You gotta love Cuckoos. Not just the Common Cuckoo or the Yellow-billed Cuckoo, you must love the whole family Cuculidae, all 32 general and 148 species of them, from Anis to Roadrunners to Coucals to Lizard Cuckoos to Koels to Malkohas to Drongo-Cuckoos to Hawk-Cuckoos.* Each one is striking looking, though not always in the same way, some with a prehistoric look, others like they stepped out of a lizard’s den or hawk eyrie. Their feet are zygodactyl (two toes out two toes in, like woodpeckers and parrots), and their behavior is the stuff of dreams, nightmares, and cartoons. Which are probably why Cuckoos are engrained in our culture in distinct and memorable ways. In Cuckoo, a slim, very enjoyable title by Cynthia Chris, the folklore, and cultural associations we’ve developed with the birds of the Cuckoo family (mostly the Common Cuckoo), are listed, described, discussed and illustrated. There is also a natural history component, an appreciation of the birds themselves. It’s an informative, fun read, a nice break from field guides and more scientific treatises, with the possibly dangerous side effect (to one’s wallet) of motivating the reader to start planning how to see more members of family Cuculidae.

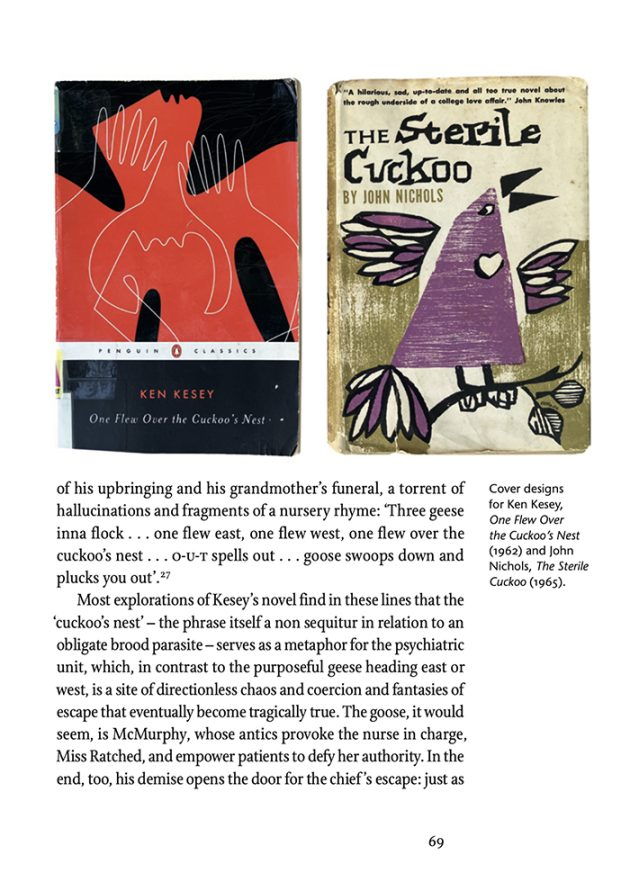

© Cynthia Chris 2024, p. 69, Cover designs for Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) and John Nichols, The Sterile Cuckoo (1965). Both books were made into award-winning films.

Before I started birding, if you asked me about cuckoos my immediate reaction would be to think of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the 1962 novel by Ken Kesey (made into a show and then a memorable film, also one of the most banned books in the U.S.). Then maybe I’d remember the 1950’s science fiction classic, The Midwich Cuckoos by John Wyndham (translated into several films, radio shows, and a television series, some with different titles). And, if I was in the mood, I might start singing a cartoon jingle of my youth about a cereal I never ate, probably because the commercial itself, featuring a screeching bird that I guess was supposed to be a cuckoo, was so obnoxious: “I’m cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs.” These are some of the ways cuckoos have made their way into our popular culture: metaphors for insanity or oddness, a word for misplaced, strange children (those are the Midwich Cuckoos, alien children born from human women).

There are more elevated references to cuckoos. Vivaldi, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Beethoven are just a few of the musicians who incorporated the Common Cuckoo’s song into their music, usually as a harbinger of spring (it seems like the Common Cuckoo holds a similar position in Great Britain and Europe as the Eastern Phoebe does in eastern North America). Aristophanes, Chaucer, and Shakespeare all wrote about cuckoos. Aristophanes may have started the use of “cuckoo” as a term for foolish fantasy with his play The Birds, where the birds build a ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land,’ a term that continues to this day in rock music, novels, and The Lego Movie. Chaucer and Shakespeare sometimes incorporated cuckoos into their tales and plays as harbingers of spring, but more often the cuckoo connection lies in their use of the ‘cuckold’ figure, a man whose wife is sexually unfaithful (or, more often in these stories, a man who suspects his wife has been unfaithful). It’s an odd linguistic turn, deriving “cuckold” from “cuckoo,” rooted no doubt in the Common Cuckoo’s obligate brood parasitism, but not really an exact parallel situation. Still, the connection is there, in literature, historical cartoons, and in modern linguistic politically oriented twists.

