedded in the condor’s carrion fare), populations of this enormous New World vulture fell into a serious decline in the twentieth century. In 1987, only 27 were left in the wild and drastic action was taken to save the species: all remaining birds were captured, the California Condor was declared extinct in the wild, and a captive breeding program was begun, initially carried out by the San Diego Wild Animal Park and the Los Angeles Zoo.

After a slow start, enough chicks had been hatched and raised by 1991 to allow for the release of captive-bred condors in the wild in California. Reintroduction efforts expanded to Arizona in 1996, and later, to the Baja California peninsula in Mexico.

By any measure, the recovery of the California Condor has been a remarkable success. Its population, which once numbered as few as 22 individuals, had climbed to 446 birds by the end of 2016, with 276 of those birds flying free in the wild.

I was fortunate enough to see these birds myself on a trip to the Grand Canyon a few years ago, not long after I began birding. They’re becoming an expected sight there – and one that’s hard to miss given their immense size. More remarkable still was the recent appearance of a California Condor in Idaho, a first for that state since recovery programs began and a hopeful indication of further range expansion.

A California Condor soaring over the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

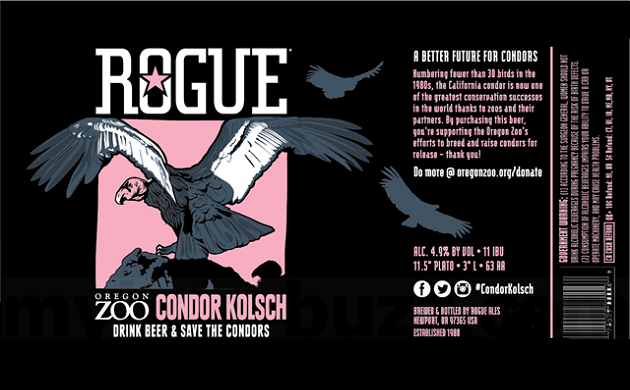

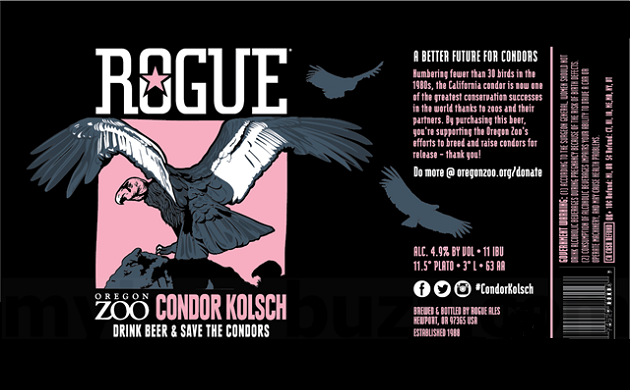

This week’s beer is named for these remarkable vultures: Condor Kolsch from Rogue Ale & Spirits of Newport, Oregon. The first part of that name is easy enough for birders, but that second word – properly rendered in German as Kölsch – requires some explanation for all but the most dedicated beer drinkers. Beer styles occasionally face extinction, too, though their revival is more often of greater certainty, especially in these days of inspired brewers mining dusty old brewing logs for a taste of the past. While never in any real danger of fading away, Kölsch, a pale beer indigenous to the German city of Cologne, has never been very well-known outside of its home in the Rhineland.

Part of its obscurity is due to the fiercely protective relationship Cologne has with its beer. Kölsch has enjoyed special trade status in the European Union since 1997 as a product of protected geographical indication (PGI), the only beer in the world with such an appellation controlee-style designation. At least where these laws apply, no beer may call itself Kölsch unless it is brewed within 50 kilometers of Cologne and to strictly defined specifications.

So, what is Kölsch, then? Though it’s been made by dozens of independent brewers in Cologne for a century or so, enough similarities exist from brand to brand to constitute a legal definition, though there is certainly plenty of room for individuality as well. Kölsch is a very pale, lightly-hopped beer fermented warm with top-fermenting yeast, and then cold-conditioned or lagered for a time. It’s often called an “ale” by English speakers, a forgivably convenient but incorrect comparison that smacks of facile Anglocentrism: the Germans refer to it – with all due precision (and rather commendable restraint with the use of a single compound noun) – as an Obergäriges Lagerbier, or “top-fermented lager beer”.

Top-fermented beers were the standard practice in many parts of Germany in the nineteenth century when the first truly pale lager was brewed in 1842 in Pilsen, the Czech city that gave its name to the beer that went on to conquer the world. In the ensuing years, the enormous popularity of Pilsner – driven in part by the introduction of glassware that showed off the novelty of crystal-clear, golden beer – caused brewers across Europe to respond with paler concoctions of their own. Cologne brewers too were won over by the lightly-kilned pale malt that give Pilsner its famous straw hue, but they clung steadfastly to their house yeast strains and top-fermenting ways, and in the alchemical combination of these elements, Kölsch was born. Along with the Altbier of nearby Düsseldorf and a few other examples, Kölsch today continues as a vestige of Rhineland brewing, holding out against the international sameness of cold-fermented lager styles.

Kölsch bears a superficial resemblance to Pilsner, with which it was originally brewed to compete, but it’s softer, rounder, and more gently hopped, and thanks to its warm fermentation, it often offers subtly fruity, even wine-like notes entirely unheard of in lagers. It’s less bubbly too, calmer and less assertive, making it a more accommodating partner to food, and especially lovely for warm-weather drinking.

It comes as no surprise that the people of Cologne are steadfastly devoted to their peculiar native beer, which also shares a name with the Rhineland dialect spoken here. It’s often said that Kölsch is the only language that one can also drink.

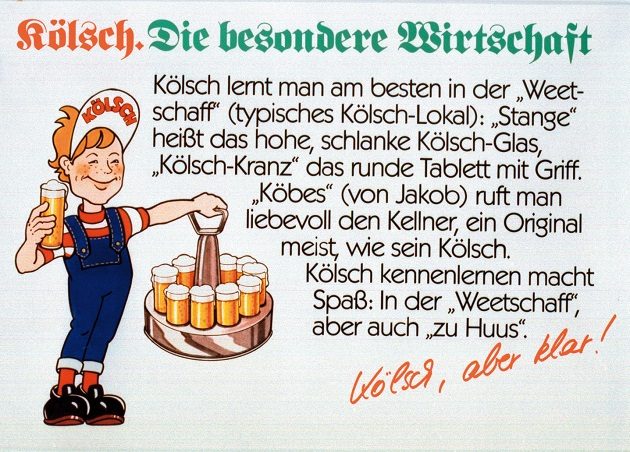

This civic pride extends to the customs of serving Kölsch in Cologne as well, where tradition dictates that it be served in a distinctively thin, brittle-looking tube of glassware called a Stange, meaning “stick” in the dialect of the city. These Stangen are loaded by the dozen onto round, handled serving trays in a circular arrangement called known as a Kranz (“wreath”), and hastily ferried to drinkers by Köbesse (“Jacobs”), as the café waiters of Cologne beer cafes are called.

Except for the overalls, this vintage advertisement by the Gaffel brewery illustrates all the trappings of Kölsch service in Cologne.

By tradition, the Köbe is always a man, though this isn’t a legal requirement. His curious title originates from Cologne’s position as a popular rest along the medieval pilgrim road to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the alleged burial site of Saint James the Greater. Itinerant work was a common way to earn money for the long journey to Finisterre, and after a time, wayfaring servants in Cologne came to be known as “Jacobs”, a cognate of the name James. Traditionally, Köbesse were identified by their knitted blue waistcoats, though these days the uniform is more likely to be a jacket or shirt of the same shade.

If the clunky steins swinging and clinking in the beer halls of Munich are obligatory devices in scenes of beer-soaked gluttony that unfairly represent Germany to much of the world, the slender, dainty Stange of Cologne is a vessel of more restrained and unexpected elegance – though its form follows a function dictated by volume as well. Usually calibrated at a mere two centiliters, a Stange can be drained in short order by even the most temperate drinkers before the Kölsch goes warm and flatg. Because of this, the glasses require frequent replenishment by the attentive Köbesse of Cologne. To keep it from becoming too filling over the course of several rounds, Kölsch is conditioned with a characteristically soft level of carbonation, and a modest serving ensures that the beer remains cool and refreshing, with a steady stream of gentle bubbles trickling upwards, down to the very last sip of each glass. With enough room for another, of course.