Chris elegantly writes about these and other ‘cuckoo’ topics. A professor of media culture at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York, she has researched these topics thoroughly (notes at the back of the book document a wide range of sources) and understands how to present a large body of facts and ideas selectively and entertainingly. The book is divided into six chapters, the first and last about Cuckoos as a bird species and family, the mid four about cultural associations: cuckoldry, madness, seasonality, and song. I found both the expected (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; Sonny, the Cocoa Puffs animated cuckoo) and the unexpected.

Making cuckoo clocks, Tryberg, in the Black Forest, c. 1915, Germany, stereograph image from the Library of Congress digital collection, https://www.loc.gov/resource/stereo.1s24762/ One of these images is reproduced in Cuckoo to illustrate its section on the pre-World War II cuckoo clock industry.

The chapter on seasonality, “Nature’s Timekeeper,” for example, starts with how much Brits look forward to hearing the Common Cuckoo’s call in spring, expressed by Wordsworth poem “To the Cuckoo” (expected), and then veers into the bird’s widespread migration from Great Britain to Africa and Asia and how it is being tracked by the British Trust for Ornithology’s Cuckoo Tracking Project (expected and hoped for), and then Chris swerves right into cuckoo clocks! I really never made the connection between Cuckoos and cuckoo clocks, maybe because I’ve had limited exposure to them. Chris describes in detail how the Black Forest cuckoo clocks were originally made, a system of weights, levers, a pendulum, and bellows encased in a carved box. Why a Cuckoo, why not a crow or a rooster? One clockmaker explains that the call of the Common Cuckoo is simple, easy to duplicate. She goes seamlessly from pre-World War II cuckoo clock industry to cuckoo clock museums to images of cuckoo clocks in children’s books with a side trip to a mention of the cuckoo in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (in this case, the cuckoo refers to Heathcliff, the misplaced child). All very unexpected.

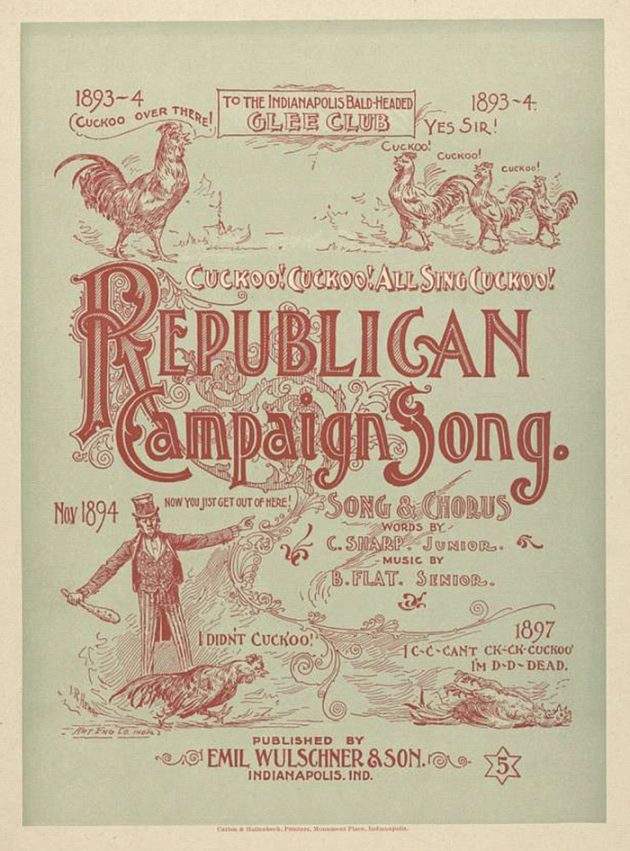

Cuckoo! Cuckoo! All Sing Cuckoo! Republican Campaign Song sheet music, 1915, public domain, https://picryl.com/media/cuckoo-cuckoo-all-sing-cuckoo; Reproduced in Cuckoo (the book).