So, after bearing with that admittedly lengthy lecture on Cologne and its beer, let’s return to the condor.

With a double-headed eagle on its coat-of-arms, Cologne has a longstanding penchant for ominous-looking raptors.

Rogue brewed Condor Kolsch to support California Condor conservation efforts in partnership with the Oregon Zoo of Portland, which became the fourth condor captive breeding program in the country in 2003. A portion of all draft and bottle sales of Condor Kolsch will be donated to these programs. California Condors once ranged over the skies of the Pacific Northwest, where they were seen (and shot) by the Lewis and Clark expedition, and both zoo and brewery are hoping that they’ll cross the border to make a return to Oregon someday (click the link for a 2017 BirdWatching magazine article about this exciting possibility by 10,000 Birds beat writer Jason Crotty).

An out-of-range Kölsch from the Pacific Northwest. This American brewery may roguishly skirt European Union product protections by dispensing with the umlaut over the “o”, but otherwise, it’s true to style.

In the absence of a more obvious answer, I suspect Rogue chose the Kölsch style for its condor conservation beer for reasons that are purely alliterative. True, the brewery might have achieved the same effect by releasing a California Common beer, a style best represented by San Francisco’s legendary Anchor Steam, but perhaps Beaver State pride quashed this suggestion. Besides, wouldn’t “Condor California Common” be a rather crass or at least confusing name for a beer inspired by a bird that’s so famously anything but common?

Instead, I like to think that Rogue brewed a Kölsch to cast some much-deserved attention on an underappreciated beer style, allowing their Condor Kolsch to perform altruistic double-duty as a conservation effort for both birds and beer. Whatever their reasons, it’s always nice to see a good Kölsch-style beer brewed by American craft brewers. Kolsch is a sometimes misunderstood and underappreciated style. As a subtle expression of delicate malt and hop flavors, Kölsch is the antithesis of the bold, over-the-top brews that are the stock-in-trade of American craft brewers. It’s also a notoriously unforgiving style to make well: restrained and subtle, with none of the brash hop flavors or a kick of booze many craft brews can so often hide behind. This may explain the reluctance of many American brewers to make it (though it’s sometimes made and released in disguise, particularly in warm weather, with more marketable names like “summer ale” or “golden ale”).

At four centiliters, this Kölner Stange is twice the volume of the standard-issue glass in Cologne, but it still appears to be kosher for Kölsch consumption. Besides, the outsized volume seems approprate for containing a beer named for North America’s largest landbird.

Poured into the properly narrow glassware, Condor Kolsch shines in brilliant, pale gold, capped with a thick, fluffy mousse. The fine carbonation is perhaps a bit lively for the style, but these little bubbles persist in holding aloft the impressively rocky, pearl-white head, before it gradually subsides into a sudsy ring of foam around the glass. There’s a surprisingly big aroma for such a refined, delicate beer, with bright and ripe pear, floral touches of honey, a malty, almost marshmallow-like sweetness dominating, countered by slightly sulfurous notes of must and an earthy, hay-like dryness. The light and crisp palate is mildly peppery at first, followed by a grainy cereal sweetness in the middle, giving way to a soft and fruity suggestions of Chardonnay. Condor Kolsch finishes dry and subtly bitter with a note of grassy hops, but its memorably soft, malty sweetness lingers long after every sip.

Condor Kölsch is available on draft at the Oregon Zoo and at Rogue pubs, as well on sale in 22-ounce bottles in Oregon – that’s enough to fill three two-centiliter Stangen, with a little left over.

Good birding and happy drinking!

My most sincere thanks go to fellow 10,000 Birds beat writer Jason Crotty for not only bringing Condor Kolsch to my attention, but for generously procuring and shipping me a bottle from the other side of the continent. Prost, Jason!

Rogue Ales & Spirits: Condor Kolsch

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Wow, I learned a lot, exceptional post. And, good to see 10,000 Birds writers working together on two important issues–beer and conversation!

Thanks, Donna! I especially appreciate your comments on these. And I too appreciate the 10,000 Birds solidarity!