One of the joys of reading Cuckoo are the illustrations, which are numerous and complementary to the text. (I was sent a pre-publication PDF of the book, not a printed copy, so I can only imagine how the illustrations appear in print. On my iPad screen, they are fabulous.) In addition to photographs of Cuckoo species, the book presents photos of artifacts like the book covers above, photos of cuckoo eggs and skins in museums, musical scores (most amusingly, a Republican campaign song from 1894 aimed at ridiculing President Grover Cleveland with the words, “Cuckoo! Cuckoo! All Sing Cuckoo!”), some historical photos, and many different types of artwork. I particularly like the Japanese wood cuts, which in addition to being lovely add diversity to content that is mostly Western European/American. A lot of work clearly went into sourcing these illustrations; even the public domain images are from not always easy to find sources. (Sadly, my preprint PDF does not include the contents of the “Photo Acknowledgements” section so I can’t be more specific, though the more general Acknowledgements section includes some of the artists and organizations.)

© Cynthia Chris 2024 p. 125 Katsushika Hokusai, Cuckoo and Azaleas, 1829–39, colour woodblock print. (This print can be found in many formats–poster, pocketbook–often without attribution.)

Most of the non-Western European/American material is in the “Myth and Madness” chapter, which charts how Cuckoos show up in myths and folk tales around the world, from the Greek goddess Hera (the cuckoo is one of her symbols, maybe because Zeus seduced her in that guise); to China, where cuckoo has multiple meanings; to a Bhutanese folk tale in which a male cuckoo and a female pigeon marry and have a family; to India, where the Jacobin cuckoo is a symbol of pure love; to Japanese folk tales and art. Strangely, the chapter does not include Greater Roadrunner, noted for its deep connection to the Anasazi Indians of the American southwest, nor Asian Koel, Senegal Coucal, or Greater Coucal, all of whom are part of the folklore and literature of peoples in India and Africa .** Roadrunners, Koels, and Coucals are mentioned in “What is a Cuckoo,” the book’s first chapter, in which Chris goes through all five Cuckoo subfamilies, and in the last chapter, which addresses the future of all species, particularly those considered threatened and endangered. I can only imagine that the overflowing scope of the subject outran the page limits set by the publisher.

Cuckoo is part of the “Animal” series from Reaktion Books, an independent publisher based in London, England. I’m not sure how the series has escaped my notice till now (though looking back, I see that Carrie reviewed their book on sparrows in 2013); they’ve published 98 titles since 2003, 21 of them on birds (others range from mammals to fish to insects), all focusing on the cultural and natural history of the subject animal in 200 pages or less, all copiously illustrated. I imagine that, like Cuckoo, these books are starting points, with references and resources to help the reader advance further if that is their inclination.

Cuckoo’s resources include 13 pages of References; a Select Bibliography (which includes my favorite book about cuckoos, Nick Davies’ Cuckoo: Cheating by Nature (2015) and a blog post by NYC birder and friend Tim Healy, A Tale of Two Cuckoos); a list of Associations and Websites (ranging from a website on African Cuckoo research to one on The Birds of Shakespeare); a short list of Media; and, to my joy, a Timeline of Cuckoos! You gotta love a book with an illustrated timeline. More importantly, I very much enjoyed reading about how Cuckoos, especially that paragon of obligate brood parasitism, the Common Cuckoo, have impacted human imagination and creativity across the spectrum, from pop culture to commercialism to the intellectual. I’ll never look at a Cuckoo (or Ani or Roadrunner or Coucal….) the same again.

© 2020, Donna L. Schulman, Common Cuckoo. This photo NOT in book, it’s mine, from one of my favorite twitches, to see the Common Cuckoo of Snake Den Farm, Rhode Island, November 2020.

* This count is of living species, based on IOC 14.1 taxonomy. Clement’s taxonomy (used by eBird) lists 35 genera and 145 non-extinct species. Chris relies on the groundbreaking DNA study by Sorenson and Payne (Robert B. Payne, The Cuckoos, Oxford, 2005) and a subsequent review of all cuckoo taxonomies (Johannes Erritzøe et al., Cuckoos of the World, London, 2012) for her count of 144 species in 38 genera. Extinct species are the St. Helena Cuckoo (in its own genus) and the Snail-eating Coua.

** A good source for this material is one of my favorite books, Mark Cocker’s Birds and People (Trafalgar Square Publishing, 2013), cited as one of Chris’s sources

Cuckoo by Cynthia Chris

Reaktion Books (U.K) & distributed by Univ. of Chicago Press in U.S.

August 2024 (Reaktion) & Oct. 2024 (Univ. of Chicago Press); also available in eBook & PDF formats

ISBN 9781789149319

paperback; 168 pages; 96 illustrations, 82 in colour

Gotta love cuckoos? Not if you are a reedwarbler! Great review – another addition to the Christmas list…